I wanted the job more than anything in my life. I was a veteran, a grown man, ready to marry and settle down, but I couldn’t keep a job and I was discouraged, all because I stuttered.

I had worked as a strawberry picker, a house painter, and even a fireman for the Atlantic Coast Line Railroad. I lost that job because by the time I was able to call out the train signals ahead we were already four or five miles down the track.

Then I heard that a candy company in Plant City, Florida, was looking for a route driver. And I’d heard that the owner of the company, a man named Miller, was a former stutterer who had somehow learned to control his stutter.

A fellow sufferer, I was sure, would certainly understand and hire me. I set my heart on getting that job.

I got an appointment with Mr. Miller. When his secretary ushered me into his office, Mr. Miller, a kindly looking man who wore wire-rimmed glasses, looked me over. Then he asked why I wanted the job.

I couldn’t think of anything smart to say; I just started blurting the simple truth. “B-b-because I need the m-m-money,” I sputtered. I knew I sounded terrible, but I thought, Well, at least he’s hearing me at my worst.

For a long time, Mr. Miller didn’t say anything. Then finally he looked me straight in the eye. “Mr. Tillis,” he said softly, “I’m not going to give you a job.”

I stared at him, dumbfounded. He must have seen the surprise in my face.

“Oh, don’t get me wrong,” he said. “I think you’d do well. It’s just that I don’t have an opening right now.” Then he reached into a desk drawer and pulled out a piece of paper, worn and tattered. “I’d like you to take this home and read it,” he said. “Read it every night for a month.”

Hardly hearing his words, I reached out numbly, took the paper and stuck it in my pocket. Tears of disappointment burned my eyes. I turned my head away, told him good-bye and slumped out of the Miller Candy Company.

That night I felt totally dejected. “Who wants a stutterer around?” I asked myself in defeat. Nobody. And as long as I stuttered I would be a nobody. I had lived with this pain all my life.

I didn’t know that I talked differently until I started school. When I tried to talk everybody laughed. I began to withdraw more and more into myself.

My mother often said that God would help me solve my problem. I couldn’t see how. We were Baptists, but once a week Mama would take me up the road to a little Pentecostal church.

I loved to listen to the singing there, the guitars and the fiddles they used in those midweek services. And when I joined in the singing, I noticed that I didn’t stutter at all.

Mama would hold family songfests on the front porch every evening, all of us sitting around and singing for hours, I not stuttering on a word. We found out that when a stutterer speaks, air gets trapped in his throat. But when he sings, for some reason, the breathing apparatus works normally and there is no stutter.

I sometimes wondered if I might go through life singing, never having to talk again.

But after the interview with Mr. Miller, I was prepared never to utter another sound. I took the piece of paper he had given me out of my pocket, ready to tear it to shreds. But something made me look at it.

It was a prayer—a very well-known one, but one I didn’t know at the time: “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, the courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference.”

I read the words again. Then again. They were like the light at the end of a tunnel.

Accept the things I cannot change. I could work at easing my stuttering, I knew, but I probably could never really change the way I talked.

Courage to change the things I can. What I could do something about were all my fears—fear of stepping out of my shell, fear of trying to be somebody, fear of thinking bigger than I had been doing.

God, grant me the serenity. Here, I knew, was the key to the whole prayer. When, I wondered, was the last time I actually had reached out to God?

Years earlier, when I was a kid, I had prayed that I would wake up one morning and talk differently. When it didn’t happen, I forgot about God. But from what I was feeling now, I was pretty sure the Lord hadn’t forgotten about me.

Soon I was asleep—a deep and restful sleep. But though serenity came that night, it didn’t hang around all the time. And change didn’t come overnight either.

I kept reciting that prayer, reminding myself of its words and their meaning, till I finally could place myself in God’s hands, in trust, without fear of what might happen to me.

I gradually grew aware of a desire deep within me to write songs, the kind of country music songs we had sung in the Pentecostal church. I learned to play the guitar and started writing.

At the same time, I often thought of how enjoyable it would be to stand up in front of people and entertain them, but I knew this was a daydream because of my stutter.

Some months later, armed with some of my songs, I went to Nashville in hopes of getting somebody to listen to my work. One door led to another, and one day I got an appointment to audition for Minnie Pearl, one of the biggest names and greatest people in country music.

I was scared. As I went to the studio, I kept praying: “Your serenity, Lord. Your serenity.”

The audition went well and Minnie Pearl hired me as a backup musician and a songwriter. I was happy, but I stayed in the background for years and years, nowhere near my daydream of standing up and doing the entertaining myself, still frightened of what people would think of my Porky Pig stammer.

Then, in 1970, Glen Campbell invited me to be an accompanying musician on his Goodtime Hour television show. We used to kid around with one another, and one day backstage I found myself trading jokes with Glen and some of his guests.

“Hey, Mel,” Glen said, suddenly serious, “you’re funny, you know that?”

“Yeah,” I said, laughing, “really funny.”

But Glen wanted me to know he wasn’t kidding. “I’d like to use you on the show, have you introduce yourself in a skit.”

“No way!” I said.

I kept trying to back out, but Glen and a few others wouldn’t hear of it. They helped me to rehearse what I’d say to the audience, but I was so nervous that the few lines I practiced kept coming out as messed up as a two-headed calf.

The night before we were to tape the show, I called my wife, Doris, at our home in Tennessee. “I don’t know what I got myself into, honey,” I said, “but right now I feel like I want out.”

Before I knew it, a bunch of yelling broke out on the telephone, not just from Doris but from our four kids who were on other extensions. “Daddy, you better do it,” said my boy Mel Jr. “I told all my friends you were going to talk on television.”

I gulped. Then Doris, in her soothing way, said, “I hope you realize we’re all behind you. Don’t be afraid.”

Afraid. Yep, that’s what I was. When I hung up the phone, my mind went back to a scrap of paper. Its words by now were as clear in my memory as they must have been on that paper when Mr. Miller first wrote them. “God …,” I began silently.

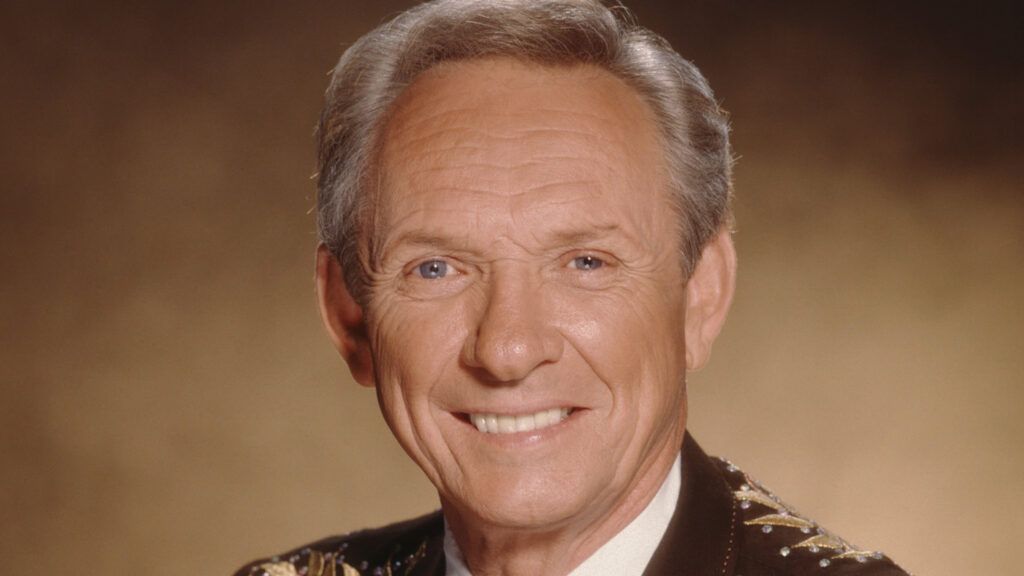

The next day, I went in to face the TV cameras. “The other d-d-day, somebody asked me when I was going to b-b-be on television,” I stuttered to the audience, trying to get out my introduction to my song. “I t-t-told them two years. I just w-w-wasn’t sure when I w-w-would ever finish th-th-this introduction.”

To my amazement, everybody laughed along with me. And my fear got drowned out in the laughter.

I could poke fun at myself, and people would respond—not in ridicule, but in warmth and fun. The audience would accept me, just as I was. And, more important, the prayer that Mr. Miller gave me had finally taught me to accept myself.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.