I admit, when it comes to Christmas, I can be a bit of a curmudgeon. Okay, maybe more than a bit. I can’t stand the rampant commercialization of the holiday. The forced good cheer. The profligate gift-giving.

I know Christmas brings joy to many. But I also know it leaves others feeling sad and lonely. Every year I wonder the same thing: How did the celebration of Jesus’ birth get wound up with all this other stuff? Why does God seem so far away to me at Christmas?

Last December I was deep into my annual holiday funk when it came time for our family to attend a Christmas play. Actually, I’d been looking forward to this particular play. It was called La Pastorela, or The Shepherds’ Play.

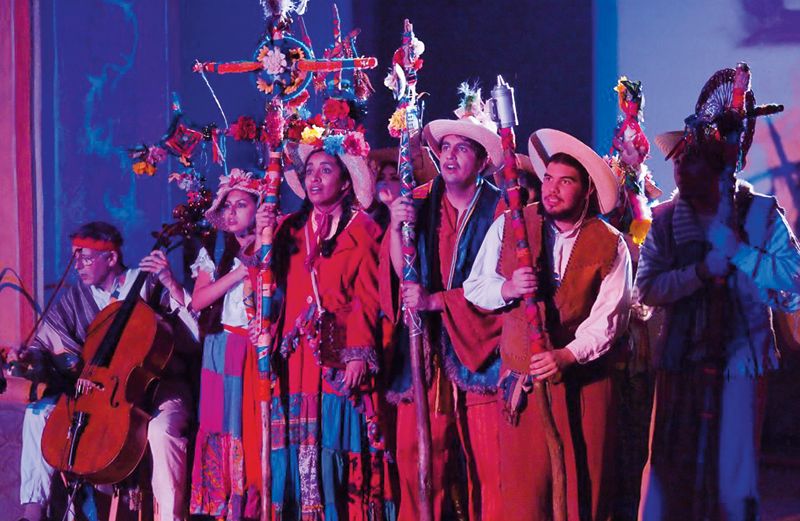

It was a restaging by a Central California bilingual theater troupe of an ancient medieval mystery play about the journey of the shepherds to Bethlehem to see the newborn Christ child. Don’t let those words medieval mystery play fool you. This was no staged history lesson.

The theater troupe, called El Teatro Campesino (Peasant Theater), had been putting on modernized versions of ancient Christmas plays for decades, every year playing to audiences of mostly migrant farm workers from the nearby fields.

The troupe got its start during the United Farm Workers’ strike in 1965, when grape pickers in California’s Central Valley walked off the job to protest low wages and harsh working conditions. A few of the farm workers staged plays to keep strikers’ spirits up. A theater troupe was born.

La Pastorela seemed like a respite from the craziness of American-style Christmas. Teatro Campesino’s holiday performances take place inside the beautiful eighteenth-century sanctuary of Mission San Juan Bautista, one of California’s 21 missions founded by Spanish Franciscan priests.

The mission is still a working Catholic parish. It’s a holy place, with candlelit chapels and a simple main altar backed by statues of saints (including John the Baptist, the mission’s patron saint). No Black Friday sales here.

On a crisp December afternoon we drove south from our home in San Jose, past the sprawl of Silicon Valley and into California farm country. Less than an hour later we were finding a place to park in the tiny town of San Juan Bautista.

Our kids, Frances (age six) and Benjamin (three), were excited, especially because they knew we’d go out to dinner after the play. My wife, Kate, was glad I was in a good mood.

She’s a priest at an Episcopal church. On top of my annual holiday gripes, I also dread the stress and frenzy of Christmas service preparations. For now, walking toward the mission along streets dotted with historic adobe buildings, I was content to make a truce with Christmas. This was more like it.

We waited in line, then filed into the brightly lit sanctuary. The crowd was a diverse group. Sophisticated theater lovers from San Francisco sat beside lettuce pickers in their Sunday best. A bus parked outside had brought students from a high school in East Palo Alto, one of Silicon Valley’s poorest cities.

Everyone looked excited. For many, especially the local farm workers, Teatro Campesino performances are a Christmas ritual. The plays are staged in Spanish. But the troupe includes an English-language summary with the program. And the story is so well performed, anyone can follow along.

The lights dimmed. Benji grabbed my arm and pressed against me. “Daddy, are there monsters in this play?” he asked anxiously.

“No,” I said. “But there might be some devils who try to stop the shepherds from seeing Baby Jesus. Don’t worry. They’re not real. Just actors wearing costumes.” Benji scanned the sanctuary. Seeing no devils, he relaxed a little.

The play began. A group of not-too-bright-looking shepherds bumbled to the center of the sanctuary, where the pews had been arranged to face a raised stage.

Suddenly a spotlight shone on a figure in white standing at the altar. An angel, announcing to the shepherds that the savior of the world had been born in a manger in the city of Bethlehem. The angel told the shepherds to journey to Bethlehem to greet the newborn.

A shiver went down my back. Already the shepherds were comically misinterpreting the angel’s instructions and arguing over which direction to walk.

Like their medieval forebears, Teatro Campesino’s plays keep audience members of all backgrounds engaged with the story by mixing a steady stream of humor with the religious themes. I laughed with everyone else at the shepherds’ antics.

But I kept thinking about that brightly lit angel at the altar and its words to the shepherds: “A savior has been born in Bethlehem.” I looked down at Benji. He was transfixed. He couldn’t possibly understand the dialogue. Yet something in the play was quieting his normally fidgety self. I too felt quiet inside.

The devils arrived. They were mostly local schoolchildren dressed up in Halloween-like costumes, running around the stage trying to scare the shepherds away from their destination. A grown-up devil tried various temptations—beautiful women, riches, alcohol—to lure the shepherds off track.

Each time, angels swooped in to save them. Frances and Benji cringed at the devils and clapped when the angels rode to the rescue. I clapped too. Everyone in the audience could see Joseph and Mary cradling the Baby Jesus at the altar just a few dozen yards from where the shepherds wandered.

They were so close to God, and yet so far. Just like I felt sometimes.

At last the shepherds were almost to Bethlehem. The devils seemed to have run out of temptations.

All of a sudden, at the back of the church, there was a bang. Smoke poured from the main sanctuary doors opposite the altar. The light turned ghastly red. A terrifying voice boomed out and a dark, imposing figure appeared in the smoke.

It was Lucifer, riding a black steed (actually, actors in costume) toward the shepherds, who froze, petrified.

Lucifer dismounted and strode to the stage, carrying a huge wooden cross. To my astonishment, he set the cross upright on the stage, hoisted himself onto it and hung there like Christ himself.

He glared down. Then he told the shepherds with triumph that this so-called savior they were journeying to see was nobody special. “I am showing you right now what is going to happen to this pitiful Jesus,” Lucifer said, sneering.

“He is not going to save the world. He is not going to triumph over anything. He is going to end his life hanging on a cross like a common criminal.”

In his deep, terrible voice, Lucifer sang the shepherds a song: “Ay Jesús, solo Jesús/ Quiso morir en la cruz./Su dolorosa pasión, sí señor/Contempla y llora, dijeron.” (“Oh Jesus, Jesus alone wished to die on the cross. Yes, my friend, consider his pitiful death and weep.”)

The song ended and the mission sanctuary became utterly silent. Kate and I were silent. The kids were silent. Lucifer climbed down from the cross and carried it off the stage. The shepherds, defeated, began to follow him.

They knew he was right. Jesus would die on a cross. Everyone in the church, actors and audience alike, seemed weighed down by unbearable heaviness.

Then the light blazed forth again on the altar, and there stood Archangel Michael with his angelic army. The angels charged forward, routing the devils. The red light disappeared. The sanctuary grew loud and bright. The devils fled and the smoke evaporated.

The shepherds, blinking as if awakening from a bad dream, turned around and hurried toward the altar, where Mary and Joseph waited patiently—as they had waited all along—for the world to recognize the precious gift they bore.

It was a happy ending. I could see the looks of relief on Frances’ and Benji’s faces. I stood and applauded with everyone else as the actors took their bows. But I was still thinking about that astonishing moment when Lucifer climbed onto the cross like Jesus himself.

Though I had been a Christian for many years, I had never seen a person hanging from an actual cross like that. I’d seen countless paintings of the crucifixion. But never the real thing. And the real thing, I now understood, was horrifying, overwhelming.

This really happened, I kept thinking. Jesus really did that. He really suffered like that.

I remembered something I had learned in my high school art history class. In the Middle Ages, when the Pastorela was first written, many people were illiterate. The church devised various non-written ways to communicate the basics of the faith.

Stained-glass windows and carvings in churches were one way. The Eucharistic liturgy was another. Then there were the mystery plays, reenactments of Bible stories usually staged by everyday people. Just like Teatro Campesino, with its origins in migrant farm workers’ struggle for fairness and dignity.

These non-written ways of preaching were successful because at its heart Christianity is an incarnational faith. Jesus, the Son of God, was a real person, not some transcendent deity out there in the ether.

He was born like everyone else. He ate and slept. And he died on the cross. People who witnessed that death felt just like I felt all these centuries later watching it reenacted onstage.

We filed out of the sanctuary past the actors, who were now standing beside the doors smiling and shaking hands with the audience. At that moment—maybe for the rest of my life—my hostility to Christmas was gone.

I still resist the commercialization of it all. But the reality of Christmas—the reality I had seen, heard and felt in that mission sanctuary—overwhelmed the world’s best efforts to dilute it.

Our savior was born on this night. Born just like you and me to save people like you and me. Nothing could stop me from celebrating that.

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith