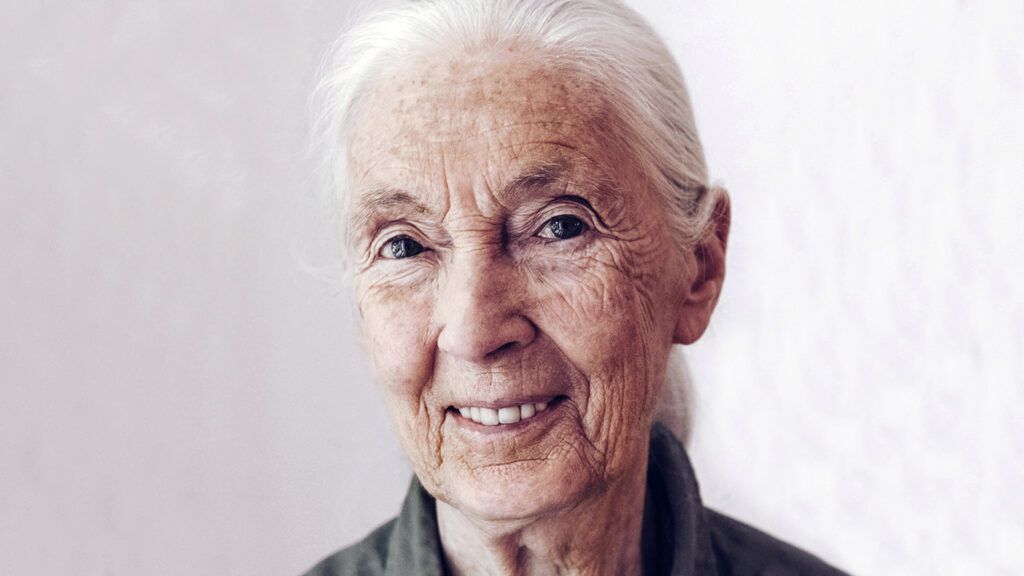

For more than 40 years, I have studied some of our closest relatives in the animal kingdom. Much of that time I lived among the chimpanzees of Gombe National Park in Tanzania, East Africa, observing them for hours, filling notebooks with accounts of their behavior.

More recently, alarmed by the harm we have inflicted on the natural world, I have turned my energies to the protection of wildlife and the environment.

I travel all over the globe in my efforts for conservation, and people often ask me: Having seen what we have done to this world and to the living things that share it, how can you keep doing the work you do?

It was a question I found myself thinking about when I returned to Gombe on July 14th, 2000, 40 years to the day after I arrived with my mother, Vanne, to begin my research.

I was there to celebrate the fortieth anniversary of the longest study of any group of animals anywhere. My mother had died just a few months before at age 94, so the memories that flooded into my mind were bittersweet—thoughts of days and people long gone.

From the earliest times, my mother nurtured my passion for animals. Instead of scolding when she found that I, at 18 months, had taken a handful of earthworms to bed, she quietly told me they would die without earth. I promptly gathered them up and toddled with them back into the garden.

Years later, when the authorities in Tanganyika (now Tanzania) refused to allow a young English girl to venture alone into the forests of Gombe to observe chimpanzees, it was Vanne who volunteered to accompany me.

On that anniversary day at Gombe last year, I climbed to the Peak, the outcropping of rock above Lake Tanganyika from where, armed with binoculars, I had made many of my early observations of chimpanzees.

From there I had first noticed an adult male, whom I named David Greybeard, pick leafy twigs and strip the leaves to fashion tools, which he then used to fish termites from their underground nests. I had learned—again from David Greybeard—that chimpanzees are hunters and that they share their kill.

I had been privileged to know some amazing chimp characters over the years … Olly, Mike, Mr. McGregor, each with his or her unique personality. I thought of the grand old matriarch, Flo, and her daughter Fifi, a tiny infant in 1960 and the one individual from those days still alive now.

Sitting up there, in that place of memories, I reflected on the plight of chimpanzees and other wild animals in Africa today. In 1960 there were forests fringing the 300-mile shoreline of Lake Tanganyika and extending for miles. Now cultivated fields surround the mere 30 square miles of Gombe National Park.

With the tree cover gone, every rainy season sees more of the precious topsoil washed away into the lake. Where there were once lush forests, many places today are desert-like. Not only have the animals gone—the humans are suffering. And this scenario is repeated again and again in the war-torn countries of Africa.

I understand why many of my fellow scientists believe we are spiraling toward global disaster. Still, I have reason for hope. And I collect and always keep with me on my travels symbols that express that hope.

My first reason for hope is the marvel of the human brain. Surely having conquered space and invented the Internet, we can find ways of living in greater harmony with nature.

Around Gombe we are currently working with people in 33 villages to improve their lives with tree nurseries, environmentally sustainable development, conservation education, primary health care, and AIDS awareness.

Science is inventing alternatives to fossil fuels; laws have been enacted to control dangerous emissions; timber companies are practicing responsible logging, and so on.

As a reminder of the ingenuity of the human brain, I carry with me a part of an eco-brick made from industrial waste. It is coated so that it will last 300 years or so, yet it is cheaper than an everyday building brick.

These eco-bricks can be used to build hospitals and schools in the developing world—and solve their waste-disposal problems at the same time.

My second reason for hope is nature’s amazing resilience. Polluted water can be cleaned; man-made deserts can bloom again. I carry a leaf from a tree that grows in Nagasaki, where the second atomic bomb was dropped at the end of World War II.

Scientists predicted that nothing would grow in the scorched, devastated area for at least 30 years—yet the plants came back quite quickly. One slender sapling did not die. Now it is a huge tree and every year puts out new leaves; it is one of these which I always keep with me.

Animals on the verge of extinction can be rescued. I have in my collection a feather from a California condor—a species reduced to only 14 individuals a few years ago. All were captured for breeding, and now there are 40 condors flying free in 4 different release sites.

I also have a feather from another species making a comeback against the odds, the peregrine falcon.

My third reason for hope is the indomitable human spirit—the people, all around us in all walks of life who tackle seemingly impossible tasks and never give up.

I carry a piece of limestone from the quarry on Robben Island where Nelson Mandela labored for 18 of his 27 years of imprisonment and yet emerged with so little bitterness that he could go on to lead his nation from the evil of apartheid into democracy.

And I have a wooden comb with a decoration of woven wool made and sold by a Tanzanian man who lost his fingers to leprosy but still found a way to make a living—weaving colored yarn with his stumps and his teeth.

I also have a surgical glove with a bent-in thumb, from the left hand of orthopedic surgeon Paul Klein. When he was only a six-year-old boy, an explosion all but destroyed his hands. Though his left thumb could not be saved, after hours of painful surgery, his fingers were reattached.

He decided he wanted to become a surgeon himself. “Impossible,” people said. Yet he persisted, and today Dr. Klein operates on children who have been injured in accidents.

My fourth and final reason for hope is the enthusiasm of young people once they know the problems facing the world and are empowered to act. To remind me of that, I carry a stuffed toy, a small spotted dog that five-year-old Amber Mary brought me, along with a plastic bag holding a few pennies, at the end of a talk I gave in Florida.

She had seen the National Geographic special where the little chimpanzee Flint dies of grief after losing his mother.

Little Amber Mary knew about grief; her brother, who had loved to watch the chimps at the zoo, had died of leukemia. Week after week, she had saved her allowance to buy the toy dog.

Would I give it, Amber asked, to one of the orphan chimps we were caring for, so that he might be less lonely? And, she added, with the leftover pennies, could I buy him some bananas?

I kept Amber Mary’s dog and her pennies to show others. When they see those pennies, people reach into their pockets for whatever they can give to help orphan chimps and other animals.

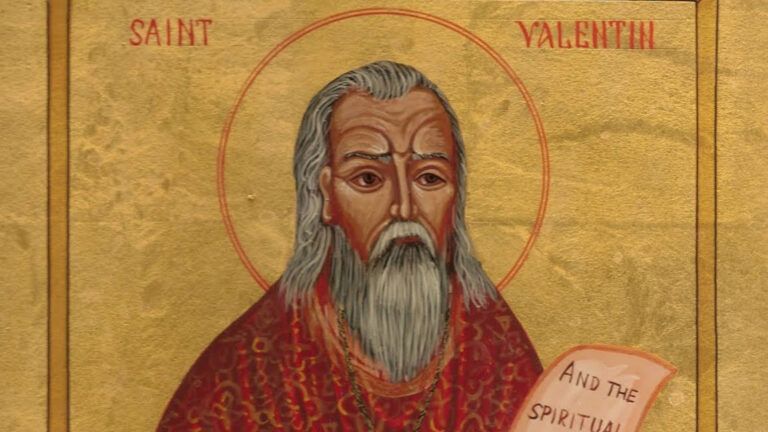

Sitting there on the Peak last July fourteenth, I remembered all my reasons for hope. As the sun sank lower in the hills on the other side of Lake Tanganyika, I climbed down to a waterfall that, for me, is a spiritual place.

Over the aeons, the falling water has carved a deep channel into the rocks. The roar of the water and the spray-laden wind created by the falls stimulate the chimpanzees to perform spectacular, rhythmic displays, swaying from foot to foot and hurling rocks into the streambed.

Could they perhaps be expressing their awe and wonder at the splendor of God’s creation?

The chimpanzees have taught us that we are not the only beings on this planet with personality, the ability to reason, and the capability for love, compassion and altruism as well as violence and cruelty.

But we humans are the only beings who have developed a sophisticated spoken language. With that gift, I believe, comes a responsibility: to act as stewards for God’s creation, this amazing planet.

Each one of us makes a difference every day of our lives, and we have a choice: What sort of difference do we want to make? There at the beautiful waterfall I felt utterly connected with that great power from which we draw our strength—God.

With the sun setting, I began to make my way from the waterfall to my house on the lakeshore. Later that evening I showed slides of the early days at Gombe with our Tanzanian staff. Afterwards, I took a walk along the pebbly beach. It was a full moon and once again, I felt keenly the privilege of being in such an unspoiled place.

I thought of my mother, Vanne, remembering her constant encouragement. She was always urging me to carry on, to share the message of hope with people around the world. “Without hope,” I could hear her saying, “what is the future for your three grandchildren, your two nephews? What is the future for all the world’s children?”

All I could do, sitting alone on the beach in the moonlight, was open my heart to the greater power of God. And I felt renewed, ready again to carry the message of hope, as I carry its symbols, for the beleaguered chimpanzees of Africa and for the children of the world.

I knew, as I sat there on the lakeshore, that hope for the future lies not in the hands of the politicians, the industrialists, or even the scientists, but in our hands. In yours and mine.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.