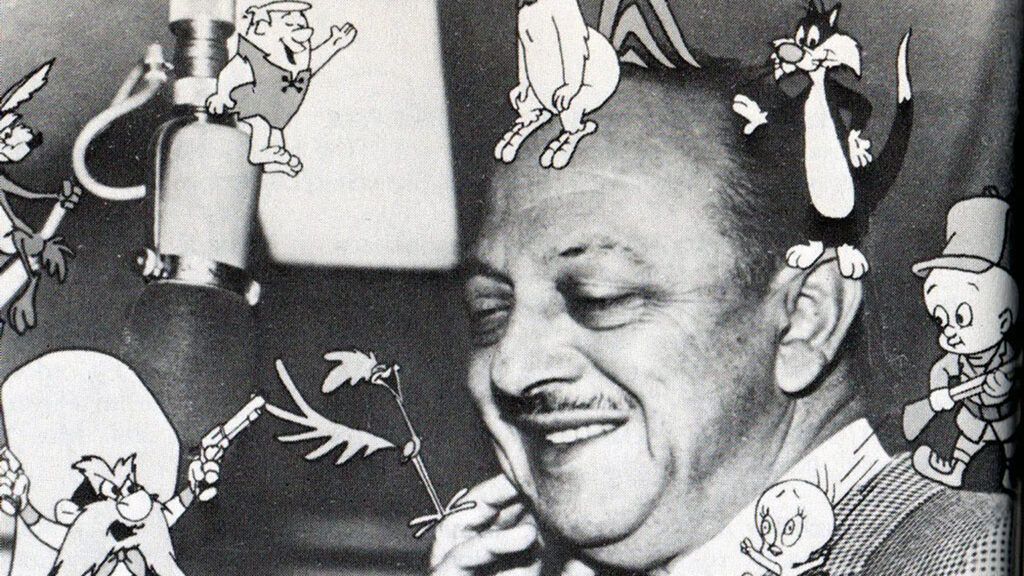

In Hollywood, they tell me, I’m known as “the man of a thousand voices.” Like most Hollywood labels, this is an exaggeration, but where voices are concerned I do have quite a few. When you hear Barney Rubble’s gravelly tones in The Flintstones on television, that’s me.

Such cartoon characters as Bugs Bunny, Daffy Duck, Woody Woodpecker, Porky Pig, Sylvester Cat and Tweedy are all close friends of mine for the very good reason that they have to borrow my vocal chords before they can say anything.

It’s one of those slightly zany jobs that are good fun, pay well and bring other people innocent pleasure, and I wouldn’t change it for the world.

But a few years back the man of a thousand voices found himself listening to one small voice that he had never paid much attention to before. The voice was inside him.

I believe this same small voice is inside every one of us, but we’re too busy or preoccupied or self-satisfied to listen. Sometimes it takes a terrific jolt, and the silence that follows that kind of jolt, before the voice can make itself heard.

In my case, the jolt was nearly fatal. One night as I was hugging a curve in my little sports car, an automobile coming the other way went out of control. There was a head-on collision at a combined speed of about 90 miles per hour.

When they pried what was left of me out of the wreckage and rushed me to the hospital, they found that the only bone in my body that wasn’t broken was my left arm.

When I finally came out of the fog of anesthesia, back to a world of pain, the first thing I saw was Jack Benny sitting by my bed, looking miserable. I had worked with Jack for years; we were close friends.

I summoned all my strength and whispered, “I’m going to make it, Jack.” He said, “You’ll have to make it, because I can’t do my show without you.” I was too weak even to try to reply, but he saw the glitter of tears in my eyes, and knew that I understood.

In the weeks that followed, I think I survived chiefly on the power of prayer—other people’s prayers. I had never realized how much goodwill my cartoon characters had built up for me.

Hundreds of letters came from all over the world with prayers for my recovery. They came from Catholics, Protestants, Jews—even from Buddhists and Mohammedans. Children sent cards and coins and their favorite toys.

It was like being supported and sustained by a great flood tide of affection, of concern, of love. I’m convinced that it helped my shattered body begin to slowly heal itself. I also think it enveloped me in a kind of serenity that made it possible for me to hear a small, quiet, inner voice.

This voice did not speak to me in words; it was more like a sudden awareness of truths that had been around me all the time, truths that I had been too impatient and too self-centered to see.

For example, I had always taken my talent for voice characterizations pretty much for granted. After all, I had been using it for fun ever since grammar school, and professionally since 1938 when I signed a contract with Warner Brothers to do multiple voices on ‘Bugs Bunny’ cartoons.

But now I began to realize that talent is a gift, a gift that can be withdrawn at any time, an unmerited gift that can be repaid only by a sense of constant, humble gratitude to the Giver.

Another awareness was of a quiet but mighty undercurrent of justice that runs through human affairs. I began to see that the universe really is an echo chamber, where sooner or later the thoughts you have and the deeds you do are reflected back to you.

For example, some years before my accident, a friend of mine named Harry Lange had a heart attack while playing the part of Pancho in “The Cisco Kid.”

I offered to fill in for him for quite a long time—26 weeks, I think it was—and so during this period the studio was able to keep on sending his pay check to his wife.

Now, suddenly, the tables were turned; I was the one who was incapacitated. But like an echo, out of the past came an offer from Shep Menkin, a talented friend of mine: “Let me do your voices while you’re laid up; I’ll make sure that your family gets the money.”

As it turned out, I didn’t have to take Shep up on his offer.

For a whole year I remained immobilized in a full cast, but thanks to the devotion of my family, and the ingenuity of my wife who turned our home into a combined sanitarium and recording studio, I was able to make the sound tracks that kept 125 people at Warner’s working full-time.

I learned, too, during the long, slow period of recovery that pain is a solvent for all sorts of negative things. Antagonisms, for example.

There was one associate of mine whom I’d never liked; I thought him arrogant and conceited, and I’m afraid I showed my dislike rather plainly.

But when I met him again during my convalescence, my inner voice whispered to me that the main thing wrong with this man was that he was reacting to the hostility in me. So I told him frankly that I had misjudged him, that I was sorry, and that I hoped we could be friends.

His first reaction was one of amazement. His next reaction was one of warmth and self-accusation. Thus I learned that it is really quite easy to turn an enemy into a friend.

But the most valuable single thing that my inner voice taught me was the importance of expressing affection.

I don’t think that before my accident I was any more remiss than most people in this regard. But lying there in my cast, I recalled how my efforts in the past to tell people that I was grateful for their friendship, or to thank them for caring about me, seemed hopelessly inadequate.

And so I began to make a deliberate effort to set this right. To Jack Benny I said, “I want you to know how much I admire and appreciate and love you. I want you to know how much your friendship means to me. I’m grateful that my life has been spared so that I can tell you these things.”

I expressed such feelings to other people too. Maybe they were a little startled, or even momentarily embarrassed. But every time, I’d feel a surge of warmth and closeness that strengthened the bond between us.

Today I walk with a cane, but that’s a minor matter to a man who has spent a year in a cast. I go on participating, invisibly, in a lot of activity designed to bring joy and happiness to youngsters and young-oldsters.

Sometimes I’m the chirp of the pet dinosaur in the Flintstone Family, sometimes I’m the hiccough of a Disney cat. But believe me, I’m a happy hiccough and a cheerful chirp, because I’ve discovered that the more you express affection, the more you have to express, and the more comes back to you.

You don’t have to wait until you’re at death’s door to learn this, you know. Anyone can be a man or a woman of a thousand voices too. Because there are at least a thousand ways to say, “I love you”… and all of them are good.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.