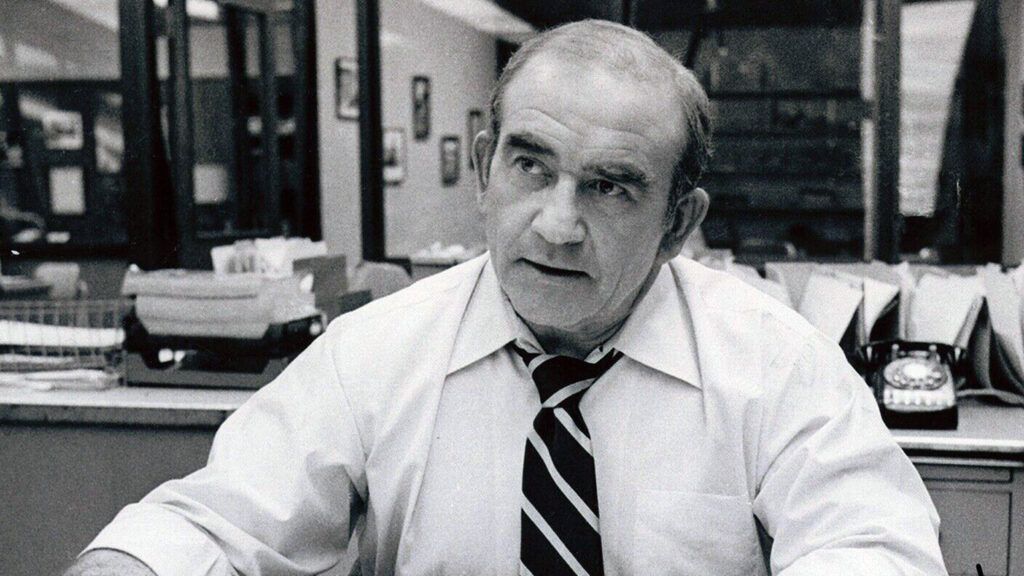

My heart was pounding as I stood in the shadowy wings of the University of Chicago’s theater. It was summer term, August, 1951, and the intermission for our student production of T.S. Eliot’s Murder in the Cathedral was nearly over.

I could hear the sound of the audience returning to their seats. Nervously, I tugged at my belted costume. The musty purple garment was unlined and scratchy.

I was playing the lead role—Thomas Becket, Archbishop of Canterbury in the year 1170. Becket was a Christian martyr, a man who lived and died in 12th-century England, in loyalty to his faith.

So far, the play had gone well—but I was more than a little nervous about the upcoming final act.

Back in high school in Kansas City, Kansas, I had performed in many radio dramas, but this was my first try at stage acting. Since I’d been in college, I had dabbled in a lot of subjects, but acting was the only thing that held my interest.

For this reason, more than any other time in my life, I wanted to do a good job.

Restlessly, I tapped my foot.

Don’t worry, I told myself. You know your lines. You’ll do fine.

But the anxiety I was feeling ran deeper than the usual case of opening night jitters. From the first rehearsal, I had felt unsure about the Becket role.

There was a part of his character—the essence of the man—that I couldn’t grasp. His relationship with God seemed so intense, so personal. I couldn’t understand it.

Hey, I told myself again. Take it easy. But I couldn’t stop worrying. Amid the confusion of backstage activity, I mentally reviewed the script, considering the events leading to the big final scene—Becket’s martyrdom in Canterbury Cathedral.

Under my breath, I murmured his final words of faith, hoping that this time I might somehow experience first-hand what Becket felt. It was my last chance.

“For my Lord”—I paused dramatically, waiting for inspiration—“I am now ready to die.”

But nothing happened. As usual, the words came out flat and empty. In the silence that followed, I flinched with the bitter realization that I would probably never be able to put myself in Becket’s shoes, no matter how hard I tried.

But, I asked myself, how could I be expected to? I was a 20th-century American Jew. What could I possibly have in common with a 12th-century Christian martyr?

The more I brooded about it, the more discouraged I became. This wasn’t the first time my faith had seemed a stumbling block to my hopes, dreams, desires.

Memories of growing up in Kansas City as one of less than 100 Orthodox Jewish families in a city of 120,000 came flooding back…

It was four p.m., on a gray and muggy afternoon. I was a chubby little kid, waiting after school for the city bus (which was late) that would take me to the streetcar, that would take me to another city bus, that would finally drop me off at Hebrew school.

All the other kids were having fun playing football or basketball, and visiting each other’s houses and eating peanut butter and jelly sandwiches.

The sound of laughter caused me to look up as a group of classmates approached, grinning and joking and taking playful punches at one another. When they saw me, they waved hello, and stopped for a minute to talk. Then they moved on.

I liked them a lot—and I think they liked me, too. But they knew I was different.

As I watched them walk away, I tried to ignore the hollow pit in my stomach. My fingers reached deep into my jacket pocket and curled around the soft, flat yarmulke that had been tucked there since morning.

I would put it on this afternoon before entering the synagogue for lessons with the rabbi.

Sometimes I wondered what it would be like not to be Jewish; to be able to play with the other kids after school; not to have to wear a skull cap; to worship on Sunday instead of Saturday.

But then I chased away such thoughts with warm recollections of home and family behind the red brick walls of our two-story house on Oakland Avenue…the sweet aroma of fresh-baked challah wafting from Mama’s always bustling kitchen; the candlelight magic of sundown seders; the mystery and wonder of shared prayers and songs around the dinner table on High Holy Days.

Still, I had to face the fact that when I was away from home, I was lonely. Sometimes a deep fear gripped me—a cold, hopeless feeling that I would never have friends, never be accepted, never be “normal.”

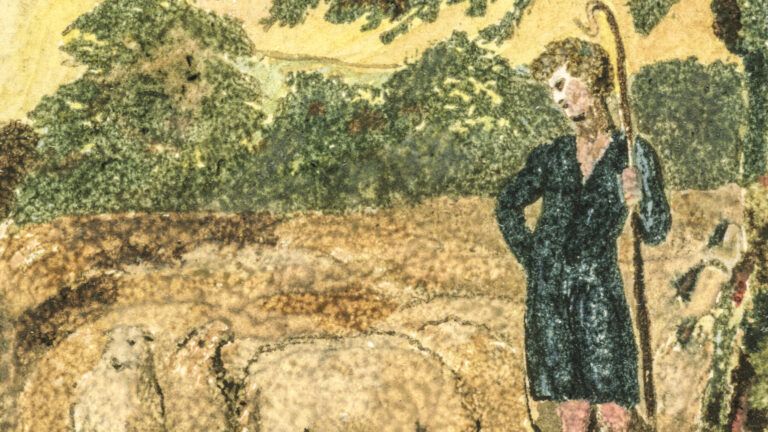

At moments like this, my best friend was my imagination. While waiting for the bus to Hebrew school, I entertained myself by lapsing into fantasy about my favorite Biblical characters.

Like a mighty army of superheroes on parade, they thundered past the reviewing stand of my mind. First came Abraham, wise and faithful patriarch. Then came his son, Isaac, with grandson, Jacob—who later became known as Israel—and great-grandson, Joseph.

Fearless Samson followed, his spectacular mane blowing in the wind. Daniel was there, too, flanked on either side by a pride of protective lions, like so many loyal dogs. All passed by in glorious procession.

Then, finally, came Moses. His face shone brilliant with the light of the Lord. His eyes were ablaze with his vision of the Promised Land—the land he would safely lead his people to, but would never reach himself.

Truly, I wondered, these were all great men of God; men who lived and died in loyalty to their faith…

“Ed!”

I jumped, startled. It was the stage manager.

“Five minutes to curtain,” he said.

“Thanks,” I acknowledged.

At the thought of going onstage, my old anxiety returned with staggering force. I felt like a little kid again—afraid of failing, afraid of being rejected.

Suddenly—and quite unexpectedly—I heard myself saying, “Lord, help me do a good job. Take away my fear. Let me live this role; let me be this man, Becket, who died so bravely so long ago. Don’t…” I hesitated. “Don’t let our differences stand in the way.”

As I took a deep breath and walked on stage for Becket’s final scene, my heart was racing.

Why, I thought frantically, should this time be any different from the rehearsals?

But this time, something was different.

God must have heard me, because suddenly I understood that the God Becket prayed to and died for was none other than the same God of my childhood—the same God Who spoke to Abraham, the same God Moses saw face-to-face.

The differences between Christianity and Judaism were great, certainly. Yet there was this tremendous heritage that we shared; faith in one Father, Creator of us all. Where once it seemed that Becket and I were strangers, now I knew what we had in common.

Finally, I understood the man.

“For my Lord,” I heard my voice ring out with newfound conviction, “I am now ready to die!”

The words shot out like blazing arrows into the darkened theater. They must have hit their mark; the performance earned good reviews. From that night on, I knew I was destined to be an actor.

Most importantly, I knew that never again would my faith be a stumbling block to my hopes, dreams, desires. Rather it would serve as a mighty bridge to meet them.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.