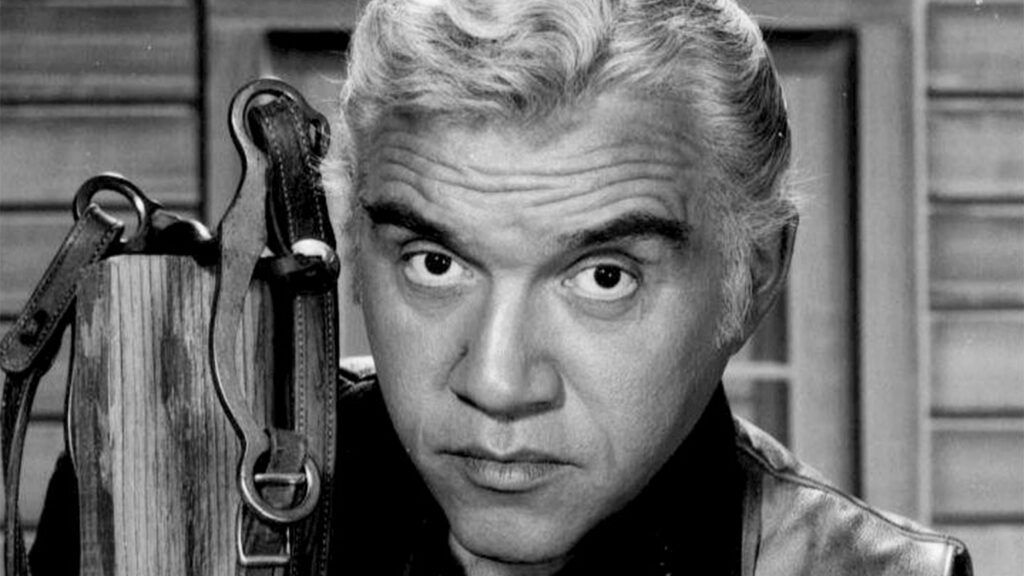

In 1956, three years before I was given the part of the father in Bonanza, my father died. But in another sense he lives every time Ben Cartwright walks before the TV cameras.

The way the role was originally conceived, for example, Cartwright was an aloof, unfriendly sort of person who greeted strangers with a rifle. I remember one early line I had to speak.

“We don’t care for strangers around here, Mister. Git off the Ponderosa—and don’t come back!”

Well, I said it, but my heart wasn’t in it, and gradually I began to play Ben Cartwright more like the father I knew best.

His way of greeting strangers was to invite them home to dinner. There were only three of us in our family, Dad, Mother and me, but our house in Ottawa, Canada, always seemed to be full of people.

My most typical childhood memory is of creeping halfway down the stairs after my bedtime to listen m the company talking in the living room—and wondering in the morning who had found me asleep there and carried me back to bed.

The people Dad, who made his living as a shoemaker, invited home most often were actors, artists, musicians, anyone connected with the world of beauty and make-believe that had been closed to him as a child and young man.

Dad’s family had been poor. He’d gone to work early, apprenticed to a leather worker at 15, and Dad’s friends filled in a part of life he’d missed.

Dad was a huge man. He wasn’t unusually tall, but he was tremendously broad across the chest and shoulders. And like so many big men, he was exceptionally gentle.

He had one special quality which I have come to think of as the essence of his fatherhood. It’s such a simple thing, on the surface. He knew that there is a time for silence.

I remember the day I discovered this quality in my father. It was my eighth birthday, and Mother and Dad had given me a watch—a gift so far beyond my wildest dream that I had to keep taking it from my pocket to be sure it was real. At bedtime Dad warned me about winding it.

“It’s wound tight now. Tomorrow, when it’s run down some, I’ll show you exactly how to do it.”

Of course, I promised not to wind the watch and went to sleep in a fever of impatience for the morning.

Several times that night I woke up: would daylight never come? At last I drew the watch from safekeeping under my pillow, stared into its phosphorescent face and came to the incredulous conclusion that it was not yet three o’clock.

Surely it was later than that! My watch must be losing time! It was as though my dearest friend lay dying in my arms. Dad had said not to wind it, but wasn’t it almost murder to let it run down?

And so after a regrettably brief struggle, I wound the watch. After every few twists I held it to my ear but the watch ran no faster. Desperate now, I wound and wound until finally, I fell asleep…

Early next morning Dad came into my room. “Well Lorne! What time is it?” Dad picked up the watch, his eyes still shining with the pleasure that giving the gift had brought him. Then he frowned. “Five minutes past three?” he said. He held it to his ear, then tried the stem. “Lorne, did you wind this watch?”

I must have felt much like Adam in the garden, with the taste of apple still in his mouth. “No, Dad, I didn’t wind it.”

I looked up at Dad and there in his eves I saw some deep communion broken. For a full 10 seconds he watched me without speaking and then he left the room.

He didn’t speak of the matter, then or ever, and he had the broken mainspring on the watch repaired, but his silence demolished me. I sobbed for hours. I hated myself—whereas a lecture might have let me twist things around and hate him—and I never forgot it.

I was 15 before I tried deception on my father again—and this time I went in for it in a big way. It happened that Mother went to New York for two weeks to visit her sister, leaving Dad and me alone in the house.

The more I thought about that house, standing empty and peaceful all through the day while Dad was at the shoeshop, the more delightfully it contrasted with the restraints of school.

I took out a sheet of Mother’s note paper, experimented with her signature until I was satisfied, then signed an illness excuse and began to enjoy a few days of leisure.

One morning I picked up my pile of hooks as usual, and left the house. Dad always left for his shop at 8:30, but I was taking no chances: I waited until 9:30 before going home. I let myself in, gloating at my own cleverness, and slammed the front door behind me.

“Who’s there?” Dad’s deep voice boomed through the hall.

He stepped out of the bathroom, a towel around his shoulders, and my cleverness deserted me. Staring into his eves the only thing I could think of was:

“I—uh—came back for an umbrella.”

Both of us instinctively glanced out the window. As luck would have it there was not a cloud in the sky. In the immense silence proceeding from my father I went through the wretched pantomime of taking an umbrella from the closet. I was halfway out the door when he spoke.

“Aren’t you forgetting your rubbers?”

Miserably, I crept back for those, too.

“Lorne,” Dad said, “let’s you and me have lunch together today.”

Now ordinarily this was a great treat, to meet him at a restaurant downtown during the school lunch hour, and I tried to sound hearty as I accepted.

I knew what that lunch date was for: it was a chance for me to tell him anything that might be on my mind. But somehow when I got there the words stuck in my throat.

Dad didn’t press me on the subject of my behavior; he maintained that prayerful silence of his which said so much more than words. After the meal, he said simply, “I’ll walk you back to school.”

We walked up the high school steps, down the hall, into the principal’s office, and there, of course, it all came out: the illegal absences, the forged note, everything.

That principal bawled me out for half an hour. He threatened and harangued and banged the desk and said a great many things, all of which were probably very well put and doubtlessly true. And five minutes after we left his office I couldn’t have told you one of them.

All the while Dad said nothing at all. He simply sat looking at me. And whereas I cannot tell you a thing the one man said, the well-timed silence of the other has haunted me ever since.

I remember once during my first semester at college when I faced a decision about the future. I was enrolled in the chemical engineering course at Queen’s University in Kingston, Ontario, about 100 miles from home.

I’d been intrigued by chemistry for years, but I had another love, too, perhaps born on the hall stairs one night as Dad’s guests talked in the living room. I wanted to be an actor. Not professionally, perhaps, but as a hobby. One reason I’d chosen Queen’s University was because of the Drama Guild there.

But as soon as I started classes I made a jolting discovery: being a scientist was going to take all of my time! There were lectures in the morning, labs all afternoon, and written assignments for the evening. Only people in non-lab courses could go out for the Drama Guild.

Suddenly I wanted very much to be talking this all over with Dad. I put through a phone call and raced the three-minute limit to get it all said.

“Isn’t this a coincidence!” Dad’s voice interrupted me. “I’ll be passing right through Kingston tomorrow on my way to Toronto. Why don’t I stop by the school and you can tell me more?”

Today, of course, I know he didn’t have to go to Toronto any more than he had to go to the moon. He closed his shop and made that 100-mile trip because there was a boy with something on his mind who needed a good listener.

At the time I only knew that we sat all that September afternoon on the shore of Lake Ontario while I poured out my thoughts, my hopes, my dreams for the future, and that by the time I had finished I had chosen a lifetime in the theater.

What he thought about my plans, whether he would have been prouder of an engineer in the family than an actor, or whether he cherished completely different dreams for me, I never knew.

I was talking with a friend not long ago about Dad’s gift of creative silence. My friend, Joe Reisman, is a song writer, and suddenly he picked up a piece of paper and started jotting down some of the things I’d said. Here’s what he wrote:

You can talk to the man.

He’s got time. He’ll understand.

He’s got shoulders big enough to cry on.

Tell all your troubles, and take your time.

He’s in no hurry. He doesn’t mind.

It matters not how bad you’ve been:

You can talk to the man.

Now I’d been talking about Dad. But by the time Joe had set the words to music and we’d made a record of them, the word “Man” had become capitalized, arid the record was about God the Father of us all.

But that’s a natural progression, when you come to think about it. Doesn’t what we know of the Father in heaven start with a father here on earth? We believe in His love because we’ve known human love. We believe that He listens to our prayers because another father has listened to our words.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.