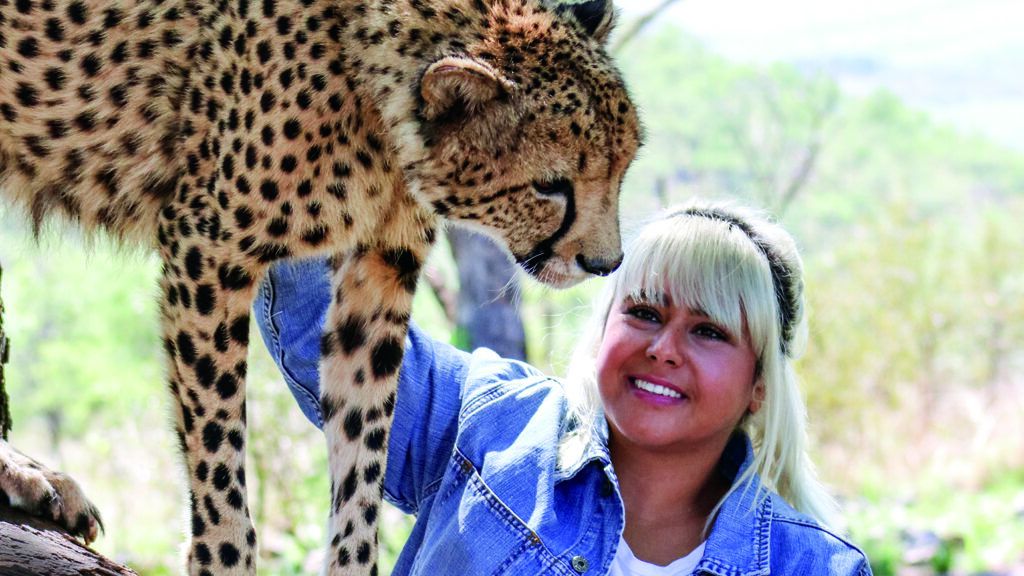

Sonia Perry may have grown up in New York City—in Astoria, Queens, to be exact—but she’s always been drawn to protecting wildlife. It wasn’t until the loss of her father, who first introduced her to animals, that she decided to drop everything and pursue her dream. Now the 32-year-old conservationist is opening her own sanctuary where zebras, elephants, lions and other animals can live safely in a natural habitat.

How did a city girl become an animal lover?

My father would take me to the Queens County Farm Museum to see the sheep, lambs, horses, cows, chickens. I loved it. I watched Steve Irwin and other wildlife shows. I also worked upstate for a friend who had many exotic animals. And I did part-time work with other farmers and master falconers. I wanted to gain experience. Yet, despite loving animals, I went into the corporate world, spending years as a senior project manager.

What made you rethink your career path?

Corporate life wasn’t fulfilling for me. I felt a void. My father’s death in 2017 really woke me up. I wanted to do work that gave me purpose and fulfilled my longtime dream of working hands-on with animals. I had promised my dad that I’d travel to Africa. So I dropped everything and embarked on a journey.

How did that 180-degree turn happen?

I researched online and found a program at a reserve in Zimbabwe. I didn’t even know where that was on a map! But they accepted me for a three-week program, which turned into a year.

What animals did you work with?

Lions, some as young as three months old; zebras; orphaned elephants; black and white rhinos; wild dogs; spotted and striped hyenas; cheetahs; servals; and leopards.

We were researching and tracking. We’d go out in a truck and make sure they were safe, healthy and uninjured. There were days when we discovered an animal caught in a snare, immobilized and bleeding, and we tranquilized them in order to heal them. Snares can cause serious pain and sometimes even death.

We were caregivers who had to be armed because of poachers. We built bomas—secure enclosures for the animals to sleep—and made sure they were doing well with their cubs. We walked with the white rhinos, taking them to different enclosures and enrichment areas to stimulate their minds with new smells and features. The lions needed enrichment programs too, so we made toys for them from elephant dung and built them play areas. But protection was always the priority. We couldn’t fence hundreds of hectares [one hectare is more than two acres], so we had to protect the area for their safety and ours.

Is poaching a big problem?

Yes, and in many countries. Close friends of mine lost their families in the Congo due to poaching. There, 20 caregivers were killed, along with gorillas and rhinos. A sliver of a rhino horn goes for $10,000. These animals are so smart, and it’s so sad some people are willing to kill them.

Was it difficult to live in the bush, so far from home?

It was rare to meet another American, but I loved interacting with people from all over the world. I cooked and ate with the local people and they became family. It was a lot of learning, improvising, surviving and adapting. Every day was different. There were constant protests. When Robert Mugabe resigned as president of Zimbabwe, people couldn’t buy food or get money. There were some days without electricity. It was an adventure, never routine.

And then you were able to explore another area of Africa?

I traveled extensively through East Africa, camping in Serengeti National Park and Ngorongoro Conservation Area in Tanzania. It was one of the most difficult yet enlightening experiences of my life. I was in extreme conditions with bare necessities, cooking my own meals, hoping I didn’t get attacked by wild animals. But watching a herd of elephants walk nearby was breathtaking.

After a little more than a year in Zimbabwe, I went to a sister reserve in South Africa for about eight months. My favorite animals there were the African wild dogs. I let them slowly get used to me, and by the end of the trip, three of them would sit next to me. Animals want to gain trust, want to know you’re there for their benefit and that they can rely on you. I’ve bonded with so many. I wouldn’t see an animal for months, but when I returned, they came running to me. It was a majestic experience.

What were some of your favorite experiences?

I loved interacting with lions and elephants one-on-one, bathing and feeding them, and creating enrichment programs for them. It felt so amazing when they trusted me, when I walked into a lion enclosure, and a one-year-old cub ran up and hugged me.

What do people need to know about animal preserves and sanctuaries?

There’s a misconception that animals are there in captivity. But this is a natural habitat they’re in because of unscrupulous hunting—up to 20 percent of certain species are being killed, so we need to protect them. They live longer in a preserve. Animals are important to our ecosystem whether you live in Zimbabwe or Queens.

How did you decide to start your own sanctuary?

Seeing these animals living under human care and being able to interact with them, I realized this is what I was meant to do. I was inspired by a younger woman I met during my travels who has her own sanctuary. Meeting “The Lion Whisperer” Kevin Richardson was also incredibly moving. I could see his unmeasurable love for these animals by the way he’d do any and all tasks needed for their care.

It can’t be easy…

The economy in South Africa is so different. You can buy land, but you need to be careful that it hasn’t already been claimed by a local. And you need to make sure you get a permit processed through the government, proving you won’t be breeding or allowing trophy hunting. You need to benefit the country and the animals. Otherwise, they can take it away from you. I’ve had so much help.

When will your sanctuary open?

After extensive work, it will be finalized this year. I can’t wait! I was able to save enough to buy my own private game reserve in South Africa. I’m calling it Hapana Miganhu, which means “no boundaries” in Shona. To wake up and see an ostrich running around, zebras and baby baboons, knowing I get to rehabilitate injured or orphaned animals and perform rescue and release—these things make me feel alive. You have to be empathetic and compassionate to do this work, and that’s who I am. I would do anything for these creatures.

For more inspiring animal stories, subscribe to All Creatures magazine.