In many ways, 1996 was the worst and the best year of my life. My dad was dying of cancer. And that September, Bill Monroe passed on. People call him the “Father of Bluegrass,” and I’d always thought of him as my musical father. Two men who had been my foundation in life. And I was losing both of them.

Mr. Monroe’s state funeral was held at Nashville’s Ryman Auditorium, the historic home of the Grand Ole Opry. Mandolin in hand and heart in my throat, I took the stage with musicians Vince Gill, Marty Stuart, Roy Husky, Jr., and Stuart Duncan. Looking back at us was a sea of country music royalty. On the stage next to us, Mr. Monroe’s mandolin stood on a pedestal, lit from above. I turned to the other musicians, gave them a nod, and we started playing.

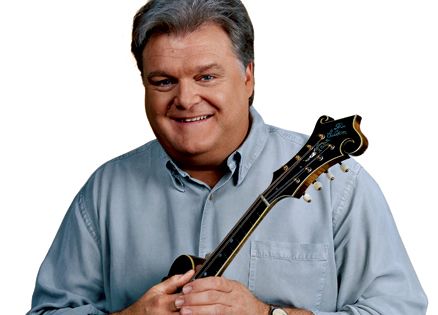

Bluegrass is my life. In the little mountain town of Cordell, Kentucky, where I grew up, I heard bluegrass and gospel music every day, either played live or on the big clunky 78s my parents liked to spin in our living room at the end of the day. I was singing in church by age three. Dad bought me my first mandolin when I turned five. I learned how to play it, and on weekends I’d bring it down to the town grocery store. I’d sit on the counter next to the Coca-Cola cooler and pick away. Folks would clap and throw me change—nickels, dimes, even a quarter now and then. The money was handy, but I’d have played if there weren’t a soul around. The music fed something deep inside me.

I was six when Bill Monroe came to town to perform. It’s hard to describe the kind of figure Mr. Monroe cut in the eyes of a small Kentucky hill town like ours in 1960. Mr. Monroe wasn’t just a famous singer like Elvis. He was a famous singer who sang our music. Pure. Simple. Straight from the heart. Just the way you’d hear it played on a front porch or at a church meeting. Mr. Monroe came from country stock himself, and he’d gone out into the world without changing to suit anybody. When he played in towns like ours, he was welcomed like a returning hero.

Mr. Monroe was a couple of songs into the concert when some people who knew me from the grocery started yelling out my name. Finally, he finished a song, looked out at the crowd, and said, “Wherever you are, Ricky, you better get up here. Sounds like folks want to hear you play.”

I don’t think I even had time to feel nervous. I jumped off my dad’s lap and made my way toward the front of the auditorium. Mr. Monroe reached down and pulled me onto the stage with him.

“What do you play, son?” he said, his eyes twinkling.

“The mandolin, sir,” I managed to say.

Mr. Monroe slid his own mandolin off and held it out to me. I stood there, open-mouthed with awe. Bill Monroe’s mandolin. He slipped the strap over my shoulder. “Okay, son,” he said, adjusting the strap. “Let’s hear some music.”

I started picking a bluegrass hit called “Ruby” and the crowd went wild, clapping and hollering for their hometown kid. I finished the song and Mr. Monroe gave me a nod. He took the mandolin off my shoulder, picked me up and set me back on the ground. I felt like my feet had just hit earth after a trip to heaven.

Folks would bring up that day for years afterward. “You’re the young fellow who played Bill Monroe’s mandolin,” someone would inevitably say at a church social or fair where I was playing. I’d nod my head and feel a sense of pride. Not cocky pride, but the good kind. The kind that comes when you’re doing what you believe God wants you to be doing. And God wanted me to play bluegrass. There was no doubt in my mind about that. Why else would he put such a desire in my heart?

I graduated from high school and played bluegrass full-time with another legendary figure, Ralph Stanley. Every now and then we’d run into Mr. Monroe at a bluegrass festival. Sometimes he’d ask me to get up and play with him. I’d go back to that day when I was six and he had strapped his mandolin onto me. He’d done more than just give a young boy the thrill of his life that day. He’d passed something on. Something strong and vital and meaningful, something I feel every time I pick up my mandolin.

In 1981 I moved to Nashville, my sights set on a record deal. It wasn’t long before I got one. The album wasn’t straight bluegrass. It couldn’t be if I expected it to sell. “Bluegrass is great stuff,” Nashville agents and promoters said. “But it doesn’t have enough excitement, enough crowd appeal.”

Excitement? To my mind, nothing in popular country had the fire of a real down-home bluegrass session. But I needed to move records, so I kept my sound popular enough that the record company and the radio stations were happy.

I enjoyed some great commercial success in mainstream country, but I still managed to play pure bluegrass with Mr. Monroe. Either I’d call him to the stage at a gig I was playing, or he’d call me up at one of his—it didn’t much matter.

Every now and then Mr. Monroe and my dad would ask, “Ricky, when you gonna make a bluegrass album? A real one, through and through?”

I’d always give them the same answer. “When the time is right, I will.”

In the mid nineties, Mr. Monroe’s heart started to give out. After he had bypass surgery, I visited him at least once a week while he recovered in a nursing home. Sometimes on those visits, we wouldn’t say 10 words. Mr. Monroe would reach for a mandolin that was always set close by his bed right next to his Bible and start picking out a tune. Then he’d hand the mandolin to me and I’d pick a tune. Time went right out the window. We’d play for three or four hours until the nurses said visiting hours were up.

Mr. Monroe passed on a few weeks later. I was as heartbroken as I’d ever been. With Mr. Monroe gone, my path in life now seemed unclear. On top of that, country music was changing. Videos were becoming more important. The music itself was taking a backseat to gloss and image.

Record sales were everything. Tradition? That seemed to have been forgotten. And the more things changed the more old-fashioned I felt, trying to keep up with something I didn’t necessarily believe in. Lord, I wondered, who am I?

That was how I was feeling that day onstage at the Ryman Auditorium for Mr. Monroe’s funeral. I counted off and me and the boys kicked into a full-on version of “Rawhide,” Bill Monroe-style. Just like that the music took over, the way it always did. Raw music, pure and rich, as big and deep as the country that created it. Then, in that glorious tapestry of sound, I heard Mr. Monroe again, alive as ever, living and breathing in the music that was his soul. It was part of my soul too. Always had been. I thought back to my dad and Mr. Monroe’s question, “When you gonna make a bluegrass album?” The Lord was telling me it was time to use the desire he’d put in my heart.

The crowd was on its feet. The light shone down on Mr. Monroe’s instrument. And I knew I was who I had always been. I was the boy who had played Bill Monroe’s mandolin.