I can still hear them. The rumbling that vibrated through the reserve that dry evening in March. Their grief-filled moans. The agitated movements of their ears. Those big eyes fixed on me and me alone.

My husband, Lawrence, always said there were things in this world that cannot be explained by reason, cannot be seen. Deep roots that connect all living things, humans and animals. It wasn’t until that night, two days after Lawrence died, that I truly understood.

This was a man who’d somehow charmed me into leaving my native France for an old Dutch farmhouse out on the savannah of Zululand in South Africa. A man who suddenly suggested we buy an old game reserve and transform it into Thula Thula, a lodge and an animal haven where leopards, zebras and white rhinos could roam free.

A man who, after watching a news report on the Iraq War, sneaked into Baghdad in the midst of battle to rescue trapped zoo animals. And then, of course, there were the elephants.

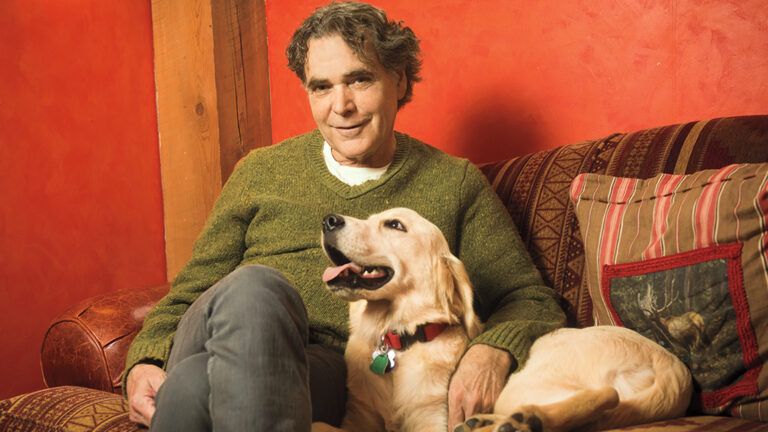

Everyone called Lawrence the Elephant Whisperer. He earned the nickname after adopting a herd of nine “delinquent” elephants about to be put to death. The herd was prone to escaping its protected habitat and rampaging through populated areas. Dangerous. Lawrence’s mind was made up, though. Maybe the elephants kept wandering because they weren’t in the right home, he said.

He had no knowledge of wild African elephants. Yet night after night, he camped out with them to earn their trust, a move that almost got him trampled. He sang to them, talked to them. Crazy, people said. But little by little, the herd took him in. First the matriarch, Nana, then the rest. They forged a deep bond, one based on trust and respect. The elephants stopped escaping and made Thula Thula their home.

Sometimes I tagged along with Lawrence on his visits to the elephants deep in the bush. Nana would extend her trunk to him and caress his face, as if he were a member of the family. The herd increased to 21 elephants and our property doubled over the years. But the bond remained. So did Lawrence’s nickname, though he preferred to be called the Elephant Listener.

“I don’t have a special talent,” he told me. “The elephants talk to me if they want to. If they don’t want to, I don’t insist. I just listen.”

I only wished he’d listen to me every now and then. Lawrence was physically strong, a robust six foot three. But lately he’d been having heart trouble. In September, at the age of 61, he’d suffered his second heart attack. He wasn’t supposed to fly, but he had insisted on traveling to Johannesburg for a weeklong business trip to help advance the mission of Thula Thula.

“Françoise, I’ll be fine,” he said before he left. “There’s no need to fret.”

The call came at seven o’clock in the morning on Friday, March 2, 2012. I was awake early, straightening up the house in preparation for Lawrence’s return. On the phone was David, Lawrence’s right-hand man, sobbing. I caught only snippets. Lawrence. Unconscious. Heart attack.

“I’m…so…sorry…Françoise,” he said. “He’s gone.”

I clutched the phone. “Impossible, impossible,” I whispered. But deep down I knew it was true.

The news hit Thula Thula like a bomb. Our staff of 70 was inconsolable. Lawrence wasn’t just the boss. His Zulu name was Mkhulu, or “grandfather.” That’s how everyone saw him. I knew they needed me to be strong, to assure them that we’d be okay, even without Lawrence. But I couldn’t think, couldn’t speak. My head was lost in memories.

Like the first time we’d met. Waiting for a taxi in London, where we had both gone on business. It was freezing, a mix of rain and snow. I finally made it to the front of the line. The concierge asked if I’d mind sharing a ride with the man at the back, also headed to the convention center.

Lawrence was wearing a bright blue windbreaker in the middle of January, as if he were on safari. No way was I sharing a ride with that guy. “No, no,” I said.

To my great surprise, I ran into him later at a Tube station. It was hard to miss that windbreaker. This time, I introduced myself, apologized for my rudeness. It was one of those moments orchestrated by that invisible force Lawrence believed in. We met for dinner and a jazz show. One year later, I left Paris, headed for South Africa. It was easy to face the unknown with Lawrence. He made me less fearful.

I didn’t want to face the unknown without him. Didn’t want to live in a world without his fierce spirit and generosity. Life without Lawrence? Impossible, impossible!

Two days after Lawrence’s death, a Sunday, I was still holed up in our bedroom. People passed in and out of the house, paying their respects. It made no difference to me.

“They’re here!” someone said with a gasp. Who was here? The voice was followed by shouts. All kinds of commotion. What was going on?

I dragged myself downstairs and opened the front door. The staff was gathered outside, all staring in the same direction, eyes wide. On the other side of the fence on our property were 21 distinct gray shapes. The elephants. Lawrence’s elephants.

Nana gazed at me. So did the rest. As if they were waiting for something. Or someone. They remained like that for more than an hour, then marched up and down along the fence, rumbling. The same noise they’d always used to “talk” with Lawrence. They seemed edgy. Distressed. Finally, they lined up one by one and made their solemn procession back into the bush.

The work at Thula Thula continues, as my husband would have wanted it to. Most people have moved on. But an elephant never forgets.

The year after Lawrence’s death, on March 4, the elephants returned. Led by Nana in the same procession. The year after that, again on March 4, they were back. And again on March 4 the following year. They mourned him like one of their herd.

How did they know? Who sent them? What does it mean? Some things in this world are beyond human understanding—cannot be explained by reason, cannot be seen.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.