I write books for a living, but it took a dog to teach me what living was all about.

In the end she taught me about dying too, and how to let go of something you couldn’t imagine going on without.

Her name was Trixie and my wife, Gerda, and I would never be the same after she came into our lives.

Trixie was an inspiration. She restored our sense of wonder. She made us laugh and at times made us weep in anguish.

For me as a novelist she was a revelation, encouraging me to take a new, risky, challenging direction in my writing. She was a beautiful golden retriever, trained as a service dog, but she was also a sort of angel.

She’d been with us less than nine years, but that Friday morning when she refused food for the first time in her life, declining to take a single bite of an apple-cinnamon rice cake, one of her favorite things, I knew it was an ominous sign.

I rushed her to the vet who took an ultrasound and discovered a tumor on her spleen. “It could burst at any time,” he said. “You have to get her to surgery right away.”

In the large waiting room of the specialty hospital, Gerda and I sat side by side, sometimes holding hands, anchoring each other in the shallow optimism that circumstances allowed. Between us, we demolished a box of Kleenex.

We never had children. Gerda and I had been together every day, virtually all day, in our 32 years of marriage. She managed our finances, did book research and relieved me of all the demands that kept my fingers away from the keyboard.

We had always promised each other that we would get a dog, but we knew that a dog requires almost as much time as a child. And because of our work schedules—60 hours a week, sometimes 70—we hesitated to take the plunge.

We were supporters of Canine Companions for Independence, an organization that raises and trains assistance dogs, and they had encouraged us to adopt. Finally one evening I said to Gerda, “We’ll be ninety and too busy. We should just do it and make it work.”

Trixie had taken early retirement due to elbow surgery. Joint surgery will force the retirement of any assistance dog because, in a pinch, it might need to pull its partner’s wheelchair.

When Trixie met us, she was a highly educated and refined young lady of three. We were standing with others, but she came right to us, tail swishing, as if she had been shown photographs of us and knew we were to be her new mom and dad.

It was love at first sight.

She had a good broad face, dark eyes and a black nose without mottling. Her head and neck flowed perfectly into a strong level topline and her carriage was regal.

Beauty, however, took second place to her personality. Well-behaved, with a gentle and affectionate temperament, she had about her a certain cockiness as well.

In a picture of her CCI class, 11 of the dogs sit erect in stately poses, chests out, heads raised, each holding the end of its leash in its mouth. The twelfth dog sits with legs akimbo, grinning, head cocked, a comic portrait of a clownish canine ready for fun. Did I say refined? Not totally.

At first Trixie accepted the work schedule that Gerda and I maintained, which kept us at our desks until at least six o’clock, often until seven or later. Soon, however, Trixie decided that we were insane, and she set out upon a campaign.

One day, promptly at five, she came to the farther side of my U-shaped desk and issued not a bark but a soft woof. After telling Trixie that it was not yet quitting time and that she must be patient, I turned my attention back to the keyboard.

Fifteen minutes later, she issued another sotto voce woof. This time her head was poked around the corner of the desk, peering at me. Again, I told her the time to quit had not arrived.

At five thirty, she came directly to my chair. When I didn’t acknowledge her, she inserted her head under the arm of the chair, staring up at me with a forlorn expression that I couldn’t ignore.

Within two weeks we regularly knocked off work at five thirty, and within a month, because of the clock in Trixie’s head and her diligent insistence, five o’clock became the official end of the workday in Koontzland.

Those extra hours passed in a blizzard of tennis balls. I would throw and Trixie would retrieve until either I had no more strength or she dropped from exhaustion.

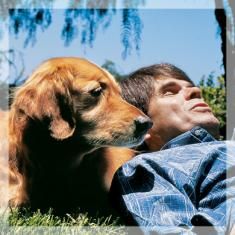

The shimmer and flash of her golden coat in the sun, the speed with which she pursued her prey, the accuracy of every leap to catch the airborne prize…she was not just graceful in a physical sense.

The more I watched her, the more she seemed to be an embodiment of that greatest of all graces we now and then glimpse, from which we intuitively infer the hand of God.

Then there was the “Lassie Incident.” One Saturday Gerda and I were working in our adjacent offices, she on bookkeeping, I on a novel with an approaching deadline.

As quitting hour drew near, we agreed on pizza for dinner. Gerda went to the kitchen to preheat the oven, then returned to her office to finish her data entries. About 15 minutes later, having approached my desk without making a sound, Trixie let out a tremendous bark.

I shot from my chair as if it were a cannon. I responded to Trixie with a command I had used only once before, “Quiet.” She padded away. From Gerda’s office came a window-rattling bark. I heard Gerda say, “Quiet, Miss Trixie. You scared me.”

Returning to my work space, she launched me from my chair again with two furious barks. Her raised ears, flared nostrils and body language indicated that she had urgent news to convey.

Feeling as if I were Lassie’s dad and Timmy had fallen down an abandoned well, I said, “What is it, girl? Show me what’s wrong.”

She hurried out of the room, and I followed her. Trixie trotted along the hallway, glancing back. Halfway across the living room, I detected the faint acrid scent of something burning.

Running now, Trixie barked one more time. In the kitchen, tentacles of thin gray smoke slithered out of the vent holes below the oven door. Peering in, I saw an object afire.

For a moment, I couldn’t identify the thing, and then I saw that it was a burning hand, standing on the stump of its wrist. I half-expected the burning hand to wave—but then I realized that it was not a hand after all. An oven mitt had been left in the Thermador. That night we gave Trixie extra treats.

I found the innocence of her soul to be a revelation. She didn’t need a new sports car or a week in Hawaii to know joy. For her, bliss was a belly rub, a walk on a sunny day—or in the rain, for that matter—an extra cookie when it wasn’t expected, a cuddle, a soft word.

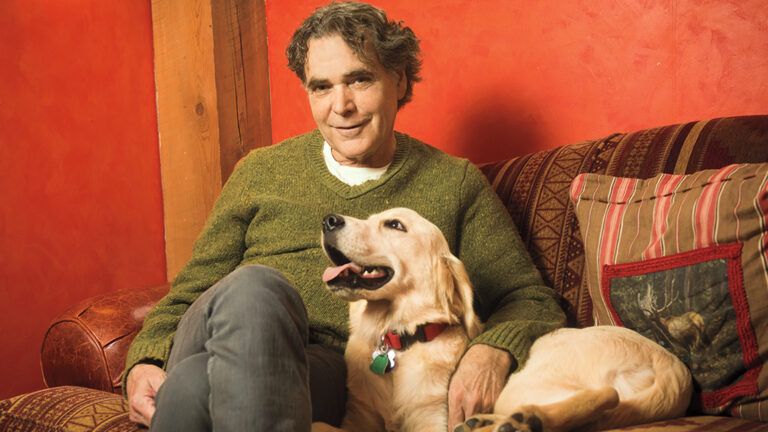

She lived to love and to receive love, which is the condition of angels. If Gerda and I had decided to delay adopting a dog or if we’d decided not ever to have a dog, I wonder who I would be. Whatever, I would not be the Dean Koontz I am now.

In our house we liked watching movies on a big-screen TV. Usually I sat on the floor so I could give Trixie a long tummy rub and ear scratch.

From time to time, Trix seemed to take an interest in the story. If she happened to be watching when a dog entered the frame she stood and wagged her tail. It was the image that attracted her, because she reacted even when no bark or doggy panting alerted her to a canine presence.

One evening, a character rolled into a scene in a wheelchair, which electrified Trixie. She stood and watched intently, and even approached the screen for a closer look. I’m sure she remembered a time when a person in a wheelchair needed her, and when she served ably.

The second novel I wrote after Trixie came to us was From the Corner of His Eye, a massive story, an allegory that had numerous braided themes worked out through the largest cast of characters I had dared to juggle in one book.

The day I started, Trixie curled up on her bed in my office and she watched me from the corner of her eye. The opening made a series of narrative promises that seemed impossible to fulfill.

The more I observed Trixie, however, the more confident I felt about being able to write this challenging book. The protagonists of Corner were people who suffered pain and terrible losses but who refused to give in to cynicism.

Because Trixie restored my sense of wonder to its childhood shine, I knew I had to write this story, a book that went on to sell more than six million copies worldwide and has generated tens of thousands of letters.

That night of Trixie’s surgery I never went to sleep, but spoke to God for hours. At first I asked him to give Trixie just two more good years.

But then I realized that I was praying for something that I wanted. And so I acknowledged my selfishness and asked instead that, if she must leave us, we be given the strength to cope with our grief, because her perfect innocence and loyalty and gift for affection constituted an immeasurable loss. Even in my pain and confusion, Trixie helped to teach me how to pray.

Over a week later Trixie died at home on her favorite couch, on the covered terrace where she could breathe in all the good rich smells of grass and trees and roses.

As her mom cradled Trixie’s body and told her she was an angel, I held her sweet face in my hands and stared into her beautiful eyes, and, as always, she returned my gaze forthrightly.

I told her that she was the sweetest dog in the world, that her mom and I were so very proud of her, that we loved her as desperately as

anyone might love his own child, that she was a gift from God.

And she fell asleep, not forever but just for the moment between the death of her body and the awakening of her spirit in the radiance of grace where she belonged, like an angel.