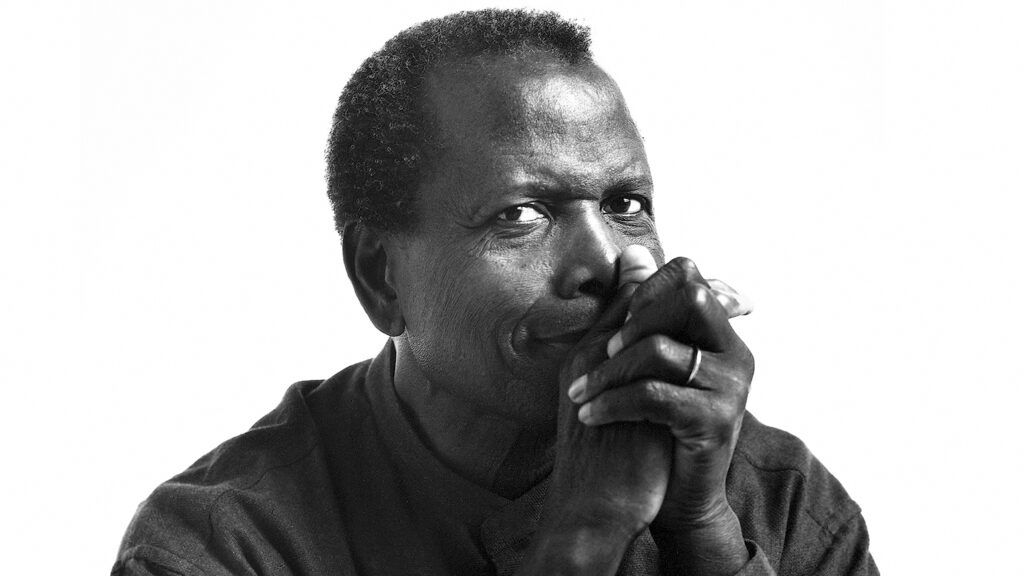

When I left the Bahamas and came to New York City as a teenager, I had no plans to be an actor. I just kind of stumbled into it because I needed work and was leafing through the want ads in the Amsterdam News one day.

The “Actors Wanted” page caught my eye and I thought, Why not? I’d already tried Dishwashers Wanted, Porters Wanted, Janitors Wanted, Drivers Wanted.

I tried out for the American Negro Theatre company and persevered to get an understudy job. One night the guy playing the lead role—a kid named Harry Belafonte—was absent, and I had to go on in his place.

It just so happened that night a casting director was in the audience. He got me a part in a Broadway production of Lysistrata. The play ran only four days, and though the critics hated it, they liked me.

I got another part as an understudy for a road show, then I was in two major feature films, No Way Out and Cry, the Beloved Country. But after that, nothing.

Meanwhile, I had married a beautiful girl named Juanita, little Beverly had come along and there was another baby on the way. I’d made three thousand dollars from the movies, but I had sent that back home to my parents in the Bahamas. With no work coming in, we were up against it.

So when a buddy of mine had got the idea of starting a rib joint, it seemed that we had nothing to lose. We scraped together enough to open Ribs in the Ruff. It was just another Harlem hole in the wall, eighty cents a meal, including side dishes.

My partner and I did everything. We cooked the ribs, made the potato salad and coleslaw, bussed tables and scrubbed the place down when we closed. Times were so tough right then I used to take milk home for the baby.

I was tapped out and feeling pretty worried one day, and there was nothing encouraging in sight. Out of the blue, a big-time agent by the name Marty Baum called. “Would you come down?” he asked. “I have something I want to talk to you about.”

He wasn’t my agent, of course. He was just helping out on a casting assignment. I went right over to see him.

“Go over to the Savoy Plaza Hotel,” he said. “There’s a gentleman who wants to see you about a part. Here’s the name.”

I could hardly believe my luck. I went over. Two guys were there, the producer and the director. “We would like you to read for us,” one of them said right away.

They gave me a script and a few moments to look over the scene. Then I read for them. I felt good about my delivery, but they didn’t say much about it.

Instead, they asked me about my life and what I had done in the business. Then they gave me a copy of the script to take with me and said that they’d be talking to Marty Baum.

I talked to Marty too. “Read the script,” he told me. “Call me tomorrow and we’ll work something out.”

I went straight home to my apartment at 127 Street and Seventh Avenue and read the script. I didn’t like it. The part they wanted me for was a janitor in a casino.

He was a very nice man, but there had been some kind of murder at the casino, and it was thought this janitor might have some information that could incriminate whoever was responsible. He received threats and warnings to keep his mouth shut, so he didn’t do anything, didn’t say anything.

Then, to prove they meant business, the bad guys killed his young daughter, throwing her body on his front lawn. He was enraged. He was tormented. Still, he remained passive. He didn’t do anything for himself. He just left it to other people to fight his battles for him.

READ MORE: MICHAEL LANDON ON DIVINE BLESSINGS

I thought long and hard after reading the script. Here was a chance at a role that might pay good money. But something else, more important than money, stuck in my mind. Memories of growing up back on Cat Island.

It was a wonderful place to live. We were poor, so even as a child, I had my jobs, my purpose, and I knew I had to contribute to the thin margin of our survival. As soon as I was big enough to lift a bucket, I carried water for my mother. I went out into the woods to gather bramble to make our cooking fire.

But I felt lucky. I knew how we’d all sit together on the porch at the end of each day, together, fanning smoke from the pot of burning green leaves to shoo away the mosquitoes and sand fleas. And every Sunday we would walk to the little Anglican church in Arthur’s Town to attend services.

Then we would walk home, all the kids with our shoes slung over our shoulders by the laces—not to be worn again for another week. Life was simple back then, and I was free to roam anywhere. I wasn’t a spoiled child, but I was bathed in love and attention.

When I was 10, we moved to Nassau, the capital of the Bahamas. My dad, Reggie, was 50. He was hardworking, but the only thing he knew how to do was tomato farming, and the soil in Nassau wasn’t good for that. Plus, by then he was suffering severely from rheumatoid arthritis.

The only way he could make a living was to have my brother in Miami send him boxes of very cheap cigars. He’d spend the day walking around town selling the cigars, one to this person, two to another. That’s how poor we were. But my dad did what he had to do.

My mom, Evelyn, always measured up too. She would go scouring the neighborhood and nearby woods, picking up rocks and stones—20-pound, 30-pound, sometimes even 50-pound stones. She’d gather them into a big mound of about 2,000 pounds in our front yard.

Then she would sit under an almond tree with a hammer in her hand and a big straw hat on her head. From early morning to night my mother would hammer those stones until they were gravel.

It would take her weeks, sometimes months, to break a pile of stones. When she had an impressive enough pyramid, a man would come by with his truck. They’d bargain, and he’d pay whatever price she was able to negotiate—fifteen shillings, if she was lucky, which was only about six dollars.

Then his workmen would come with his truck and shovel all the gravel into it and take it away. But the things that Reggie and Evelyn did for a living in no way articulated who they were as people. Everything they undertook was honorable, because that’s who they were.

When I got to New York, I was given the opportunity to do work that would reflect who I was. And who I was had everything to do with Reggie and Evelyn and each cigar sold and each rock broken.

That’s how I’d always looked at it. My work is who I am, and that work would never bring dishonor to my father’s name.

So I knew I couldn’t take the role. The character simply failed to measure up. He didn’t fight for what mattered to him most. He allowed himself to be dishonored.

First thing the next day I went back to Marty Baum’s office.

“How’d you like the script?” he asked.

“I have to tell you, I’m not going to play it.”

“What do you mean?” he asked, irritated.

“I can’t really tell you,” I said. “But there’s something about it. I just don’t want to go into it.”

READ MORE: DUKE ELLINGTON ON HIS PATH OF PRAYER

“That’s the way it goes,” he told me.

I thanked him and left. Then I went over to Fifty-seventh Street and Broadway, one flight up to a place called Household Finance Company, and I borrowed seventy-five dollars on the furniture in our apartment. Our second child was due soon, and I knew that was what the hospital was going to charge.

Six months later, Marty Baum called again. “What are you doing?” he asked.

“I’m still in the restaurant, working.”

“Come down. I want to talk to you.”

So I went down to the offices of Baum and Newborn, across from the Savoy Plaza Hotel. Marty sat me down.

“I don’t have a job for you,” he said. “But I wanted to say something to you.” He stared for a moment before continuing. “I’ve never met anybody like you. That was a good part, and you turned it down. You haven’t done anything since, and it would have been $750 a week, which is a nice piece of change.”

He asked again why I hadn’t taken the part. All I could say was, “It’s the way I am.”

Marty Baum shook his head and said, “Anybody as crazy as you, I want to handle him.”

That’s how I landed with a big agent, and how my career got on solid footing.

If I could tell Marty Baum now, maybe I’d say it’s all a matter of conviction. We all have to live with the consequences of sticking to our convictions. I walked away from $750 a week, but I also walked away with my self-respect.

If I had gone the other way, I might have ended up in a bright situation, but I know I would have felt something was missing. You see, I long ago learned that my work is me, and I try my hardest to take care of me, because I’m taking care of more than just the me one sees.

I’m also taking care of Evelyn and Reggie, the parents God blessed me with back in a special place in the Bahamas named Cat Island.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.