The movie theater where I saw 42, the film about Jackie Robinson breaking the color barrier in Major League Baseball, was packed with kids. When the lights came up, their eyes were wide.

Black men not allowed to play on the same sports teams as whites? Laws prohibiting blacks and whites from staying in the same hotels? Jackie’s story must have seemed like science fiction to their generation.

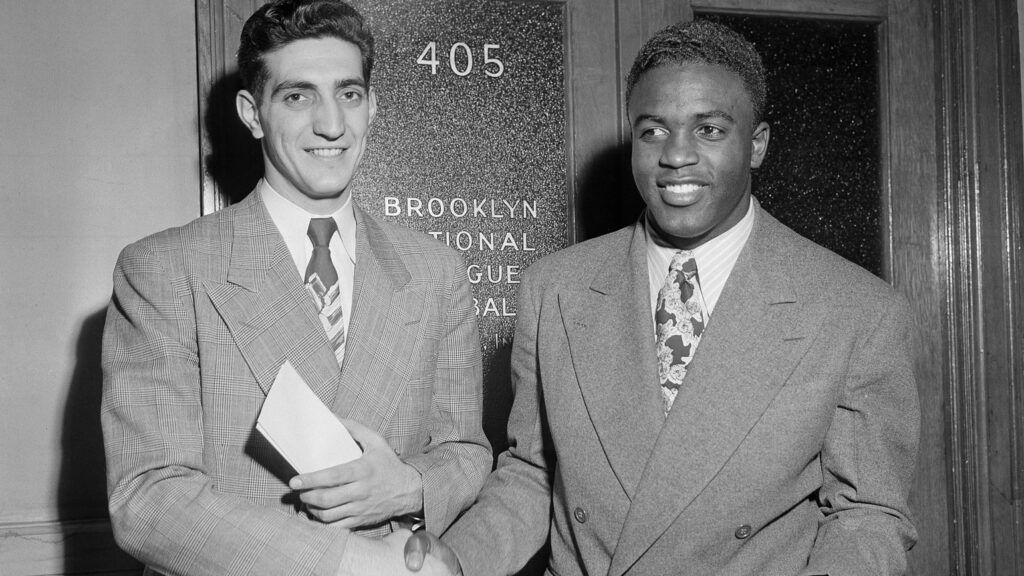

It wasn’t science fiction to me. I was there with him on the 1947 Brooklyn Dodgers. I was a scared 21-year-old pitcher, trying to make it in the majors. Jackie was just doing the same, I thought. Until he walked into the Dodgers clubhouse for the first time that Opening Day.

READ MORE: HANK AARON—GOD IS HIS STRENGTH

I hadn’t thought much about segregation in baseball. Few of us ballplayers did. We were too worried about our own jobs. That’s what my prayers were about. I didn’t want to get sent back down to the minors.

I had heard about Jackie, of course. Everybody on the team had. How big and fast and strong he was. Duke Snider, our future Hall of Fame centerfielder, who grew up near Los Angeles, used to watch Jackie play at UCLA.

“Ralph,” he said, “I saw Jackie run from the baseball field to the track meet, still in his uniform, and broad jump twenty-five feet.” Twenty-five feet was close to the world record. It was as if Jackie could do anything.

I found that out firsthand a few days before Opening Day, when I pitched against him in a preseason exhibition game. I was still working on my stuff, fine-tuning my pitches.

I’ll throw him a fastball, I thought. It was a good one.

Thwack! Home run.

I was from Mount Vernon, New York. I’d grown up playing with black kids. They’d been to my house and I’d been to theirs. Race wasn’t an issue with me. This is a guy who can help us win the pennant, I thought.

When Jackie stepped through the clubhouse door, around 9:30 A.M. on Opening Day, lugging his equipment bag, I was glad to see him. There was only one other player there that early—Gene Hermanski, a reserve outfielder from New Jersey who also had no problem with blacks.

But Jackie didn’t know that. He had heard about a petition that had circulated around the clubhouse. A handful of players said they wouldn’t play with Jackie on the team.

READ MORE: HE CHANGED BASEBALL FOREVER

I didn’t know it then, but the Dodgers’ owner, Branch Rickey, had extracted a solemn promise from Jackie: that no matter what anyone said or did—even his own teammates—he would turn the other cheek. I eyed Hermanski. We could sense what Jackie was thinking: Are these guys friends or foes?

I stood, walked over to him and stuck out my hand. “Welcome aboard,” I said. Hermanski was right behind me. “Hope you have a great year,” he said.

Over the next hour, the rest of the players arrived. Some welcomed him. Others pointedly ignored him. There was no mention of the petition. Rickey had told the players involved that Jackie was staying, and if they didn’t like it, they’d be the ones to go.

But that didn’t change their attitude.

Look at him, I thought, watching Jackie as he quietly dressed in his uniform, number 42. Twenty-four other guys on the team, and not one went to sit with him or offer him intel on Johnny Sain, the great Boston Braves pitcher we’d be facing that day.

Jackie sat on a stool, facing his locker. Around him, the hustle and bustle and chatter of ballplayers readying for a game went on. It was like he was invisible. This was a historic day for baseball, for America, and none of us wanted to talk about what was going on.

I wanted to do something for him. Crack a joke. Show Jackie—and my teammates—that he was a Dodger now, one of us. But I didn’t. I was too scared. Young players like me were supposed to keep their mouths shut.

In four days I’d be getting my first start of the season, against our archrivals, the New York Giants, at their ballpark. The Giants and their fans would get on Jackie, but they’d get on me too. I glanced at Jackie across the locker room.

Maybe life looks pretty good to him right now, I thought. He’s in the big leagues. He’s living his dream. Instead of saying a prayer for him, I said one for me.

READ MORE: DON LARSEN—MY MIRACLE GAME

Twenty-six thousand Brooklyn fans came out that Opening Day. Somehow, in the minutes before we took the field, I ended up sitting beside Jackie in the dugout. He turned to me.

“You know, Ralph,” he said, uncertainly, “this is a big day for me.”

I knew what he meant: It wasn’t a big day just for him, but for all African-Americans. I was a little surprised he was confiding in me.

“Just go out and play your game,” I said. “Don’t change anything. Be your natural self.”

The instant he took the field, though, I saw that wasn’t possible. I saw what he was up against. Everyone in the ballpark zeroed in on him. And not just the fans. The players too. Afterward, one of my teammates came up to me in the clubhouse. “What do you think of Jackie? You think he belongs?”

If guys in our own club don’t believe in him, what will it be like for him when we hit the road? I wondered.

That night I talked to my brother, John, about Jackie. “Jackie’s under a ton of pressure,” I said. John knew what I was really asking—it was the question I kept asking myself. Should I be doing more to help him? It was a question I prayed about.

“You’re under a lot of pressure yourself,” John reminded me.

John was right. If I didn’t pitch well, I’d lose my job. I’d get sent down, maybe never make it back to the majors, my dreams dashed.

Then we hit the road. That’s when it became clear to me that the pressure I felt was nothing compared to what Jackie must have been feeling. Pitchers threw at him—at his head. There were no batting helmets in those days. Runners went out of their way to try to spike him.

In Philadelphia, the Phillies manager, Ben Chapman, shouted from his dugout, “Hey, boy! I need a shine.” On the Dodgers bench, we could see Jackie just burning up inside. But Rickey had made him promise: Turn the other cheek.

No one was holding me back, though, keeping me quiet. Please, God, I prayed, give me the strength to act. But I didn’t. I said nothing. Not even, “Hey, shut up!” None of us did.

READ MORE: THE MANY SIDES TO BRANCH RICKEY

After the Phillies game, in the clubhouse, I went up to Jackie. “Just ignore him,” I said of Chapman. “He’s ignorant.” But the moment had passed.

Every city we traveled to, Jackie was treated the same. The beanballs. The ugly racial slurs. And he just grimaced and took it.

One afternoon, a month into the season, I decided, Enough.

“Jackie, how about having dinner with me?” I asked after a ballgame in Philadelphia. He studied me, to make certain I was serious. A lot of the team socialized off the field. No one had ever invited Jackie.

“Yeah, Ralph, that would be good,” he said.

That night we got a table in our hotel’s restaurant. At first we kept the conversation to the game we’d played that day and our families. It took a while, but I finally got the nerve to ask, “How do you just sit silently and take it?”

READ MORE: HANK AARON ON SACRIFICING FOR OTHERS

He told me the story of his first meeting with Rickey. How Rickey, a devout Methodist, reached for a book titled Life of Christ, by Giovanni Papini, opened it to the passage on the Sermon on the Mount and read it aloud.

“Ralph,” Jackie said, “many nights I get down on my knees and pray to God for the strength not to fight back.”

Playing well, I suddenly understood, was the best strategy. If we started a brawl with every team over Jackie, it would only have made it harder. Turning the other cheek was fighting back.

Jackie hit .297 that year, led us to the World Series and was named Rookie of the Year. But after that night, to me it wasn’t his baseball ability that stood out. It was his strength of character. His faith. What he accomplished that year was the most incredible thing I’ve ever seen in sports.

I don’t know if courage is a quality you can pass along. But I know I drew strength from him that night in Philadelphia. I thought, I’m blessed to be here, to be Jackie’s teammate. To be his friend.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.