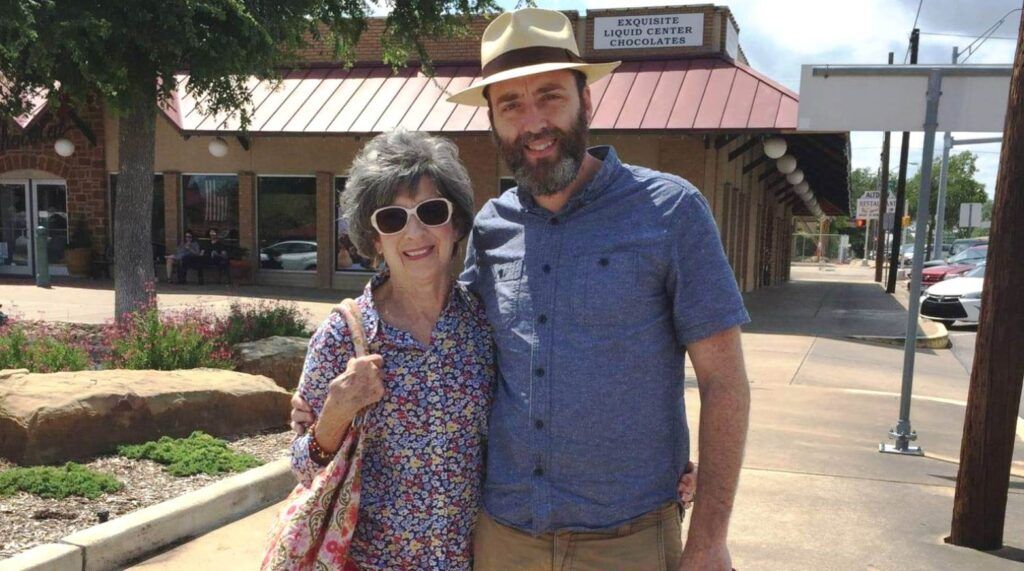

Earlier this year in northern Alabama, as my mom hit the final stretch of her decade-long battle with breast cancer, she sat in her hospital bed and turned herself into my agent. Doctors, nurses, friends and family came into the room to check on her, and she pushed my new prayer book on all of them. She told them to buy copies for their church groups and that I would be happy to come speak. I could do a conference call or make an appearance via Skype, she said—just let me know what they wanted, and I’d do it, so long as they bought the book. We all got a kick out of her salesmanship, and we were delighted she had so much coherent energy. Just days before, she was so sick with the ravages of chemo that she could barely speak. When she found her strength, she used it to tell everyone about her son’s new book.

That book, The Prayer Wheel, co-authored with Jana Riess and David van Biema, is dedicated to my mom (along with Jana’s dedication to the late Phyllis Tickle and David’s dedication to his wife and son). Dedicating it to her was in some ways my original motivation—the project was David’s idea, not mine, but one reason I said yes to it was that I wanted to have a public acknowledgement of my mom’s legacy. She’s a giant to all who knew her, because she lived a full, hard, epic life, and she survived and even flourished in that life by devoting herself to daily prayer.

Mom was raised by a single mother of four in northern Mississippi. Her mom used to pretend they were camping at home on Sunday nights—that’s how she made it fun to eat only cornbread and milk, which was all they had. Mom married at 19, to my father, who made her life much harder. Alcohol, drugs, state-to-state moves that never made much sense. She spent her 20s, 30s, and 40s raising my sister and me well in spite of my dad, teaching us to love, forgive, persevere.

If you met her at a party, or more likely at church, you’d never know this hard life—not because she hid her pain, but because she wore it lightly. She worked off the weight of her burden every morning in prayer, often again in the afternoon and night. She worked it off so well that she had plenty of room for other people’s burdens, their joys, their needs and hopes.

Mom had a big community of friends—a sizable portion of Alabama and Mississippi made their way to her hospital room in the last couple of weeks, paying their respects to a woman who loved them without condition, and helped them love their own lives a little more.

I’m hardly the person of prayer my mom was; I’m hardly the person of faith she was. What faith I have, and what prayers I pray, are largely the result of her example, which has been hard not to mirror even when faith has been hard to come by.

Every morning, Mom would be at the kitchen table sitting over her Bible, her lips moving, her face focused. Her Bible looks like this:

Hundreds of pages look this way. It’s a workbook, a journal, a record of her interior life. It’s a timekeeper: note the margins with all those dates, which go back to the early 1980s. Sometimes the dates are labeled with words and phrases, like “depression” or “cancer,” or people’s names — my name is in there a lot, which tells me that on many mornings of the last few decades, my mom was pleading, blessing, thanking on my behalf. Prayer was her life’s work. She worked several jobs in her day, and oversaw a challenging home. But her main career was prayer. I recently heard a recording of my mom praying at my niece’s wedding shower, and it was proof of her skill, her profound accomplishment. She was a master of prayer.

Whatever you believe about the efficacy of prayer, however you think it counts in the workings of the world, we have in people like my mom lifelong testimonies to the power of prayer. She survived a tough life with her heart not only intact, but full of joy. She was filled with thoughts of other people and how she might serve them. She had and felt deep wounds, and sure, she made mistakes. But she struggled against the darkness, lest it settled in. Her response to hard things was to hear them, see them, not deny them, then hope against them. Those are hard-won emotional and spiritual resources, and the way she won them is prayer.

At the end, I watched Mom walk a tightrope. She believed God could heal her body. She also knew her body was failing her. Somehow she held those things in tension. When we first met with the palliative care doctor, he told her—with compassion and grace in his eyes—that she probably had three weeks left to live, tops. She smiled at him, and said, “Okay. I understand. That’s your report. But God has a report, too.

Mom spent her life straining to hear God’s report. Some people might call that kind of faith a reality-denying impulse, a stubborn wishful thinking. Mom showed it to be something else: a steady path through the dark wood of life, a reminder to look up and see the light shimmering through the trees.

PATTON DODD is coauthor of The Prayer Wheel. He has held senior editorial positions at Beliefnet, Patheos, and OnFaith. His writing has appeared in Christianity Today, The Wall Street Journal, Washington Post, TheAtlantic.com and Slate.