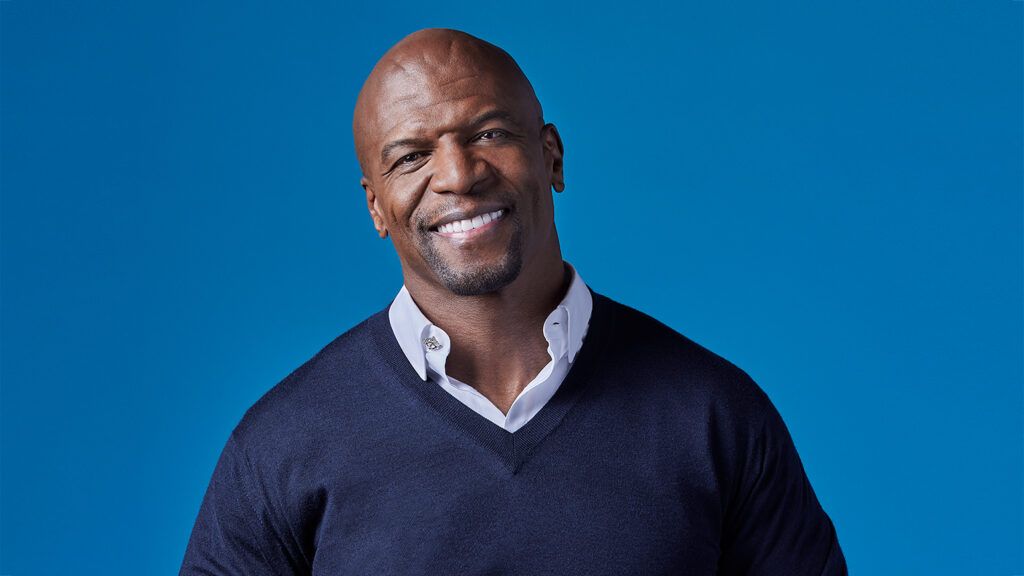

If you’ve seen me on television—on America’s Got Talent, Brooklyn Nine-Nine or Everybody Hates Chris, for example—or in movies such as The Expendables, you know I’m known for my big muscles and alpha swagger. Yeah, I bought into that hype too. Sure, the image allowed me to support my wife, Rebecca, and our five kids in style. But it went deeper—and darker.

What I couldn’t let anyone—even myself—see was that inside I felt inadequate and vulnerable, like the seven-year-old boy I used to be. A boy who was desperate for his parents to stop fighting, desperate for his father’s love.

I grew up in Flint, Michigan, the middle child of three. One of my earliest memories was of seeing my father, drunk, knock my mother to the floor. This happened regularly. Even so, I was considered lucky by neighborhood standards because my father was around and didn’t beat us kids. He was a foreman at the GM plant, a hard worker and a good provider.

My mother would say things to lay him low. She liked to scream about what a sinner he was. She was a devoted churchgoer, and she took us kids for hours-long services and Bible school. But her church was as dysfunctional as her marriage.

The pastor didn’t preach about God’s love and grace. Instead, he preyed on his congregants’ shame about their weaknesses and their fear of hellfire. What I learned was that you didn’t ever cross God. His wrath and judgment came quickly. I wanted to hide from God. He was even scarier than my earthly father.

Still, I loved my dad and yearned for him to love me. What boy doesn’t? I would watch him get ready for work. I’d try to make conversation about how he shined his shoes (he had served in the Army and still dressed with military crispness) or whatever else I could think of, but he’d give clipped answers, as if to say, “Leave me alone.”

After finishing his shift at the plant, he’d go to the American Legion hall and drink, come home, fight with my mom, yell at us kids or just sit in his chair in a stupor.

One Friday night when I was in second grade, my dad stomped into the living room, put on some sad soul music and slumped in his chair. He looked so pitiful sitting there all alone, listening to Bobby Womack. My heart ached for him. I tiptoed over, put my arms on his broad shoulders, leaned in and gave him a kiss on the cheek.

He turned and stared at me in shock, as if my love was the last thing he wanted. I backed away so fast, I almost tripped. I decided then and there that I could never let myself be vulnerable again, as if I had discovered the key to my survival. Not that I knew the word vulnerable but the message was unmistakable to me: “Squash your feelings. Get tough or get eaten alive.”

Getting tough meant getting bigger. I loved art. I would sit at the kitchen table and draw superheroes with bulging muscles. I dreamed of becoming strong and powerful like that.

There was a community rec center down the street from Flint Academy, the magnet school I got into in seventh grade because of my artistic talent. At 13, I discovered the gym in the rec center’s basement. I lifted weights every day. I liked being able to control something in my life, even if it was just the way my body looked.

I could make myself look fearsome. Muscles were my superpower. Somehow, I knew my father would go too far one day, and I would need to be strong enough to take him out. No boy should have to grow up thinking like that, but at the time, I didn’t know any different. It was my reality.

I threw myself into sports. My muscles served me well, especially on the football field. Being an athlete also got me a pass from the gangs in the neighborhood. I entered Western Michigan University on a partial-tuition art scholarship. I made the football team as a walk-on.

It was there, in Kalamazoo, Michigan, that I met Rebecca King. A friend from my dorm invited me to go to church with him and his girlfriend. I was leery, given my experiences at my mom’s church. But this place had a totally different vibe, starting with the music.

Then I saw the piano player. I felt drawn to her in a way I couldn’t explain. After the service, my friend introduced us. Rebecca was a single mom with a baby. She had her own apartment, worked in a hair salon and played piano on the side. She was way more mature than I was. Still, she gave me a chance.

I had no idea what a healthy relationship was, but I knew I needed to be with Rebecca. On one of our first dates, I told her, “I don’t know where this is going to go, but I want you to know I’m willing.” It wasn’t something I planned—I never would’ve planned to open up like that. It just came out. We got married a year later, in July 1989, and started a family.

I spent seven years as a journeyman player in the NFL, a lonely existence that reinforced I could never show fear or weakness. Vulnerability and pro football don’t exactly mix. My career dictated where our family lived. I thought as husband and father I should dictate what we did. The one thing Rebecca insisted on was raising our kids in the church. In every city, she’d find a church for our family to go to. And I’d go. For her and the kids.

A year after I left pro football, we were living in an extended-stay hotel in Los Angeles, broke, mainly because I was a big spender and wouldn’t listen to Rebecca, who was frugal. (“The borrower is servant to the lender,” she’d say, quoting Proverbs.)

I got a job as a security guard on movie sets. People in the business told me I belonged in front of a camera. With Rebecca’s encouragement, I auditioned for a new reality show, Battle Dome, and landed my first TV role.

We finally had enough money to fly back to Flint for Christmas. One night, Rebecca and I let my parents babysit while we went out to dinner. My dad promised not to drink around the kids, and I decided to trust him. Big mistake. My parents got into one of their epic fights, my dad punching my mom and knocking one of her teeth sideways. My sister-in-law called and said my mom and our kids had fled to my aunt’s house.

That terrible moment I fantasized about as a kid had finally come. I broke every speed limit between the restaurant and my aunt’s. I dropped Rebecca off and rushed to my childhood home. I burst in and found my dad in the kitchen. “What the hell do you want?” he snarled.

“I’m grown now,” I told him. “And you will never lay hands on my mother again.”

Then I punched my father in the face. Hard. Years of anger were bound up in that fist.

All the impotent rage I’d felt as a child came pouring out. I hit him again and again. Finally I was spent. I stared at my father, lying on the floor, whimpering.

I’d dreamed of this moment, how good it would feel once I showed how strong and powerful I was. How I was in control now. But all I felt was empty. Hollow. My dad wasn’t the only one crying. I bawled like a baby, full of shame and remorse. I’d never felt so vulnerable than at that moment, worse than when my dad had shunned me all those years before.

We went back to L.A., and I went right back to being the alpha male with my wife and kids. I never raised my hand to them, but I tried to control them just the same. Like buying my kids the toys they wanted, then using that as leverage to lay down the law. If that didn’t work, I’d lash out verbally.

Or like the time I traded in Rebecca’s car and got her a brand-new Escalade after I got a lead role on Everybody Hates Chris. It had rims, tinted windows and everything. She didn’t want a new car, let alone something that flashy. I wanted my wife to have this status symbol because it would make me look like a big shot. I told myself I was being generous, but really, I was trying to earn Rebecca’s love with gifts. Deep down, I didn’t believe I was worthy of her love or anyone else’s—especially not God’s. I’d sit in church hoping he didn’t notice me.

The more success I had, the more bad-tempered and controlling I got, fearing it would evaporate any minute. Rebecca begged me to tell her what was going on, but I kept it all inside, all my fear and confusion, until the feelings were like a dam about to burst.

One day in February 2010, I was on location in New York City. Rebecca was home in L.A. We were arguing on the phone, and I finally broke down and told her everything I’d tried to keep hidden, emotions I didn’t even understand why I was having. Primal fears of vulnerability and loss of control that my muscles could no longer conceal.

“I love you, Terry, but if you don’t get help, I don’t see us working this out,” she said, then hung up.

I needed guidance. I picked up the phone and did something the younger me would never have considered. I called my pastor. We’d been going to Faith Community, led by Jim and Marguerite Reeve, for a while. I still thought of church as something I did only for my wife and kids. Yet somehow I knew I could trust Dr. Jim Reeve with the darkest parts of myself, as if I were being led to him.

I told him everything I’d told Rebecca, my darkest secrets, the muck of my soul. Jim listened. Then he said, “Terry, I can’t promise you you’re going to get your wife and your family back, but I can tell you that you need to get better for you.”

I had thought you did good things to avoid punishment and earn approval. Now here was a man I respected telling me to be a better person simply for the sake of being a better person. It wasn’t about what others thought of me. It was about what I thought of me. Like a burst of light, that simple wisdom changed my life.

That and a lot of therapy. Therapy helped me understand that words can hit as hard as fists, and I’d hurt my family deeply with my words and toxic behavior. I went to Rebecca at last and said, “I want to start over. I want to change.” I got on my knees. “I’m sorry. I had it all wrong.” Then, humbly and sincerely, I asked her for forgiveness.

For most of my life, something like that would have been an unbearable humiliation. Now I work every day to become a better husband and father. Rebecca and I talk to Jim and Marguerite Reeve often. We call them our spiritual parents. They’ve shown us that a loving marriage starts with God at the center.

I have discovered strength in vulnerability, for who was stronger and yet more vulnerable than Jesus, who loved the poor and weak and defied the Pharisees. Who sacrificed his earthly life so we could live with him in heaven. What requires more vulnerability than to forgive and be forgiven? Well, I’m working on that.

In the meantime, I remember that love conquers fear—always—and that to be a man means accepting myself, weaknesses and all. That’s my true superpower.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.