Like a lot of people (and, I suspect, a whole lot of Angels readers) I talk to my dogs. “Why did you have to act that way?”

I’ll snap at my schipperke, Mercury, after he’s barked at a passing dog on the street for no apparent reason. “All he wanted to do was make friends. But no—you had to go and be nasty.”

Up and down my block each day other dog owners are doing the same thing, addressing their schnauzers, Pomeranians, Shih Tzus, and plain mutts in full, complex, impassioned sentences (while indoors still others are also doing the same thing with their cats).

Human beings may be, as the literary critic George Steiner put it, “the language animal,” but that doesn’t prevent a great many of us from talking to our fellow creatures as if they were language animals too.

Why does talking to animals feel so natural? Probably because, for most of human history, that’s just what it has been.

“It was, and still is in many places,” writes poet and anthropologist David M. Guss, “a widely held belief that the part of the animal we see is not the real part but only a disguise, an outfit it wears when it comes to visit our world.

“Once home again, it removes that costume and changes back into its true form—a form no different from that of humans.”

Natural as talking to our nonhuman companions feels, however, these conversations do tend to be a little one-sided. Most animals, after all, don’t talk back to us.

Most don’t…but not all. The idea that animals are at least potentially capable of communicating with humans goes back to earliest times.

Many biblical commentators over the centuries have suggested that before the Fall, Adam and Eve were able to discourse with the animals who shared paradise with them as naturally and easily as they could with each other.

Nor did the Fall entirely do away with people’s ability to understand animals—as Balaam’s ass proved when she verbally rebuked her master for failing to see the Angel of the Lord when he was standing right in front of them.

Even scientists—after centuries of arguing that human beings are the only creatures capable of language—are starting to sound a little less certain on the matter.

In 1977 a Harvard-educated animal researcher named Irene Pepperberg set about teaching an African gray parrot named Alex to talk. Not on the Polly-wants-a-cracker level, but really talk.

Alex soon developed a vocabulary of more than 100 words—including “ban-berry,” a word of his own coining, which he called apples because to him they tasted like bananas but looked like cherries.

In a recent National Geographic article, writer Virginia Morell described a visit she paid to Pepperberg and Alex (just before his death at the age of 30) at Brandeis University.

At a certain point in the visit, Pepperberg brought in younger parrots that were learning English with Alex’s help. Alex left off from talking to the humans and addressed his fellow birds—in English:

“Talk clearly!” he commanded when one of the younger birds mispronounced the word green.

“Don’t be a smart aleck,” Pepperberg said, shaking her head at him. “He gets bored, so he interrupts the others or gives the wrong answer just to be obstinate.”

Parrots are equipped with a vocal anatomy which, though very different from that of humans, allows them to mimic the human voice—something that other super-smart animals like dogs, chimps and dolphins have a harder time doing.

But it seems like some of these more vocally challenged species would like to imitate human speech, even if they don’t know how.

Donna Kassewitz, a researcher at SpeakDolphin.com, a Miami-based group working to break the human-dolphin communication barrier (and a faithful Angels on Earth reader), told me a story that bore this out.

Her husband, Jack, was swimming with a dolphin named Jupiter when Jupiter suddenly became quite animated. “He was really getting in Jack’s face—in a friendly but talkative and insistent way,” Donna said.

“While underwater, the dolphin began bobbing his head around excitedly while opening and closing his mouth and vocalizing. It was quite unusual for a dolphin to behave this way because dolphins don’t use their mouths to vocalize. Instead these sounds come through the blowhole on the top of the head.

“It seemed as if Jupiter was imitating the way humans talk in an effort to show that he wanted to communicate with Jack. Understandably, Jack couldn’t shake the feeling that there was important information that Jupiter was determined to share.

“Multiple times over a four-hour period, Jack thought the session with Jupiter was over and tried to exit the water, but each time Jupiter would gently grasp Jack’s arm, pulling him back in, and Jupiter would begin talking again!

“Eventually Jack was so exhausted from swimming that Jupiter kindly let him get out.”

Donna added, “The experience made us feel that the dolphins are probably just as frustrated as we are about our limited ability to understand each other. Events such as this galvanize our commitment to breaking the dolphin language code once and for all—in fact, we pray daily for God’s guidance in this research.

“It feels urgent that we give dolphins a scientifically undeniable voice in the world. We believe that when we do, humanity is going to discover that there are many important topics these creatures want to discuss with us.”

Such stories underline what most of us know already: Animals are kindred spirits. And though their consciousness may differ from ours in important ways, they are nonetheless beings with genuine inner lives, lives that they would, if they could, be happy to share with us.

Not that, by their very existence, animals don’t tell us plenty. “The word,” wrote the second-century Christian thinker Origen in his Commentary on St. John’s Gospel, “is present in every creature, however small.”

A century later Dionysius the Areopagite wrote that “since the creation of the world, the invisible mysteries of God are grasped by the intellect through creatures.”

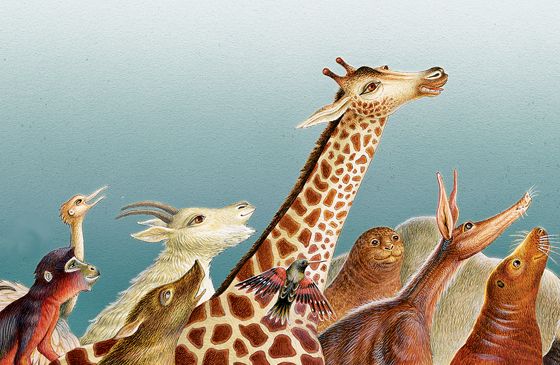

What both these writers are getting at is that just as all of creation itself is a kind of language (one that God spoke into being at the beginning of time), so too can all of God’s creatures be seen as actual words within that language. The sheer stunning variety of the animal kingdom bears this out.

The word “poet” originally comes from a Greek word meaning “maker,” and if creation is a kind of giant poem it makes sense that God would only be satisfied with the largest vocabulary of “words” possible.

Hence we live in a world inhabited not only by dogs, cats and horses, but by wombats, platypuses, pygmy gorillas, potbellied pigs, sea cows, capybaras, flying foxes, star-nosed moles, blue whales and every other manner of beast and bird and creeping thing as well.

But in all this glorious variety, one creature does stand apart: not through being intrinsically better than the rest of creation, but through the fact that it alone of all creatures was created in the exact image of God himself.

“The human being,” writes Christian philosopher Olivier Clement, “is a craftsman—and rational—qualities which we share with the higher animals, the difference between us being one of degree and not of kind.”

Though we humans, in other words, are in no intrinsic way better than the animal creation with which we share the planet, we are higher than they are on the ladder of being—the ladder which, according to traditional Christian cosmology, stretches from the lowliest earthly creature through humans and angels all the way up to God.

In fact, by virtue of our unique relationship with the creator we are higher than the angels, even though they lie above us as we lie above the animals.

It’s precisely this unique connection with God that gives us the awesome responsibility we humans carry here on earth.

As the sole and single truly God-like being in all of creation, it is our job, as the Book of Genesis proclaims, to exercise dominion over our fellow creatures: dominion not in the sense of tyranny and exploitation, but in the true meaning of the word, which is that of a lord who not only rules but protects the citizens of his kingdom.

How important is this task of stewardship that God has entrusted to us humans? Vitally so. As the animals in our company—from my dog Mercury all the way up to Jupiter the dolphin—would surely tell us if they could.

Download your FREE ebook, Angel Sightings: 7 Inspirational Stories About Heavenly Angels and Everyday Angels on Earth