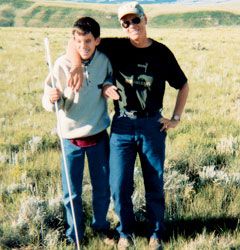

Mountains. I drew the line at climbing mountains. Everything else my son, Cody, had wanted to try—canoeing, hiking, skiing—I’d taken him. Not that I hadn’t been worried on those outings, trying to anticipate every problem we might encounter. But here in southwestern Montana, you pretty much live and breathe the great outdoors, and I didn’t want Cody to miss out just because he was blind.

Cody was born with an eye disorder called retinopathy of prematurity. By age two, he was completely blind. I got involved with the National Federation of the Blind (NFB) because I was desperate to help my son. Right away, I bought him a cane so he could learn to get around. And Cody was eager to explore the world. To him, blindness wasn’t a disability but simply a part of him. “So I can’t see,” he’d say matter-of-factly. “I’m not going to let it stop me.”

I shouldn’t have been surprised when he started asking about climbing. He was 12 then. Were there mountains nearby? What were their names? Which ones could be climbed? I told him our town, Dillon, lies in a valley surrounded by mountains. The Bitterroot range. The Pioneer Mountains—Torrey, Tweedy, Baldy. All of them can be climbed. I’d made it up many of those peaks myself.

“Dad, what does it feel like to stand on top of a mountain?” Cody asked.

“It’s like you’ve got the whole world spread out in front of you,” I said.

“I want to do that—climb a mountain and stand on top,” Cody declared.

“I’ll take you…” I said, “…someday.”

I left it vague. And I kept putting Cody off every time he mentioned mountain climbing. That went against everything I’d talked about with other NFB parents—we were all for our kids being active so they’d be ready to lead independent lives. But mountain climbing? That’s where I drew the line. I was afraid what might happen to my son high up on a peak, even with me guiding him. He could lose his footing on loose rock, tumble over drop-offs. I could see all the dangers Cody couldn’t. Wasn’t it my job as his father to protect him?

Cody kept at me. The spring my son was 14, Eric Weihenmayer became the first blind person to summit Mount Everest. Cody couldn’t have been more excited if he’d made the ascent himself.

Weihenmayer was the guest speaker at the NFB convention in Philadelphia that July. Half an hour before the talk, Cody was right up front, his tape recorder at the ready. Afterwards, he rushed to me. “Dad, you heard what he said. You don’t climb with your eyes, you climb with your hands and feet! Well, when are we going climbing?”

Cody wasn’t out to set records. He just wanted to experience the thrill of mountain climbing, like any teenager. I couldn’t deny my son that, not anymore. “When we get home,” I said, “we’ll climb Baldy Mountain.”

There was no going back on my promise. Still, doubts flooded my mind. I recalled the time Cody got distracted and ran smack into a brick pillar at school. He had to go to the hospital for stitches. Baldy isn’t Everest. You don’t need to cross ice fields or rappel down rock faces. But at 10,568 feet, it is a wild mountain. No groomed trails. You’ve got to make your own way to the top. One wrong step could spell disaster.

What if he slips and breaks something? What if I get hurt? How will Cody get down on his own? Was I putting my son at risk, being an irresponsible dad?

The morning of our climb, August 10, 2001, I tried to quash my doubts. We drove out to Baldy and got an early start. We picked our way through the pine forest that covered the base of the mountain. I led. With his left hand, Cody held my right arm above the elbow. In his right hand was his cane. He could sense from my movements where to go. My arm dipped, and he’d know to duck his head under a branch. I shifted left, and he’d know which way to step around loose rock.

Ninety minutes into our climb, about 8,500 feet up, we passed the tree line. I stopped in my tracks. For the next quarter-mile, the terrain was like a demolition site. Chunks of rock, some as big as refrigerators, were strewn everywhere. On either side was a steep drop-off. No way around. We’d have to scramble from boulder to boulder, hopping from one jagged edge to the next. Miss a step and… I didn’t want to think about it.

“Why are we stopping, Dad?”

I described the terrain and admitted, “I’m not sure we can make it.”

“Let’s try,” Cody said. “If we don’t make it this time, we’ll make it next time.”

He said it with such conviction, I felt ashamed at my doubts. I took a deep breath. “Okay, here we go.”

One slow step forward. Then another. Cody followed me from rock to rock, agile and surefooted as a mountain goat. Sometimes the only way to get from one boulder to the next was to jump a crevasse. I’d hop across, trying not to look at how deep it was. Then I’d guide Cody’s cane to where he needed to jump. My heart pounded each time, but he never missed a step.

It took us an hour to cross that boulder field. I was mentally drained. Cody? He was ecstatic. “Dad, that was great!”

The rest of the climb was steep, but not as difficult. Before we knew it, we were there—at the top. Cody couldn’t see the sweeping valley, the Grand Tetons in the distance. But he could sense the majesty of our surroundings. He stood as tall as he could and spread his arms wide. “Wow!” he exclaimed.

I knew the feeling. Only I wasn’t marveling at the view but at my son—how he’s never been afraid to try for a goal, how he always embraces all the possibilities he’s given. You don’t climb with your eyes, you climb with your hands and feet. And your heart. Cody showed me that. I can’t wait to see what heights he reaches next.

Download your FREE positive thinking ebook!