The Robson Valley, where I live in the Canadian Rockies, is a magnificent landscape of snow-clad peaks, forested mountains, ranches and farms. The area is a magnet for hikers, snowmobilers and horseback riders.

But this can also be a difficult place to live, and not only because of the winters, when temperatures plummet below freezing and more than 30 feet of snow falls on the highest peaks.

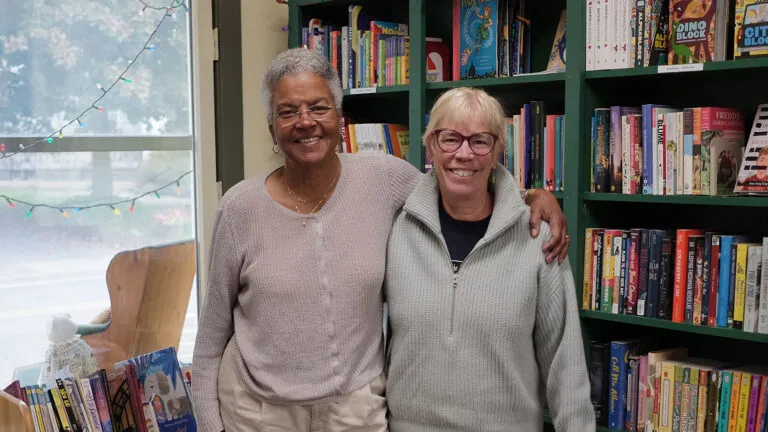

The valley is isolated—we’re six hours by car from Edmonton, nine hours from Vancouver—and many of us like it that way. Lots of rugged individualists up here, from old hippies to mountain men. We come together for community festivals, and neighbors drop everything to help neighbors in trouble.

But after living here 11 years, running an 80-acre horse ranch, I’m still amazed how many people I’ve never met. It’s a delicate balance between sticking together and respecting each other’s space.

That all changed dramatically one recent winter when I got a call from my best friend, Monika Brown, a horse owner like me.

“Two horses are trapped on Mount Renshaw,” Monika told me, sounding agitated. “Reg Marek said some snowmobilers spotted the horses high on the peak. They’re snowbound and starving.”

Reg Marek was a brand inspector from the town of McBride, a rancher who kept track of cattle sales. He was a solid, trustworthy man.

“How on earth did two horses get up there this time of year?” I asked. It was December 9. Snow had been falling on Mount Renshaw, a 7,000-foot peak towering over the Robson Valley, for a couple of months. The slopes were impassible.

“I don’t know,” said Monika. “But someone needs to get those horses down. They’ll die up there.” She hung up saying she’d try to find out more. I spent the rest of the evening fretting.

I’ve loved horses since I was a girl. The thought of two horses doomed to freeze to death on a mountain was too much to bear.

What I didn’t know was that three months earlier a lawyer from Edmonton had taken two draft crosses, which are large, muscular horses sometimes used as pack animals, on a backcountry trip up Mount Renshaw.

The lawyer fancied himself a cowboy, but in fact this was his first time using packhorses on the rugged west side of the Rocky Mountains. He got lost and led Belle and Sundance, a three-year-old bay mare and a 14-year-old sorrel gelding, into a bog.

He freed the horses but Belle and Sundance had lost trust in him and refused to follow. The lawyer abandoned them and rode out on his saddle horse. For the rest of that fall Belle and Sundance roamed the slopes, nibbling grass.

Then winter arrived.

I didn’t have a snowmobile or even know how to drive one. Monika and her husband, Tim, tried to find the horses on a rented snowmobile but they were turned back by heavy drifts. The next day a blizzard moved in. I grieved, figuring that was the end.

Then, on December 15, search and rescue crewmembers looking for abandoned snowmobiles came across two horses trapped in six feet of snow. The horses were so emaciated they looked like skeletons. But they were alive.

I was writing Christmas cards when Monika called. “They’re alive!” she cried. “Leif and Logan with search and rescue found them. They know where they are.”

I jumped up. “We’ve got to get up there. They need someone who knows horses to look at them and feed them. I’ll get in touch with my friends Sara and Matt. Matt’s an amazing snowmobiler. If anyone can get up there he can.”

Matt agreed right away to go up the mountain with Leif and Logan to see to the horses. But my hopes of going up myself were dashed—the blizzard made the snow too treacherous for inexperienced riders.

I told Matt to take a bale of hay and gave him detailed instructions for how to feed the horses—not too much or their digestive systems might seize up—and how to determine whether the horses still had a chance to live.

“And if they don’t?” Matt asked.

I paused. “Someone will have to put them down.”

The day dragged on while I waited for word from the riders. I called the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. Technically it’s a crime to abandon an animal where it might die. The RCMP promised to try to track down the horses’ owner.

Finally, as the sun was setting, I got an e-mail. Matt and the others had found them. They did not have to be put down and they had eaten some hay. I was overjoyed.

But now we faced an even bigger challenge. The horses were miles from the nearest road. Snowmobilers routinely got lost or even died under avalanches in the backcountry.

Somehow we had to rally our far-flung community of farmers, ranchers, snowmobilers and mountain men to get two horses out of treacherous terrain before another blizzard arrived.

The next day I was stuck at home with chores. Horses are remarkable survivors. They grow winter coats and, as long as they’re fed, can survive temperatures 40 degrees below zero or even colder.

Which meant I had to keep my own horses fed and tended as a cold snap moved in behind the blizzard.

At last, on Thursday, December 18, the day dawned clear and Matt said I could accompany him up the mountain.

I woke up extra early, fed my horses and pulled on as many layers as I could—socks, long underwear, fleece pants, a turtleneck, two fleece sweaters, a neck warmer, jogging pants and insulated bib overalls, plus gloves, mitts, hats, a pair of winter boots and an oilskin coat.

We met at a parking lot at the base of a logging road. Over the past few days I’d asked everyone I could think of for help. And Matt and the others had devised a plan to dig a trench from the horses to a logging road, where we could walk them down the mountain. Just a handful of people waited at the lot.

We boarded snowmobiles and set off. The frigid air seemed to knife through all my layers of clothes.

Part of the time Matt stood behind me on the snowmobile, reaching over my shoulders to grab the controls. “Keeps us balanced so we don’t sink into the powder,” he explained over the engine’s whine. At last we arrived. I pried myself from the seat and stumbled down a steep slope.

And there they were. The mare, Belle, had a lovely white star-shaped patch on her forehead. Much of the rest of her hair was gone, probably rubbed away by the snow. The gelding, Sundance, stood with his body against Belle’s, doing his best to keep her warm.

Both horses looked surprisingly alert, their ears pricking.

“Hi, guys,” I said. I covered them with blankets and fed them some hay. Then we spent the rest of the day digging. We made a trench a few dozen meters long.

At this rate it would take weeks to reach the logging road, about a kilometer (.6 miles) away. A storm could blow up anytime. We needed more diggers.

The next few days were discouraging. I sent out more e-mails, made more phone calls, even got some media coverage. We set up a command center of sorts at a snowmobile shop in McBride.

Each morning, though, the same small number gathered at the parking lot. The trench lengthened, but not enough. I got frustrated. Once I even lit into a group of snowmobilers massing for a day of carving up the mountain.

“Two horses are going to freeze to death up there if you don’t help us dig!” I cried. The snowmobilers made vague promises to help but we never saw them.

Please, I prayed in desperation one night, don’t let these horses die.

The very next day something amazing happened. Just when I thought the clear weather couldn’t last, help arrived. The media coverage fed on itself until suddenly CTV, the national broadcaster, was covering the rescue effort.

People from every part of the Robson Valley began turning up to dig. Snowmobilers, oil rig workers, ranchers, farmers, everyone grabbed a shovel, boarded a snowmobile and headed up the mountain. The temperature dropped to 40 below zero and still people came.

Two days before Christmas, 24 people showed up to dig. At 1:30 that afternoon, under brilliant mountain sunshine, the trench was completed. We walked Belle and Sundance to the logging road, then almost 30 grueling kilometers (18.6 miles) to the parking lot.

We arrived at 10:00 p.m., frozen to the bone. Ray Long, a Robson Valley rancher, met us with a stock trailer and drove the horses to his farm. Ray had provided the hay they had been eating.

There is much more to Belle and Sundance’s story—how, with the help of the SPCA, the horses found new homes on ranches in British Columbia, and their former owner was charged with animal mistreatment and ordered to pay a fine.

What stands out for me is that last day of digging, when it seemed like the entire Robson Valley was on the horses’ side. People I’d never met before dug snow, drove snowmobiles, made sandwiches and coffee, talked to the media and kept the rescue effort going. A community of individualists came together as one.

I didn’t adopt Belle or Sundance, but Belle’s new owner sent her to me for saddle training. The trailer pulled up and out came a horse I barely recognized, healthy and glossy with strong, defined muscles, standing quiet and alert.

I put my hand on her neck. We saved you, girl, I thought. And then I realized Belle and Sundance had saved us too. Coming together as one—it was the best Christmas gift our beautiful, isolated valley could have asked for.