I lean back on the wooden bench and rest my eyes on the distant South Mountains. The day’s stresses are gone. This bench, with its thick wooden slats, seems perfectly placed, as if it has always been meant for this spot, a place of healing and comfort. It’s connected me to people—to a world—I would never have imagined.

Eight years earlier, in July, I’d just gotten back from an international business trip. I had this sore throat. It hurt to swallow, and there was a burning in my chest. It’ll go away, I thought. When it didn’t, I saw my doctor.

I had Stage III esophageal cancer. Shock wouldn’t even describe what I felt. The doctor was calm and reassuring, but I barely heard a word he said. My mind had already jumped ahead to the finish. At just 42, I was done. Game over. The world closed in over me. Life was reduced to me and that word: cancer.

I came home to my wife, Danielle, and our three children. “We’ll get through this,” Danielle said. “You can’t give up.”

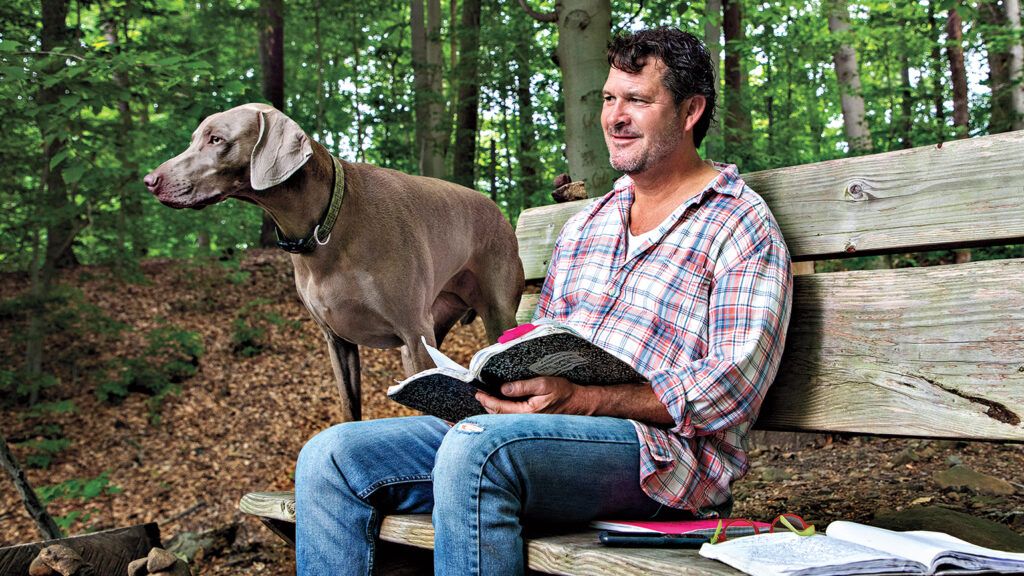

It was too late. I’d never felt more alone. I’d already given up. I paced back and forth behind my house, barely aware of everyone, everything around me: the trees, birds singing. My two Weimaraners, Mabel and Pearl, weren’t sure whether to follow or keep their distance. I’m a doer. Curious by nature. Woodworking and hiking the trail system behind my house were just two of my passions. But it felt as if I were already shutting down.

My oncologist prescribed a protocol of 11 chemo treatments spread over 14 weeks, with radiation five days a week for nearly half that time, and eventual surgery. “There’s a good chance of burns and blisters from the radiation,” he informed me. “And it might make swallowing more painful.” I dreaded everything about it. If it wasn’t for my family, I might not have even bothered.

The first radiation treatment, I lay uncomfortably on a table inside a body cast to ensure I didn’t move. Like a mummy. Already dead. The technician dimmed the lights. “Breathe in—one, two, three. Breathe out—one, two, three,” he intoned through the intercom. For years, I’d practiced meditation. Now I focused on the voice. Letting it lead me. Breathe. There was something unexpectedly soothing in it. For the first time, I relaxed. I let go.

My mother had given me a bottle of holy water from Lourdes, France, and I dabbed it on my fingers and made the sign of the cross after the treatment was over. I’d never thought of myself as tied to a particular faith. But in that moment, it seemed important, essential even, to seek protection.

Something awakened inside of me. I added homeopathic treatments and fresh-made juices to my regimen. In my meditation sessions, I felt at peace. I never experienced a single side effect from the radiation treatments.

There were six weeks between my final treatment and surgery. “Exercise as much as you can before then,” my oncologist told me. “Building up your strength will help with the recovery.”

I returned to hiking the woods behind my house, a 2,112-acre nature reserve. Pearl and Mabel went with me. I soaked up the beauty of the forest. The rustling of the leaves. Birds flitting about. My fear was fading. Still, there was a loneliness to facing down cancer that seemed almost inescapable.

The day of the surgery, Danielle went with me to the hospital. “Stay strong,” she said. “You’re almost there.” The surgery took nine hours. Then another 10 days of recovery. Danielle couldn’t be there every minute. I imagined what I would do when I got home. My family. Hiking. The dogs. One day a thought stormed into my mind: Build a bench. I loved woodworking. Danielle had a cedar chest I’d made for her when we were dating. I’d made a coffee table. Arty shelving for plants and knickknacks. A picket fence. With each creation, I wrote “a memory made” somewhere on them.

Lying in the hospital bed, I imagined what the design might look like. It made the time go faster. I envisioned the bench in the style of a church pew: solid, expansive. A place for unwinding. For reflection. And meditation.

I started on the bench a few months after I got home. I cut the pieces for the back and seat. Sanded the wood until it was smooth. I measured and cut the back supports. Then notched out a base. I was only strong enough to do a little bit each day, but there was healing in the work.

At last I was done. I inscribed “a memory made” on the back. Danielle loved it. So did the kids. I placed the bench in the yard under a favorite tree, but somehow it didn’t feel like the right location. This bench seemed destined for something more.

One day while hiking, Pearl found a trail I’d never gone down before. “Good girl,” I said. “We’ll call this Pearlie’s Path.” A few minutes later, we came to a small clearing, overlooking a bluff. The ravine was steep, the ground rocky. Far below, I saw the road that weaves through the reserve and, beyond that, a stream that feeds a pond. The canopy extended out like a green ocean to the mountains. It was breathtaking. I stood there for the longest time, not wanting to lose the moment. “We’ll call this Mabel’s Bluff,” I said.

As soon as I was strong enough, I dragged the bench there. I sat for nearly an hour, the dogs nosing about. My own private sanctuary. In the weeks that followed, I added birdhouses I’d made and handcrafted chairs. A wind chime. I’d close my eyes and let my mind go quiet. I thought of the day of the cancer diagnosis. How alone I’d felt. So much had changed. It was weird. I was all alone. And yet I felt a deeper connection to the world, to the universe, to God.

One Sunday morning, I took a walk to Mabel’s Bluff and was surprised to find a group of cyclists there, enjoying cold drinks, their bikes propped against the trees. “We love it here,” one of them said. “We stop by every week.”

I’d never thought of anyone else appreciating Mabel’s Bluff the way I did. But I liked the idea of it being a shared experience.

“It’s a pretty special place,” I said.

That chance meeting sparked another idea. I built a wooden box with a lid on it and left a composition book and a pen inside. “This is one of my favorite spots,” I wrote on the first page. “I’d love to hear what it means to you.” I figured it would be a kind of visitors’ book for the bluff, like you sometimes find in a bed and breakfast.

A week later, I read the first entry, written in beautiful script. “I’m weeping tears of joy and gratitude. I asked the universe to cheer my low spirits today, and look what it delivered.”

And below that another: “It is sad and comforting at the same time to know that the people who come here have struggles, problems and hurt, but this place can make those things disappear for just the briefest moment.”

Words I could have written myself. And yet they’d come from someone I’d never met. All of us part of a kind of community, facing different life challenges but united by an appreciation for the wonder of God’s creation. My hand lightly caressed the bench, feeling the strength of the wood. It no longer felt like my bench. Maybe it never had been. People regularly stop at Mabel’s Bluff, sit on the bench and pour out their feelings in the notebooks there. After four years, I have an entire collection of them. The writings inside aren’t only an outpouring of visitors’ emotions. Some of my favorite entries are those that have been written in response to other entries, offering comfort and understanding.

One person wrote: “Crying every day and wanting to give up, but for some reason I keep trying. Stupid, I know. At least I have this place to come to and get away from it all.”

The next entry said, “You sound like a great person…you got this.” Still another wrote, “You are not stupid; you are a soldier. Have faith in yourself. We all have greatness inside us.”

I waited to see if the original writer would reply. A few days later, I read: “Thank you so much. You have no idea how much this means to me.”

My life is fuller now than it has ever been. I make time every week to go to Mabel’s Bluff, a place where, even if I’m by myself, I am never truly alone.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.