The night I had the dream began like most nights—with me lying awake on my prison cot, each excruciating detail of my arrest and sentencing running through my head. It had been years since I’d been convicted for a crime I did not commit, but the entire ordeal was still fresh in my mind. As soon as I lay down in my cell to try to sleep, the replay would begin. This particular night started out no differently….

August 1984. It happened so early that the sun hadn’t yet risen. Violent pounding on the front door woke me. I stumbled toward it, half-awake. I opened the door, instantly blinded by flashlight beams. “Step outside, Mr. Bloodsworth!” someone shouted. What on earth? My eyes ached as they adjusted to the light. I was surrounded by a group of police officers with guns drawn and pointed at me. “You’re under arrest for the murder of Dawn Hamilton.”

A nine-year-old girl’s brutalized body had been found in the woods behind a mall. Authorities received an anonymous phone call from someone who said I matched the police sketch of the man spotted near the scene of the crime.

I looked nothing like this sketch. The suspect was described as more than six-foot-five, skinny, with curly blond hair and a bushy mustache. I was a six-foot, 200-pound, clean-shaven former Marine who had bright red hair and no prior arrests. But those things didn’t seem to matter. Neither did the fact that no physical evidence linked me to the crime scene. In court, five people testified that it was me that they’d seen. They were sure I had murdered that poor little girl.

When the judge read the verdict in March 1985 and the handcuffs snapped closed around my wrists, I was in shock. The word guilty was like a punch to the gut. At 24 years old, I had been sentenced to death. What made it all worse was that I knew it wasn’t just me who’d been wronged. Dawn Hamilton’s family members hadn’t gotten the justice they deserved. The real perpetrator was out there somewhere and could still hurt others. It made me sick. None of it felt real. This was a mistake, and someone would realize it—wouldn’t they? But weeks turned into months, and months into years, and no one had….

These were the kinds of thoughts that visited me in prison every night, making it hard for me to sleep. I tossed and turned in my bunk. I don’t know when I fell asleep, but suddenly I was dreaming.

In my dream, the door to my cell swung open. In walked a man. He was someone I knew of but had never met before. Why is he so familiar? Then it hit me. It was Pete Rozelle, the then–commissioner of the National Football League. He walked toward me and stood next to my bunk. Without saying a word, he reached into his pocket and pulled out a small object. He took my hand and placed the object—cool, shimmering, heavy—in it. A ring, similar to the kind that football players get when they win the Super Bowl but of a slightly different design.

“This is for you,” Mr. Rozelle said. “This is your Super Bowl.”

“I don’t understand,” I said. He just smiled. Then I woke up.

What a strange dream, I thought, blinking up at the ceiling of my cell. I couldn’t make sense of it. I didn’t even follow football! But the bizarre dream left me strangely hopeful. Hope is a rare commodity in prison, especially on death row, so I clung to the dream, even though I didn’t fully understand it.

It gave me extra motivation to continue working on my appeal. I couldn’t fathom how an innocent man could be locked up and sentenced on such flimsy circumstantial evidence. That was a big part of my defense when the case went back to trial. My death penalty was overturned, but I still faced two life sentences—a life behind bars.

I tried to make the best of it. Once off death row, I was given more liberties. I became a prison librarian. I helped other prisoners find books and spent a lot of time reading. I’d been locked up for four years when I came across a book about advancements in DNA testing. In 1992, the prosecution finally agreed to test the evidence from the case. At this point, my quest felt naive, but I still had hope.

Then my mom, who’d been a source of strength for me throughout my time in prison, passed away. I was allowed to attend the wake for five minutes in handcuffs and shackles, flanked by two armed guards. I felt more trapped than ever. Yet even then in the back of my mind was that dream. If my Super Bowl was meant to be a victory for me—my freedom—then was it on its way?

I had no idea what lay just around the corner. The DNA evidence was in, and I was granted a retrial. On my day in court, I knew that this was the moment I’d been waiting for. Sure enough, my DNA was not a match for any of the DNA found at the scene. Hearing those words aloud, I was so overcome with emotion that I nearly collapsed. Finally the world saw what I’d always known: I was innocent.

On June 28, 1993, after eight years, 10 months and 19 days, I walked out of the prison gates a free man. I was the first U.S. death row prisoner to be cleared by DNA evidence. I was granted a full pardon.

The DNA from the crime scene was eventually matched to the true culprit, a man named Kimberly Ruffner. He was already serving time for assault…in the same prison I’d been housed. I actually knew him. I’d helped him check out books from the library. How could he look me in the eye, knowing I was being punished for the horrific crime he committed?

It was one of the things that I struggled with as I adjusted to life back on the outside. My family wanted everything to go back to normal, but I wasn’t even sure I knew what normal was anymore. I’d spent nearly a decade behind bars. I was a different man from the one who’d been arrested all those years ago.

Since my release, I’ve devoted my life to helping others in similar situations. I work with the Innocence Project, a nonprofit organization that helps exonerate wrongfully convicted people. I found purpose speaking at Innocence Project events, making the case for changes in legislation. Later I also became the executive director for Witness to Innocence—an organization comprised of death row exonerees—to help end capital punishment.

In the quiet moments shortly after I was freed, memories from behind bars haunted me. I still had trouble sleeping. I was painfully restless if I had free time. I couldn’t find anything to ease my mind. One weekend, I had no speaking engagements or meetings. I was filled with dread at the thought of 48 hours with nothing but my own thoughts to occupy me. My girlfriend at the time was working on handmade bracelets for her friends and family, so I offered to help. Over the next week, I made some 50 bracelets. The work soothed my mind and soul.

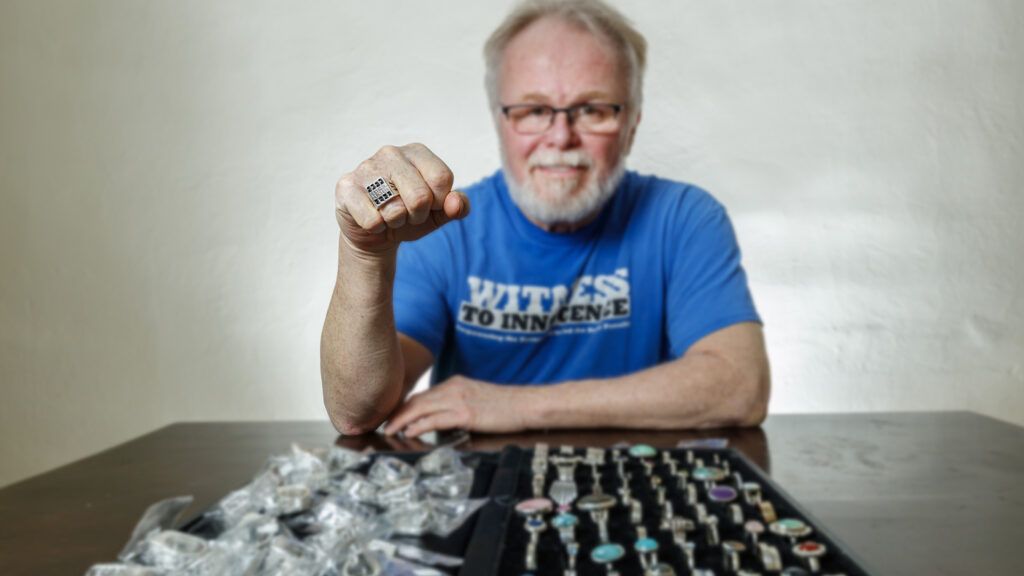

Eventually, I moved on to making rings. I went online and learned how to make simple metal bands out of spare quarters. Eager to learn more, I enrolled in jewelry-making classes at a local college. One of the assignments was to design a ring of our own. I sat down with a piece of paper and a pen and sketched feverishly. It felt as if the ring drew itself. I could not believe what I’d created. The sketch was not of just any ring. It was the ring! The one Mr. Rozelle had handed me in my dream all those years ago.

It resembled a Super Bowl ring but, instead of a team logo, featured an empty cell with the doors wide open. Above the doors was the word Exoneree. The sketch included a teardrop, representing the wrongful conviction, and three drops of blood—small rubies—signifying the past, present and future. The final product was cast in 28 grams of silver.

When I first slipped the ring on my finger, peace washed over me. Here was my reminder of what I’d gone through. A reminder that my fight had been worth it. That even though sometimes it might feel as if I’d walked away with nothing in return for those stolen years, I was in fact victorious. I’d come out the other side with my freedom. I’d wear the ring proudly to remind myself of my victory. Just as NFL players wear their rings to remind them of theirs.

From that original master, I’ve cast more than 230 exoneree rings. I give them, free of charge, to people like me. To innocent men and women who have had to pay for someone else’s crime and left prison scarred, with nothing to show for it. My ultimate goal is to give a ring to every exoneree. I want them to have the gift that my strange dream gave me all those years ago: hope.