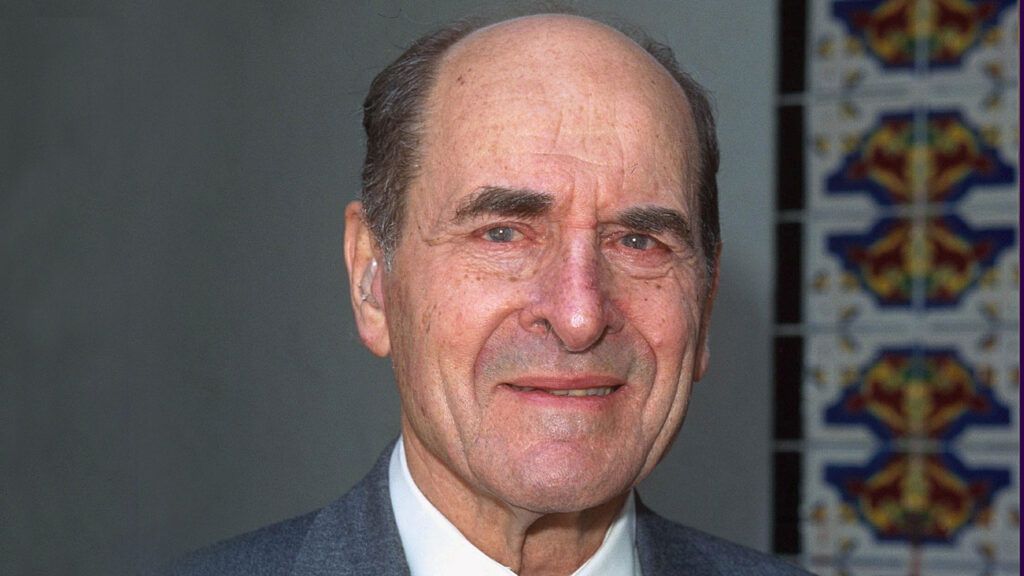

Today in restaurants diners see something that is almost as universal as a menu: a set of emergency instructions on how to clear the airway of a choking victim. It’s called the Heimlich maneuver, named after me for the work I did developing this simple technique that enables virtually anyone to save another person’s life using only one’s hands.

On a quiet Sunday afternoon in 1972 I was at home in Cincinnati reading The New York Times Magazine when I came across a startling article stating that the sixth leading cause of accidental death in the U.S. was people choking on food or other objects. I was appalled at the toll—as many as 3,000 deaths a year, a large number of them children, and many of them, I suspected, preventable. How could this be?

My question was answered when I looked into the standard first-aid recommendations: a slap on the back and a finger down the throat. No wonder so many were dying! I am a surgeon who specializes in problems with the esophagus and swallowing (people choke when something accidentally goes into the windpipe instead of the esophagus); from experience I knew these measures would only lodge the obstruction farther down the windpipe.

READ MORE: A DOCTOR’S LEAP OF FAITH

Time was also critical. A choking victim loses consciousness in three minutes and dies after four. I made a vow right then to help find a way to save these lives. The method had to be so simple that anyone could perform it.

Though it seemed like a solvable problem, I could not know what difficulties lay ahead. But even if I had, I don’t think I’d have been surprised. I have run into challenges most of my professional life.

I remember as a young Navy surgeon in World War II, I was assigned to a covert unit of 12 sailors and marines, code-named “The Apostles,” working behind enemy lines with Chinese guerrilla fighters in the Gobi Desert. The local peasants, suspicious of modern medicine, shied away from our mud-hut headquarters. I felt frustrated as I watched people suffering from treatable infections and diseases.

Then one afternoon a desperate father rushed in carrying his 18-year-old daughter. She was barely conscious, and her abdomen was terribly swollen. I knew that if I treated her and she died, our unit would lose face and our mission might be undermined. Yet I knew I could not turn this patient away, especially since her father had overcome his apprehension and brought her to us.

I had had the local coffin maker craft me a wooden operating table that thus far stood unused. Now I gave my patient fluids through a subcutaneous needle and lifted her onto the table. After a spinal anesthetic, I set to work.

As my scalpel lanced her abdomen, the pent-up infection burst free. I shouted with joy because I saw that with proper drainage of the infected area, there was still hope. The daughter survived, and from then on lines of local folk waited at our mud hut for treatment.

One day the father approached me leading a cow, a token of his appreciation. His livelihood, I knew, required the cow for milk and plowing. Yet custom demanded that he make this gesture. To refuse his gift would disgrace him, so, after thanking him profusely, I asked, “Now, would you help me? I don’t know anything about cows. Could you take care of her? I will be much indebted to you.”

He readily agreed. My dilemma was solved and the father’s pride spared. It is the most rewarding fee I ever collected.

What I discovered 30 years later was that finding broad-based approval of a single, standard method for treating choking victims was almost as challenging and as frustrating as convincing primitive people of modern medicine’s benefits.

First came perfecting the technique. There is always air remaining in the lungs even after we breathe out. Could the lungs be compressed to force that residual air up through the windpipe to expel an obstruction—the way air pressure inside a bottle pops the cork?

The best way to do this would be by applying quick upward pressure just below the diaphragm and rib cage. This would lift the diaphragm, compress the lower part of the lungs, and force the air up and out, like a bellows.

The most practical way to apply that pressure would be for the rescuer to stand behind the choking victim, wrap his arms around the victim’s waist and make a fist. Then he would place the thumb side of the fist against the victim’s abdomen, between the rib cage and navel, grasp the fist with the other hand and press into the abdomen with a quick inward and upward thrust, repeating until the obstructing object was expelled.

If the victim was alone, he could do this with his own hands, or push his upper abdomen against a solid horizontal object, like the back of a chair.

After testing this maneuver I sent an explanatory paper to Arthur Snider, science editor of the Chicago Daily News, and he wrote about it in his column, which was syndicated in hundreds of newspapers nationally.One week after the column appeared, a physician friend sent me a letter enclosing a front-page story from the Seattle Times about a 70-year-old man whose neighbor ran from his house screaming for help.

The elderly man dashed next door and saw the wife unconscious next to a plate of food. He had read Snider’s column and quickly performed the maneuver. A piece of chicken that had lodged in her windpipe popped out and she regained consciousness. The technique had saved its first life!

Reports started coming in from around the country. The most gratifying thing about it all was that often the rescuer was a person with no training in emergency medical procedures. This was something ordinary people could do. The Journal of the American Medical Association called my method the Heimlich maneuver.

Not all the reaction was good. A national organization and highly respected authority on first aid would not, at first, endorse the maneuver. Their officials finally advocated the Heimlich maneuver after four back slaps.

Alarmed by the potentially deadly slaps, I refused to allow my name to be used. Instead the organization used the phrase “abdominal thrust,” a dangerous description because it implied pressing anywhere on the abdomen, which can injure internal organs, especially in children.

I persisted in advocating the maneuver. It was a long, hard struggle, but gradually people became familiar with it. In 1985, then U.S. Surgeon General Dr. C. Everett Koop called it the best rescue technique for choking, and urged that it be used to the exclusion of all other methods.

READ MORE: HER DREAM LED TO THE RIGHT DOCTOR

The Heimlich maneuver has since become standard with first-aid authorities throughout the world. It is also recommended for drowning victims, since it forces water out of the lungs. Reports of drowning victims being saved by the Heimlich maneuver now appear regularly.

Since 1975 the maneuver has saved at least 50,000 lives, among them President Ronald Reagan, former New York City Mayor Ed Koch, and actress Elizabeth Taylor. A few years ago I read of a five-year-old boy in Massachusetts who saved a playmate’s life after having seen the maneuver performed on television. That made all of the obstacles getting the maneuver accepted well worth the struggle.

I have discovered that teaching one lifesaving method to millions of people saves more lives than a lifetime in the operating room. Does God put challenges before us in life? Yes, and unexpected rewards too. How else can I explain the course my life as a physician has taken? Or that I once owned title to a cow in the Gobi desert?

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.