It hit me when I was only a kid in fifth grade.

I sat in our big Atlanta church one Sunday, listening to our preacher talk about a miracle Jesus performed, and it struck me that Jesus was always healing the sick.

In fact, that was one of the most important things he did! Right there in the pew, I thumbed through my Bible and started counting. “Do you know that over a third of gospels are about health?” I told my mom at Sunday dinner. “And in the book of Acts, I found nineteen examples of healing by Christ’s followers.”

“Hmm,” Mom said.

“That’s really a lot,” I said. Why didn’t we do more for the sick at our Methodist church? We put people on the prayer list or our pastor would visit them in the hospital. Maybe Mom or another one of the ladies would make a casserole. That was it. We helped and we cared but we didn’t necessarily heal.

I couldn’t get it out of my mind. I admit, I was a precocious nine-year-old, the first one to raise his hand in Sunday school, the one who had endless questions for our pastor. One day, maybe just to shut me up, he said, “Son, you’ll make a great preacher someday.” Would I? Was that what I really wanted to do? Run a church and give all those sermons? I didn’t think I’d be any good at it. What I fixed on was all this healing Jesus did.

“I’m going to be a doctor,” I said to our pastor the next time he brought up that minister idea. I was a good student and I figured in college I’d take all the premed classes and go from there. I’d driven by enough hospitals founded by Methodists like us or Presbyterians or Catholic religious orders, but as far as I could tell they had doctors and nurses and technicians, certainly more M.D.s than M. Divs. The best way to be a healer like Jesus would be to study medicine.

One semester of organic chemistry at the University of Virginia did me in. I was miserable. It wasn’t the subject that was the problem—I found it interesting enough. It was being with all those other premed students who were so competitive they hardly seemed to care about why they were learning what they were learning. All they wanted was to get top grades.

“Forget it,” I said. Senior year I was looking at seminaries, not med schools.

And yet, that fascination with health and faith, with both the body and soul and how Jesus healed the sick, hadn’t left me. When I applied to seminary, I asked, “What do you do to train your students to help the sick?” Yale Divinity School sent back a 10-page treatise on what they did to integrate faith and health in their curriculum. I was impressed. Fortunately I got in and headed north to New Haven, Connecticut.

Several very important things happened to me at Yale. First, I met a man named Sidney Tillery. As part of a seminar on counseling the chronically ill I was assigned to visit Sidney once a week. He was a patient at the VA hospital. He had a crippling vascular disease and I arrived with a slew of questions. Where did he feel the pain? On a scale of one to 10, how bad was it? What was it like eating, sitting, sleeping? At the end of the interview he asked, “Want to play cribbage?”

“I’ve never played before.”

“I’ll teach you,” he said. That was the start of our friendship.

Sidney was a World War II vet, a sturdy New Englander who’d raised a family and worked as a mechanic at the Electric Boat Corporation, which built submarines for the Navy. In another era, he’d have taken to sea as a whaler. Without any self-pity he talked about how much he missed being with his family or seeing his buddies.

Week after week we played cribbage and I gave up the prescribed list of questions. I learned how to listen. I saw how a chronic illness did its most crippling damage to the spirit. “Your patients will become your teachers,” our professor had said. Sidney Tillery taught me how to reach beyond someone’s aches and pains to minister to their soul. Jesus’ healing mission came alive to me over the cribbage board.

At the time, I was doing research on John Wesley, the eighteenth-century founder of Methodism. I kept coming across examples of how he, too, was concerned about his followers’ health. He tried out different homespun remedies and eventually compiled them in a medical text, The Primitive Physick, that would almost rival the Bible in popularity. Some of its advice might seem comical today, like the 18 cures for baldness (one look at me and you’d know they didn’t work), but the evidence was there that the church used to be directly involved in health care. Why weren’t we today?

Then one day in the chaplain’s office at Yale I came across a pamphlet called “How to Start a Church-Based Health Clinic.” The writer, Dr. Granger Westberg, explained how a congregation could sponsor a health clinic to minister to the poor and how he’d actually done it.

I called and talked to him. I went to Chicago to meet him. He introduced me to others who’d done similar work, in particular Dr. Janelle Goetcheus at the Church of the Saviour in Washington, D.C. After a visit with her, a light went off in my head: This is what I want to do with my life. This is what I’ve been looking for all along. I’d start a church-based clinic for the poor. We’d use the best that modern medicine had to offer and the spiritual tools Christ gave us. I’d be both minister and doctor.

I picked up the premed classes I needed at Yale—with the seminary’s encouragement and support—and went off to med school. I did my residency, all the while looking for the right place to start a church-based clinic. Someone pointed out that Memphis had the poorest population of any big American city. Didn’t Jesus go where the need was greatest? I didn’t know anybody in Memphis, but that was where I was headed.

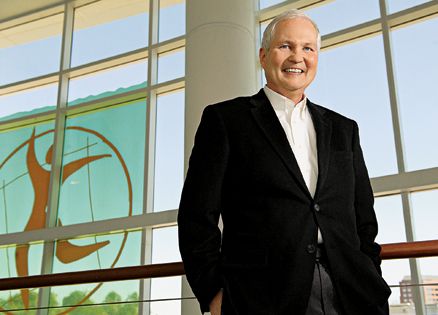

I joined the staff of St. John’s United Methodist Church there as an associate pastor and laid out my vision. For a year I talked to people. I asked Dr. Goetcheus so many questions that she finally flew to Memphis and told me face-to-face to stop calling her. “You know all you need to know,” she said. “What you don’t know, God will show you.” We opened the Church Health Center in a crumbling old house across the street from St. John’s with just one nurse and me. We saw 12 patients that first day.

That was 25 years ago. Today we have a staff of 220. Some 55,000 people depend on us for their health care. There is always a lot of work to do, but I have never forgotten the lesson I learned from Sidney Tillery and our cribbage games. I still see patients regularly. I do all I can as a doctor to address their aches and pains. Then we talk about their lives.

Most of them are the poorest of the poor. They have worked hard their whole lives, tough manual labor. Often their families have broken up and they’ve seen more sorrow than you can imagine—drugs, violence, the scourge of poverty—but when I ask them how they are, they will say, “I’m blessed.”

Some of them bless me quite literally. They lay their hands on me and pray over me. They remind me that I’m not the healer. God is the healer and it is the duty of the church, with all the help of modern medicine, to participate in that work.

That was the calling I discovered when I was just a kid in the pew counting up the miracles in the Bible. Jesus cared about the sick and it was as though he told me, “You should too.”

I do.

Download your FREE ebook, The Power of Hope: 7 Inspirational Stories of People Rediscovering Faith, Hope and Love