I scooted up to my computer desk that April afternoon in 2016 and logged on to Ancestry.com. At 66 years old and retired from my job as an engineer, I figured I could use another hobby besides golf. The previous year, I’d mentioned to my wife, Debbie, that I was curious about my family tree. She’d hopped on that idea (apparently I’m hard to buy for) and given me a DNA kit for Christmas.

I’d sent in a small vial of saliva. The initial results showed I had British and Nordic ancestry. I wasn’t surprised. Dad’s heritage was Scandinavian, and Mom’s was mostly British. Now I had new e-mails, automatically generated, showing who else on Ancestry .com might be related to me. I scrolled through the results.

Most of the people listed were distant relatives—cousins I’d never met who’d also submitted DNA samples. But one message knocked the breath out of me. We have found a very high probability of a father-son relationship between you and Son Vo.

I stared at the monitor and reminded myself to breathe. A name like that could mean only one thing: Vietnam. A time in my life I’d spent the past 46 years trying to forget.

I’d done well enough in high school to earn a scholarship to North Dakota State in the fall of 1967. But I wasn’t mature enough to handle the freedom of being away from home for the first time. I partied too much, studied too little and blew my scholarship. My hardworking parents couldn’t afford to pay for my education.

The draft was in full swing. I thought about signing up. Dad had been a Marine, and I had three uncles who’d served in World War II. A cousin of mine had been killed in Vietnam earlier that year. I could enlist in the Army, then go back to college on the G.I. Bill. If I volunteered to serve in Vietnam, the Army would knock five months off the tour. So in January of 1969, I went to basic training at Fort Lewis, Washington.

I wanted to be on the front lines and thought I’d signed up to be a medic. Somehow I marked the wrong box and ended up as a preventive medicine specialist. I did my advanced training in San Antonio. We flew out to Vietnam in July 1969, the day after Neil Armstrong took his first steps on the moon. My first six months in country, I was assigned to Bien Hoa Air Base. Conditions were usually primitive on the Saigon-area firebases, where the Army set up artillery in the jungle to support infantry patrols. During the rainy season, we tried to make it better for our troops by flying missions to spray the bases for flies, mosquitoes and other disease-carrying insects. I became known as the mosquito man, examining bloodsucking pests in the lab and determining whether they carried malaria. I was proud of the work we did.

Then I was transferred to Long Binh, the main Army post, some 20 miles outside Saigon. My assignment was on the night shift, inspecting retrograde cargo going back to the U.S. I hated it. I felt dead tired all the time, and it was stressful dealing with other soldiers who were dead tired.

News from the States filtered to us troops. We heard about demonstrations and rioting, how so many Americans objected to the war. We soldiers began to feel that people back home didn’t support us or appreciate how we were putting our lives on the line for our country. In my case, depression took hold.

My only escape was Saigon. Sometimes I was lucky enough to make a delivery there. The city was alive. I had every third or fourth weekend off, and my buddies and I would go to our favorite haunts. We blew off steam, drinking, partying, doing our best to try to forget the war.

Thirteen months later, I was back in North Dakota. There was no hero’s welcome at the airport or anywhere else. Dad gave me back my old job as a laborer and truck driver for his house-moving company. After a month, I moved out of my parents’ house so I could be alone. A few months later, I moved away from my hometown altogether. I just didn’t fit in anymore. Being around people made me jumpy. I had panic attacks. Was I losing it?

I’d joined the Army as a confident young man. Watching peace rallies and protesters on the nightly news, I lost my self-assurance, my conviction that I’d done the right thing by enlisting. I’d given up almost two years and risked my life only to discover that the general public thought this was a war we shouldn’t be fighting. My parents and family were proud, but I had a sense that they too wondered if the war was worth the price.

My brother tried to get me to start a band with him. We both sang and played a couple of instruments, a talent that came from our dad, who could play anything with strings. We’d had a band in high school. Now I was too nervous to even get onstage.

Hoping a change of scenery would help, I moved to Kansas to work in the oil fields. I met a woman and we married. I returned to North Dakota State to get a degree in engineering, then landed a job in Alabama, where we settled down. We had four wonderful children, but things fell apart. We divorced after 13 years.

My depression deepened. Suicidal thoughts scared me into seeking help. I was diagnosed with PTSD and got treatment. Slowly I began to feel like myself again. Then, in 1988, I met Debbie. Like me, she was divorced and had children. We fell in love and married. These 28 years I’d had with her and our blended family—my four kids and her two sons—had been the best. I had put Vietnam behind me: a dark, wasted time in my life.

Now a simple DNA test showed I’d left not only memories behind me but a son. I stood up from my computer desk and paced, trying to picture the streets of Saigon, the people I’d met. I’d been only 20 back then and single. So young. So naive. I’d had a few brief relationships. But there was no one whose name or face I could remember.

I found Debbie in the kitchen. “You need to see this e-mail I got from the ancestry site.”

I sat at my computer desk again, Debbie peering over my shoulder.

“How do you feel about it, Bob?” she whispered.

I was an engineer. I trusted science. “DNA doesn’t lie.”

We looked up the name Son Vo on Facebook. There were several. A 45-year-old professional musician in California caught my eye. Is that him? I stared at the profile photo of a dark-haired man on stage with a guitar. I checked the birthday listed on his page. He was born in 1971, five months after I’d come home. It was entirely possible he was my son. But how did he end up in the U.S.?

My mind swirled with questions. Should I contact him? He would have gotten the same automatically generated e-mail that I did about a father/son connection. Had he looked me up on Facebook too? Did he want to meet? To have a relationship? Was he angry? Would he understand about the circumstances, that I didn’t even know I’d gotten someone pregnant?

Debbie and I talked about it. We decided to let Son Vo make the first move. If he wanted a relationship, he could e-mail me through Ancestry.com.

A few weeks went by. I heard nothing. But there wasn’t a day that passed that I didn’t wonder about the son I never knew.

Then in May, I got an e-mail. Son wrote that he was surprised “about our DNA match and my high likelihood of being your child (son) from Vietnam…I just want to say hello and welcome you to contact me anytime you please. Or not. I’m not looking for anything. I do think it would be very interesting to communicate.”

I responded immediately, my fingers flying across the keyboard. “I wasn’t sure you’d want to hear from me. I am just as surprised as you are but eager to find out more about you.” I told him a little bit about myself and what I’d done in the years since Vietnam, then signed off: “I truly hope that you’ve had a good life.”

We e-mailed back and forth. Son told me his mother had married an American in 1973 and they’d emigrated from Vietnam when he was four—just two weeks before the fall of Saigon. Three years later, his mom had died of a brain tumor. Son went into the foster care system. He said he’d yearned to find me his whole life but didn’t have enough information. About a year before, he’d finally given up the search. His wife, Julie, had bought him the DNA kit. He never dreamed he’d actually stumble upon me.

After a couple weeks of e-mailing, I suggested a phone call. We both were extremely nervous, so there were a lot of awkward silences. Then Son mentioned that he played the bass. I told him that I used to play the bass too and that my dad had always wanted to be a country singer. From there, the conversation flowed.

I invited Son and his wife to come to Huntsville for Fourth of July weekend. That Friday, July 1, 2016, Debbie and I sat in the car, waiting in the arrivals lane at the airport for Son and Julie. What if we don’t hit it off in person? I wiped my sweaty palms on my pants.

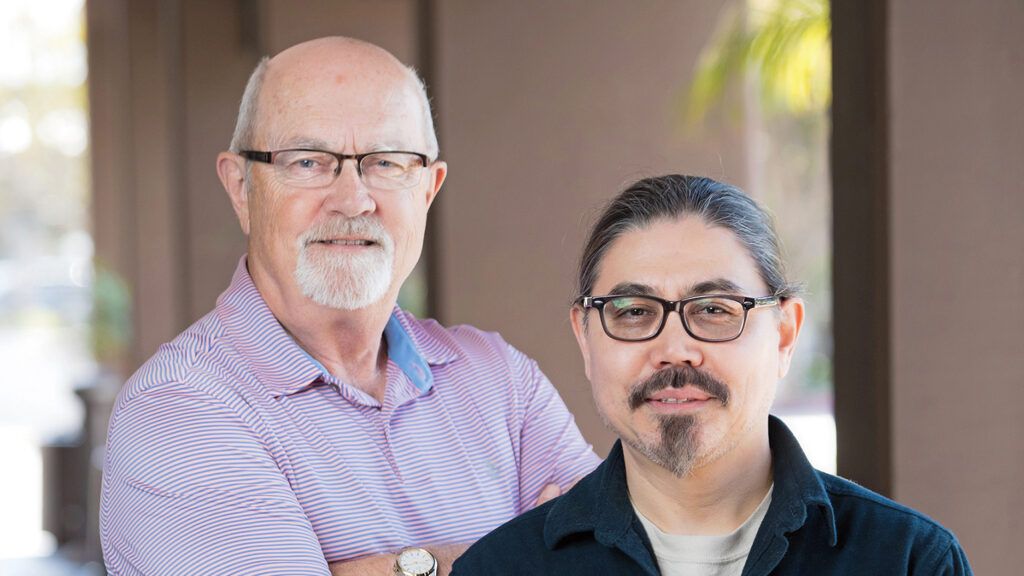

I recognized Son right away from his photos on Facebook and from the guitar slung across his back. The moment I saw him, I was flooded with joy.

I got out of the car. Though I’m normally a pretty reserved guy, I opened my arms wide, and we hugged right there on the sidewalk.

“I’m so sorry I wasn’t there for you when you were growing up,” I said. “I missed out on having a son, and you missed out on having a dad.”

“I understand,” Son said, looking me right in the eye. “There wasn’t anything you could have done about it.”

I took Son to meet his half-siblings—Mandy, James, Audrey and Justin—and their families. With his easygoing nature and great sense of humor, Son hit it off with everyone.

“Oh my goodness, your noses look like they’ve been cloned,” Audrey exclaimed, looking at Son and me.

“And you both have the same cadence to your speech,” Mandy said.

A little later, Son pulled out his guitar for an impromptu jam session. I marveled at his confidence and talent. I’d always wished that my kids shared my love of music. I was so glad that here I had one who did. We even sang harmonies together, and Son said he could hear his own voice in mine.

All these years, I’d thought of my service in Vietnam as a dark period, a negative experience. But sitting next to my newfound son and hearing my voice join with his, I was finally able to lay those feelings to rest. Something good had come out of my time in Vietnam, something amazing.

“This is nothing short of a miracle” is how Son puts it. Even though I’m not particularly religious, I have to agree. Getting to know and love my oldest child, my son Son Vo, is an unexpected blessing God has bestowed upon me, for which I am eternally grateful.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.