Having spent my business career in Cincinnati—and being a fifth-generation Buckeye—I have a natural interest in Ohio history. The other day I picked up an article entitled “The Real Johnny Appleseed” and got the surprise of my life.

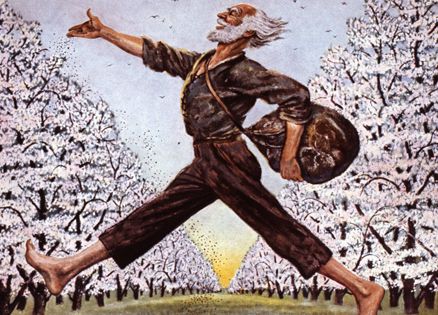

Like most people, I had accepted the story purveyed by Walt Disney and poets such as Vachel Lindsay, picturing Johnny as a wandering frontiersman who scattered apple seeds from Ohio to California and did an occasional good deed for pioneers heading West. Johnny seemed mostly a romantic myth, like Paul Bunyan or Mike Fink.

Not so. The real Johnny Appleseed was a businessman—a good one. His life is rich in lessons for businesspeople who want to succeed by combining know-how with ideals. At times Johnny even mixed business with an earnest appeal to his customers to remember the importance of God in their lives.

I, John Chapman, (by occupation a gatherer and planter of apple seeds)—that is how he described himself in 1828, when he was selling a town lot in the center of Mount Vernon, Ohio.

He was born in Leominster, Massachusetts, on September 26, 1774, and left home in 1797 at the age of 23, heading west in search of land and opportunity. Eyewitnesses described him as standing about five feet nine inches tall, with a stocky, vigorous frame.

John Chapman adapted well to the lonely, dangerous life of the western wilderness along the Ohio border, exploring the rivers and creeks in dugout canoes.

He planted his first apple trees in western Pennsylvania, not because of some attachment to that particular fruit, but because it was the quickest and easiest way to prove that he was cultivating land on which he had staked a claim.

When the frontier moved into Ohio, he moved with it, and at first followed the same pattern, planting trees on land that he hoped to farm. But at some point in those early years, Chapman realized that apple trees could be made into a business that would serve a vital need and suit his own skills as a frontiersman.

Today we have forgotten the importance of the apple to pioneer farmers. It was one of the few year-round foods. Apples were buried in late autumn before the ground froze, and dug out every week or two during the winter and spring. They were sliced and dried to be used in pies and cakes, side dishes and sauces.

Apple butter could be kept for months without spoiling, and was a necessity in every pioneer kitchen. Even more important was cider, which was a money-maker, with guaranteed sales to the nation’s growing cities.

For the pioneer, the problem was where to find decent apple trees.

The apple is a strange plant. It is not native to North America. It does not reproduce true from seed. Instead, almost every seed produces a new variety of apple, often inferior to the one from which it came. Apple trees can be improved only by grafting and through other skilled forms of nursery care.

There was no room for apple trees in the crowded wagons in which most families moved west. But John Chapman saw that if he preceded the frontier by a year or two, planting seeds and starting nurseries at strategic points, the farmers would have trees ready for grafting and cultivating.

From the beginning, Chapman was a well-organized, extremely hardworking businessman. He sold his trees to arriving settlers for fippenny bit each, about six-and-a-half cents. This was not a bad price at a time when land was selling for two dollars an acre.

Working alone, he transported hundreds of thousands of apple seeds he had collected from cider presses in western Pennsylvania. Traveling along the rivers in a canoe, he usually ended his 200- or 300-mile journey lugging the seeds on his back through the forest that covered almost every foot of Ohio.

The woods swarmed with wolves, bears and wildcats. Often Chapman met Indians in the forest. He soon realized he had nothing to fear from them as long as they were not on the warpath. He won their respect, and they taught him how to survive in the woods when food ran short—the wilderness traveler’s biggest worry.

Although he never married, John Chapman had a strong sense of home and family. He persuaded his father and stepmother to move to Ohio with their 10 children and made their home his base of operations.

During the War of 1812 Ohio was invaded by English troops and Indians from Canada. John Chapman volunteered to serve as a scout, prowling the forest in search of war parties.

Once he was spotted and pursued for miles by 17 Indians. He escaped by plunging into Lake Erie and breathing through a reed. Again and again he played Paul Revere, warning settlements of oncoming raids in time for farm families to flee to the safety of nearby forts.

When peace was restored, John Chapman resumed expanding his chain of nurseries. Eventually he supplied seedlings to 100,000 square miles of farmland.

In 1819 a Frenchman who visited Ohio remarked that “under every tree were large apples, so thick that at every step you must tread upon them, while the boughs above are breaking down with their overladen weight.”

Chapman’s nurseries were a forerunner of the chain store. It was all the more remarkable in an era with no decent roads and only primitive communications—there were just a few scattered post offices. Chapman’s business depended on his reputation for honesty and a quality product.

Today, running a company with factories around the United States and Canada, I find myself emphasizing these basic ideas that Chapman pioneered so many years ago.

The war’s bloodshed made John Chapman a religious man. He became a follower of the Swedish Christian theologian Emanuel Swedenborg. Chapman began to carry Swedenborg’s books and would read from them to farm families he visited. He called it news from heaven.

Hospitality was a strong tradition on the frontier. Some people would send their youngsters to bed hungry rather than deny a visitor a meal. Yet Chapman refused to accept any food until he saw that the children had been fed first.

Sixteen-year-old David Hunter of Green Township, Ohio, never forgot an encounter with Chapman in the early 1820s. His parents had died, leaving him with the responsibility of raising eight brothers and sisters. The young man poured out his woes to Chapman. “Have you planted any apple trees yet?” he asked.

Hunter shook his head. “I don’t have the money.”

“Take your wagon tomorrow and go down to my nursery at the big bend of the Rocky Fork. Tell my brother-in-law Bill Broom you have an order from me for sixty trees.”

“I can’t pay—”

“You’ll pay me when you can. This year, next year.”

David Hunter went home filled with new hope. The Hunter orchards flourished, the family prospered.

Chapman operated his business on trust. A handshake and a promise to pay were good enough for him. He collected most of his debts in a reasonable length of time, enabling him to keep expanding his nurseries.

His method was an early version of the installment plan, made popular in Ohio about 100 years later for the sale of pianos from the company founded by a music teacher and devout Presbyterian, Dwight Hamilton Baldwin.

Recently I negotiated a contract with a huge Japanese company. As we signed the documents our lawyers had prepared, the CEO remarked: “I suppose these legal forms are necessary, but in business the fundamental thing is trust.” I thought of John Chapman and nodded in agreement.

As he grew older, Chapman gradually became indifferent to making money. He earned enough to support himself. The rest he was inclined to give away.

Once he gave $50 to a stranded family, which enabled them to buy 100 acres of land. Often he would “accidentally” allow five dollars to fall out of his pocket, letting his hosts find it like manna from heaven after he was gone.

John Chapman extended his sense of caring to animals. On the long trip west, horses often broke down. The pioneers usually had no alternative but to turn them into the woods, where they eventually starved to death.

Chapman regularly rounded up such horses and fed them through the winter months. In the spring he would find new homes for them, giving them away to anyone who would promise them decent care.

In his later years, Chapman often invited the sons of the pioneers to join him in a forest camp, where they learned to share his sense of harmony with nature. They lost their fear of howling wolves and screeching owls in the night.

The youngsters also got used to John Chapman’s simple diet, which was largely potatoes, cornmeal, forest nuts and berries. Like Henry Thoreau at Walden Pond and John Muir, the creator of Yosemite and other national parks, Chapman liked to stress how little we really need to stay healthy and happy.

As he neared his 71st birthday, Chapman heard that one of his nurseries on the St. Joseph River had been damaged by wandering cattle. He set out to repair the fences, ignoring cold, snowy March weather.

He reached the cabin of William Worth, near Fort Wayne, Indiana, exhausted and sick, and died of pneumonia two days later on March 18.

A few weeks after, apple blossoms whitened on the millions of trees born from John Chapman’s nurseries. It was almost inevitable that he became a legend. Even before his death, people called him Johnny Appleseed. But businessman John Chapman deserves to be remembered for more than his apple trees. His enterprising spirit, his devotion to God, his reverence for nature, and his generosity are spiritual seeds that a modern businessman can plant. Who knows what remarkable things may grow from them?

View our slideshow of historic Johnny Appleseed images.