Improvise, adapt and overcome. That’s what Marines do. That’s what I learned serving as a machine gunner in Iraq. That’s what I had to learn all over again when I came home.

I’d been in the Marine Corps Reserves five years when my platoon was called to active duty in 2005. We were sent to Fallujah as part of security and stability operations after some of the bloodiest fighting of the war.

We didn’t know much about what we were getting into. We landed at an American air base. Rows and rows of ammo cans were laid out on the tarmac. We were given orders to fill the magazines in our M-16 rifles. That’s when we knew we were headed into some seriously dangerous territory.

Donate gift subscriptions to Guideposts Military Subscription Program

During the four-hour ride to Camp Fallujah we clutched our M-16s so tightly our hands went numb.

In Fallujah, the scorching desert air, heavy with the stench of burning garbage and raw sewage, stung our lungs. The unit we were replacing showed us around.

“Here’s where you’ll be patrolling,” the platoon leader said, his tone matter-of-fact. Then I noticed we’d rolled up to a spot where a Humvee had been hit by a roadside bomb. Lying there in the dust was a helmet. A soldier’s helmet.

A terrible feeling clutched at me. I’m never going to make it home. I thought about the smart and stunning woman I’d been dating. I’m never going to see Lisa again. I caught myself. Man up, Marine. This was no time to give in to fear. This was why I’d joined the Marines. To face my fear and beat it.

Experts say childhood trauma marks you for life. It can make you stronger, more resilient. It can also crush your spirit, make you angry and fearful. My stepdad was an alcoholic and addict.

I was very young the night a scream woke me up, a night that I will never forget. Groggily I opened my eyes. The bedroom I shared with my sisters was dark. What I saw knocked the sleep right out of me. My stepdad was hitting my younger sister. Whaling on her in a drunken rage.

She screamed again. I huddled in the darkness, too scared to move, to even shout for help. My mom finally pulled him off her. From that moment on, fear ruled me. Fear of the dark. Of confrontation. Of violence. Of my stepdad striking again.

I hated living in fear. i wanted to be free of it, to be tough like my grandfather, a Korean War vet, and my uncles, who’d all served in the military.

It wasn’t until my junior year of high school that I found an escape. The most unlikely of escapes, something I never could have imagined in my wildest dreams.

I got to be friends with a ballet dancer. She told me how hard her training was, how her feet would blister and bleed. “But it’s all worth it to dance onstage,” she said.

“Aren’t you scared to get up in front of people like that?” I asked.

“Not really,” she said. “To put feeling and movement together and have people respond…there’s nothing like it.”

I was intrigued. She invited me to her next performance. When my friend did her solo, I was mesmerized. Gliding across the floor on the tips of her toes, she looked like she was floating. So light. So free. So far from the kinds of things that dragged me down.

I knew my friends would rib me about it, but I had to try ballet for myself. The first time I stepped into dance shoes, stood at the barre and did a plié, everything else fell away–the troubles at home, the fear that haunted me–and I knew. This was what I was meant to do.

I majored in dance at the University of New Mexico. From there, I landed leading roles in ballets and musicals across the state. My ultimate goal was to join a full-time ballet company.

When I got a scholarship to a ballet conservatory in Connecticut, I thought, This is it! My chance to make my dream come true. The training was grueling, six days a week, and I loved every minute of it.

I had no problem scoring freelance gigs after graduation. I figured a full-time job with a ballet company was right around the corner.

Then, after one audition, a director told me flat out, “You’ll never make it as a full-time dancer. You’re good, just not good enough.” But dancing was all I knew how to do!

I kept going, taking freelance roles and auditioning for ballet companies. After two years, though, nothing panned out and I was afraid that that director was right, I’d never make it in ballet. Afraid all that fear I’d been running from would finally catch up to me.

I felt betrayed–by my dream, by whatever or whoever had led me to it. Fine, I thought. I’ll do something totally different. Something that will make people see me in a whole new way.

I enlisted. The Marines’ core values–honor, courage, commitment–spoke to me. Back then, in 2000, it was peacetime, and the recruiter steered me to the Reserves.

Like all recruits, I had to go through boot camp. Marine Corps training is intense and brutal, designed to weed out the weak. But ballet turned out to be surprisingly good prep. I was used to pushing myself and rose to the challenges at Parris Island.

I was assigned to the TOW Platoon, 23rd Marines, and told I’d be serving one weekend a month, plus two weeks every summer. That changed after 9/11.

My unit was sent to Camp Lejeune. Six months later, we were sent home, even though what all of us wanted was to be overseas, serving our country, putting our training to good use.

I got a job as a resident adviser in the boys’ dorm back at the conservatory. I met Lisa, a ballerina. She wowed me–she was smart, beautiful and amazingly talented. We started dating. Things were getting serious.

That’s when my unit was deployed to Fallujah. The area was home to some of the best-armed insurgents in Iraq. Our base came under heavy mortar fire. Every day we’d hear the deafening crack of explosives.

We never knew when a house might be booby-trapped, a sniper might pick off one of us or a roadside bomb might rip into our Humvee. We hunted for insurgents at night and took care of villagers during the day, passing out food, water and school supplies.

We Marines did what we were trained to do–improvise, adapt and overcome. There was a kind of choreography to our movements, whether it was screening locals coming on base, searching house to house or traveling by convoy.

We were in Fallujah an incredibly tense eight months. Every Marine in my platoon survived. That was some kind of miracle, like we’d been guided and protected somehow.

Lisa was there waiting when I got off the bus back home. I walked right into her arms. I was ready to build a life with her. To do that, I needed a steady job. I found one as a technical specialist at CULTEC, a storm-water management company.

I bought a condo. Six months in, I thought my transition to civilian life was going great.

Until Lisa sat me down one afternoon and said, “We need to talk.”

“Okay.”

“That’s just it,” she said. “You’re not okay, even though you think you are. You’re angry. Agitated. Depressed.”

I was about to protest. But then she said something that stopped me in my tracks. “Roman, people are afraid of you.” Lisa looked into my eyes. I thought of times on the freeway that someone cut me off. It was like I was back in Iraq, rumbling along in my Humvee.

If cars got too close, we’d run them off the road or fire warning shots. Here, I’d be filled with the urge to ram the other driver. Sometimes I had to pull over and call Lisa to talk me down.

Crowds got me keyed up too. I couldn’t stand not having personal space, so I made it a game to see how hard I could bump people. I’d slam my shoulder into them and watch them jump back, stunned…afraid.

I felt sick. All these years I’d been working to rise above my own fear. Turning into the kind of person who inspired fear–that wasn’t the way to do it.

“I just want you to be happy,” Lisa said. “If you could do anything in the world, what would you do?”

The answer flew out of me. “I’d start a dance company.” What made me say that? It couldn’t have been my brain talking. It had to have been my heart.

Lisa grabbed my hand. “Let’s do it!” she said.

And we did. We rented a rehearsal studio. Named our company Exit 12 Dance Company, for the freeway exit near us. Made a video of a dance we came up with and sent it to a director.

He rejected it, but gave me some constructive criticism: “A choreographer needs a vision. A message or something new. This doesn’t say anything.”

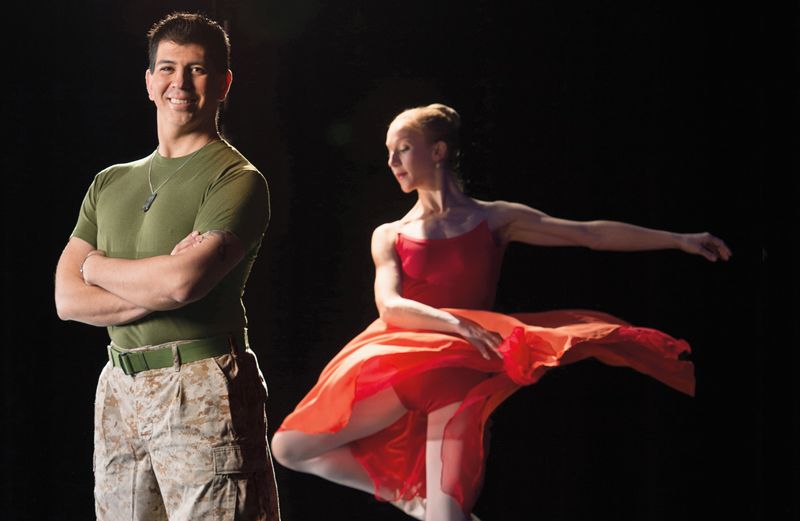

What did I have to say? All I knew was ballet…and the Marines. Could those two worlds come together? I wouldn’t know if I didn’t try. Improvise, adapt and overcome, right?

Lisa and I choreographed ballets inspired by my experiences in the military. Our first work, Habibi Hhaloua (Arabic for “My beautiful, you have my eyes,” a phrase the Iraqi people use to express love), was about a Marine in Iraq, thinking about what matters to him in life–home, courage, love, faith.

Our next piece was about the war’s effect on families. Another explored the relationship between the military and the Iraqi people.

Little by little, as I developed the dances and channeled my emotions into movement, my anger and anxiety melted away. And at last the fear that had animated so much of my life drained away too.

After one performance, a man came up to me backstage. “I served in Tikrit,” he said. “Thank you for telling people what it was like. It’s important.”

That’s when I knew. I’d been guided after all. I’m doing what I’m meant to do, being who I’m meant to be–ballet dancer, Marine, and husband and partner to Lisa. All of it fearlessly.

Bring faith and inspiration to our troops! To donate a Guideposts subscription now, click here.