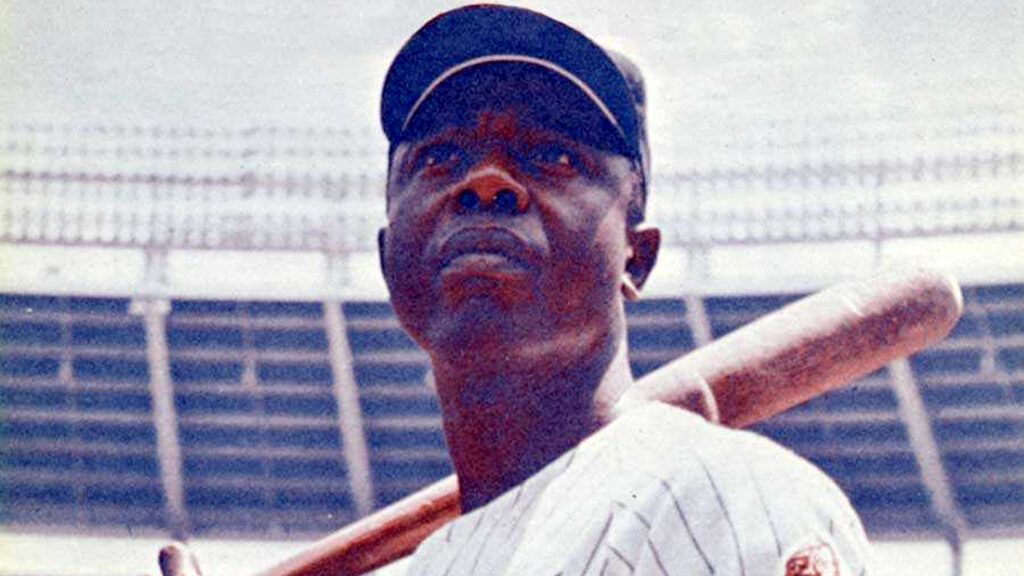

No matter where I go, someone is bound to ask me if I think I will break Babe Ruth’s record of 714 home runs. The Babe is a legend now. He created more excitement than any player who ever lived.

What I find so hard to believe is that Hank Aaron, a nobody from Mobile, Alabama, is really the first player in 40 years to challenge that home-run record. Who am I to be in this position? How did it come about?

Well, I sure didn’t make it on my own. There were a number of people who helped me at crucial times. And because of those people I’ve tried to live my life a certain way during my 21-year career in baseball.

ENJOYING THIS STORY? SUBSCRIBE TO GUIDEPOSTS MAGAZINE!

My parents were strict with us kids. We had rules, we did chores and we all went to the Baptist church every Sunday.

There were plenty of spankings too. When I was 15 I was once offered two dollars to play baseball on Sunday afternoon. I turned it down. I knew Mama would never allow me to play ball on a Sunday.

My father, Herbert Aaron, was a boilermaker’s helper in a ship-building company and worked long hours to feed and clothe his wife and six children. He didn’t have much time to play ball or talk to us, but when he did, it meant something.

Like the time I skipped school to listen to the Brooklyn Dodgers game at the local poolroom. For some reason he got off early that day and saw me there. He didn’t get mad; he just crooked his finger at me to walk home with him.

I thought I was in for it, but my father didn’t punish me. He just asked some questions. Like what I was doing out of school and in a poolroom.

“I was listening to the Dodger game,” I said. “I want to be a baseball player. I’ll learn more about how to play listening to the Dodgers than sitting in a classroom.”

My daddy wasn’t an educated man, but he and my mama had made up their minds that their children were going to get educated. “You don’t think those fellows playing in the big leagues are dumb, do you?” he asked me.

“No, but they didn’t learn to hit and throw in a classroom,” I answered.

“You can be a baseball player and get an education too,” he continued earnestly.

We had an old car that was parked in our yard, and we sat in that car and talked and talked. I told him I was going to drop out of school when I got a chance to play baseball. He turned around and put his hand on my shoulder.

READ MORE: BABE RUTH ON THE FOUNDATION OF FAITH

“Son, I quit school because I had to go to work to make a living. You don’t have to. I put fifty cents on that dresser each morning for you to take to school to buy your lunch and whatever else you need. I only take twenty-five cents to work with me. It’s worth more to me that you get an education than it is for me to eat. So let’s hear no more about dropping out of school.”

You don’t forget this kind of sacrifice by your father. Herbert Aaron was always ready to deny himself something if it would help his family.

When I was 17 I was offered $200 a month to play ball for the all-black Indianapolis Clowns. I could hardly believe it. That kind of money for a game you loved! Only when I promised to continue my education later (which I did) were my parents willing to let me accept the offer.

So one day in May, 1952, my mother, two of my sisters and a brother took me to the Mobile railroad station for the trip to Charlotte, North Carolina, to join the Indianapolis team where they were having spring training. I left with two dollars, two sandwiches and two extra pairs of pants. It was while playing with the Clowns that I encountered this fellow by the name of Jenkins.

Jenkins was a pitcher and I roomed with him when we were traveling. He was tall and bony with big eyes and real short hair.

One night I was about to drink a container of milk when a bug flew into it. Disgusted, I poured it out. Jenkins was watching me.

“Aaron, do you know how many people in this world would have given anything for that milk you poured out?”

“There was a bug in it.”

“That doesn’t matter. Waste is a sin. There are too many starving people in this world for us to waste food like that.”

I would get annoyed with Jenkins and his preaching at times. We would get two dollars a day for meal money and when we stopped to eat, Jenkins would buy a few slices of bologna and a loaf of bread. He’d eat the bologna and half the bread and then sell the other half to another player.

Then one day after he received the two dollars for meal money, I saw him put one dollar in an envelope and seal it.

“What are you doing that for?”

“Mailing it to my wife,” he said. “I send her half my meal money every day.”

You know, I’ve never forgotten that tall, bony, unselfish guy. And I’ll think of him at some fancy banquet with all the food going to waste. Or when I’m telling my own kids not to be wasteful. Jenkins, like my father, had that rare quality of self-sacrifice.

I guess if I had real hero-worship for anyone, it would be for Jackie Robinson of the Brooklyn Dodgers. I was about 14 when he became the first black to play in the big leagues. I read everything I could find about him.

What fascinated me so much was that Jackie was an emotional, explosive kind of ballplayer. Yet during that crucial first year in the big leagues, he didn’t lose his temper in spite of a steady barrage of insults from fans and other players.

How did he keep control? I learned later that he prayed a lot for help. And he also had a sense of destiny about what he was doing, so much so that he felt God’s presence with him. He learned to put aside his pride and quick temper for the bigger thing he was doing.

Jackie’s example helped me when I faced a similar situation while playing with Jacksonville, Florida, in the Southern Association back in 1953. Blacks had never played in this league before. Three of us—Horace Garner, Felix Mantilla and myself—were the ones to break the color line.

I’m not the crusader-type, and there were times, frankly, when I wanted out. Like those bus trips from the ball park after each game on the road. The white players were left at the hotel while Horace, Felix and I were taken to a private home.

The best way to lick this racial thing is to play well. Play so well that the fans forget your color. And that’s what happened that year. As one sports writer put it, “Aaron led the league in everything but hotel accommodations.”

You learn a kind of acceptance in a situation like this. You set aside the thing that bugs you so that you can get on with doing what you know you’re supposed to do. I lost my temper a couple of times last spring when some fans heckled me from the stands. Then I’d remember Jackie and what he accomplished with his self-control, and the fact that there will always be people who resent you if you try to climb too high.

I’m not trying to preach a sermon with these stories, but they do add up to something basic which I think has enabled me to play baseball year after year now for 21 years. Like my parents—and Jenkins—and Jackie Robinson and others, I’m learning to do without something I want at the moment—like certain foods, drink and other temptations—to achieve the bigger thing ahead that is really right for me to want.

Certain parts of spring training in recent years have been agony and a punishment that I would have liked to skip. But at my age I have to discipline my body to keep on playing. The home runs keep coming only if my body is fit.

I also know this: I need to depend on Someone who is bigger, stronger and wiser than I am. I don’t do it on my own. God is my strength. He gave me a good body and some talent and the freedom to develop it. He helps me when things go wrong. He forgives me when I fall on my face. He lights the way.

The Lord willing, I’ll set a new home-run record. If I don’t, that’s okay too. I’ve had a wonderful time in baseball and have enough great memories to last two lifetimes. I have been blessed.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.