When I was 15 years old, I read an article about a boy my age, Billy Clayton, who had just become an all-American skeet champion. “I wonder if I could beat that kid,” I said to myself.

For a year I spent every afterschool hour shooting and then entered my name in the competition. Billy and I tied for first place. There was a shoot-off and, incredibly, I won.

Well, this just reinforced something I had always suspected: the guy who works hardest wins. The idea excited me, and I went looking for competition. My brother Jim and I entered the international outboard championship. Together we took six different racing trophies.

ENJOYING THIS STORY? SUBSCRIBE TO GUIDEPOSTS MAGAZINE!

When we moved to Los Angeles, I threw myself into polo the same way. Polo was especially interesting to me because it drew me together with men who were my heroes off the field as well as on it: Spencer Tracy and Cary Grant.

I think they liked the youthful drive I put into the game; too bad they didn’t warn me that life requires more than that.

Or perhaps in his own brusque way Spencer Tracy did try to pass on the message. I was still in my teens when I decided that I wanted to become an actor. One day I told my idols. Spencer slouched down in his saddle and turned to Cary.

“Too bad!” he said. “We’ve just lost a good polo player and gained a lousy actor.”

I think he was talking about my overly competitive spirit. It might be an asset on the polo field, but Spencer knew that outside the limited world of sports, effort and results do not always go hand in hand.

I saw this myself as my training as an actor began. Every time a part was cast there would be general grumbling. “How come she got that part? My tryouts were better.” And the trouble was, it was often true.

There is an ingredient in success which goes beyond effort, even beyond talent–an element of luck, of knowing the right person, of being in the right place at the right time, of simple, gratuitous fate.

How the competitor in me resisted this idea! I rejected it even when luck stepped in and smiled on me personally. I had a tenuous claim to friendship with Deanna Durbin: I was the “friend of a friend.” So trading on this close relationship, I visited this young actress one day at her studio.

While we were talking, the director walked in. He took one look at me and asked, “How’d you like to play opposite Miss Durbin?”

READ MORE: MICHAEL LANDON ON GOD’S BLESSINGS

I thought he was joking. He hadn’t asked if I could act, or even if I wanted to. I “looked the part,” and for no stronger reason than that I was offered a chance at a dream.

When the announcement was made that I was playing the male lead in Deanna Durbin’s new picture, I’m sure a lot of young actors asked each other, “How come he was chosen? I’m better trained.”

Yet in spite of Spencer Tracy’s veiled warning, and in spite of my own luck, I still could not abandon the idea that success just had to depend on outdoing the other guy. I hadn’t realized how deep that attitude ran until the night I met a discerning young man. As we shook hands he said just seven words:

“You don’t like to lose, do you?”

If competitiveness was starting to show in my face, I thought, it was time I took a careful look at myself. A person who helped me do this was a young girl, Rosemarie Bowe, who had just come to Hollywood from Tacoma, Washington.

One day I was in a roomful of actors when Rosemarie walked in. Here was a very pretty young actress, new to Hollywood–potentially a threat to some of the older women in the room. I’d seen the situation many times and knew how vicious the infighting between the ladies could be.

Sure enough, two of the older gals started in on her: the snide remark, the innuendo, the small cruelties. I watched to see how Rosemarie would counterattack.

She didn’t. It was as if she literally did not hear. As naturally and unselfconsciously as a child, she stepped up to those two women and made friends of them. Before long they were following her around—as though they fed on her security.

READ MORE: KARL MALDEN ON FINDING PEACE

Sometime later, when I met Rosemarie again, I told her how greatly I admired the way she had handled the two women and asked her how she did it.

“I’m not in charge of my own life,” Rosemarie said. “Once I discovered that, I stopped thinking of other people as threats.”

It took me some time to discover that when Rosemarie said she wasn’t in charge of her own life, she meant that God was. It was basic to her whole outlook, and it was basic to my feeling that this was a girl I wanted to live with for the rest of my life. Rosemarie and I were married in January 1956.

And right away she began trying to teach me to look at my career with detachment. “There’s nothing wrong with working hard for what you want, Bob,” she’d say. “But over competitiveness can cripple you. It can take all the fun out of life.

“Besides, you probably have less to do with your success and your failures than you like to admit. Think back over the roles you fought hardest for and didn’t get. How many of them were successes?”

It was true. Time after time the roles I had tried for and lost were wrong anyway. In one, for instance, the film was never released. In another the movie was shown a few times and then shelved. On the other hand, roles which came to me most casually had turned out to be my best opportunities.

“That is no accident,” Rosemarie said. “You really ought to join me more often in my morning time.” This is the time she saves each day for meditation. “Perhaps you could learn to see that what seems like luck is often God’s way of directing your life.”

READ MORE: ROBERT YOUNG ON GOING TO CHURCH

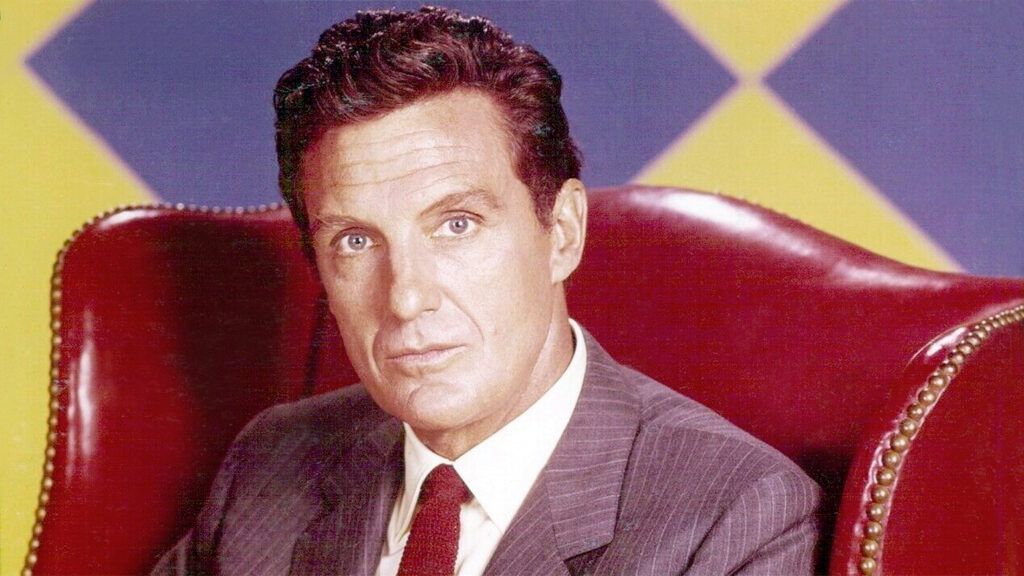

I did join her—hesitantly at first, then with greater conviction. One day I got a telephone call from my agent. He wanted me to consider the part of a Federal agent named Elliot Ness, in a new TV show to be called “The Untouchables.”

My first reaction was altogether negative. Television? I was more interested in the movies than in TV.

Furthermore, I learned that I wasn’t first choice for the job. Van Johnson had turned down the role. I finally decided to do it. But the old overly competitive spirit was dealt still another blow when the tailor, arriving with the specially made 1920s suit, greeted me with, “Your clothes are ready, Mr. Johnson.”

Rosemarie laughed when I mentioned the tailor. “Maybe your ego is being crushed on purpose,” she said. “Maybe God has something special for you to do in this part.”

I wondered. It had, in fact, long bothered me that violence and evil were so often given glamor treatment on TV. Perhaps in this new role I could counter that trend. When I talked with the producer about the part, I told him I wanted to show violence every time for what it —ugly.

And the remarkable thing is that this show, which nobody wanted to do, became one of the longest running and most honored vehicles on the air. I am convinced this success came because it had a message that was relevant to our times.

So the competitive spirit in me is finally taking its rightful place. Controlling my beat-the-other-guy instincts has been a matter of discovering God.

Today I know that every time I yield myself to His plan, He uses me in ways that have never even occurred to me. My responsibility is to do my best wherever He puts me, and to leave the outcome to Him.

Perhaps that’s the toughest role I’ve ever had to learn.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.