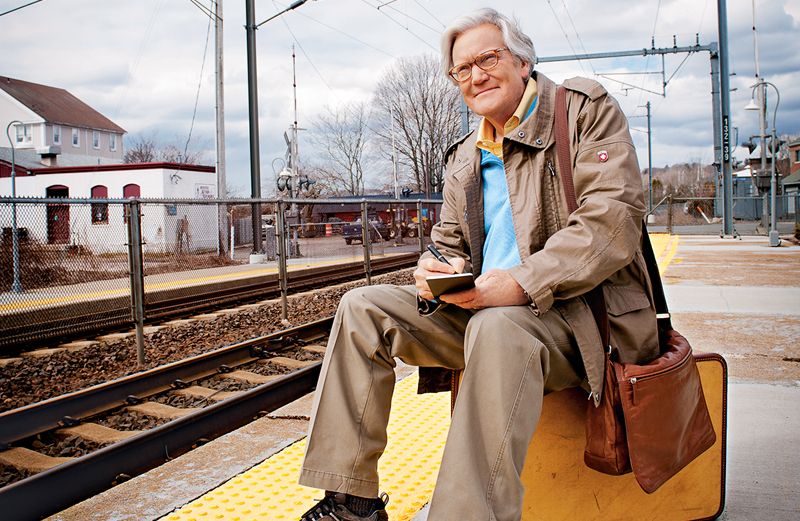

On my NBC Today show segment, “The American Story With Bob Dotson,” I’ve talked with countless ordinary Americans whose ingenuity and pluck express the best of our country, people whom most TV journalists wouldn’t notice. A New Yorker who paid for his three granddaughters’ college educations by selling potato peelers on the street. Or kids in a remote Alaskan village who formed a lifesaving ambulance brigade.

It seems everywhere I travel I find remarkable people in unremarkable places. In fact, I’ve come to believe everyone is remarkable. If our leaders—and our television reporters—would take more time to listen to the wisdom of ordinary, resourceful Americans, our country could solve many of its most intractable problems.

You might ask why it’s so hard to get powerful people to slow down and pay attention to ordinary folks. I’ve got a slightly different question. What made me slow down and listen?

After all, when I was getting started in the news business, I was just as hungry as the next young reporter for conventional success—a network reporting job, or maybe one day anchoring a national newscast. What put me on a different path?

The answer is one story I’ve never told on television. It starts the day I graduated from the University of Kansas, back in 1968. I was sitting in a café in Lawrence with my dad, having a cup of coffee.

Like most times we were together, we weren’t saying much. We didn’t dislike each other. But we didn’t really connect, either. Dad always wished I’d been more athletic, less bookish. We rarely talked about anything in depth. By that point in my life I felt like I hardly knew my father.

Suddenly Dad put down his coffee cup and fixed me with a strange look. “You know,” he said, “I never graduated from college.”

I put down my own cup. “Excuse me?” I said.

“That’s right,” said Dad. “I never graduated from college. I never did what you just did.”

For a moment I didn’t know what to say. My dad was one of the most successful, hardworking people I knew. In fact, that’s part of the reason we didn’t have much of a relationship.

Dad owned an optical store near our home in St. Louis. He knew all about optometry. He’d fitted thousands of people with glasses. He worked constantly, and when he came home he buried himself behind a newspaper. Didn’t you have to go to college to fit people with glasses?

“What do you mean?” I asked.

Dad’s face filled with emotion. “I dropped out of school in fifth grade,” he said. “I had to. My dad skipped out on our family, joined the Army and never came back. I had to go to work to help my mother feed us—me and my younger brother and sister.”

I was stunned. I’d never heard my dad talk like this before. I’d been a pretty self-involved teenager. I’d just assumed my dad was like all the other plain-faced, plainspoken working dads in our neighborhood. A real square.

Dad’s expression tightened. “Eventually Mom couldn’t take care of three kids. She sent me to work for a farmer. I was just ten years old. When I was eleven I went to St. Louis and worked as a janitor in a car factory sweeping the floors.

"All the workers on the assembly line where I cleaned were immigrants. They didn’t speak English. It was pretty lonely.”

Dad said he eventually became a janitor at a St. Louis optical store. With the owner’s encouragement he went to night school. “I took classes for twenty-three years!” he exclaimed with pride.

He received an honorary master’s degree in ophthalmics. He bought a lens grinder and opened Dotson Optical Company. The business paid for our house, the food we ate, the clothes we wore—and my college education.

Dad fell silent after his story. We didn’t say much more about it. It was like a weight he’d carried with him all those years. Now he’d handed that weight to someone else.

For a while I wasn’t sure what to do with this revelation. But as I made my way through a few odd jobs before landing at the NBC station in Oklahoma City, I kept remembering Dad’s face—his shame, followed by the flash of pride at his accomplishments.

Behind his stoic exterior smoldered an extraordinary story. What other stories lurked like that in forgotten corners?

A couple of years later I was working on a piece about pioneering African-Americans in Oklahoma. So far I hadn’t come up with a lot. Even the librarian at a university built for black students in the state said they didn’t have much material.

Working with an African- American cameraman from the station, I crisscrossed the state looking for people who remembered the early days. But I needed historical footage. One day I crawled into a tiny storage area at the station wedged between the dropped ceiling and the roof of the newsroom.

I pawed through stacks of archived film. Suddenly a box caught my eye. Pathé, it said on the side in old-fashioned lettering. That was the name of an old newsreel company. I opened the box. Stacked inside were reels and reels of news footage from the 1920s and 1930s.

A name was written on the reels: Bennie Kent. He’d been a Pathé cameraman long ago. Most of his footage would have been sent away to New York to be edited into newsreels for national distribution. This was the stuff he’d deemed of no interest to editors. For some reason he’d saved it.

I found an old projector and watched the footage. Flickering black-and-white images appeared of people walking the streets of old boomtowns. There were long sequences of Native Americans living lives untouched by Western ways.

Then, to my astonishment, came footage about entire towns populated and governed by African-Americans. They were freed slaves excluded from white communities who went out to found their own communities.

Immediately my cameraman and I raced out to find some of these people. We ended up speaking to several African-Americans in their nineties who remembered living in all-black towns. Our segment won awards. I got lots of kudos. But I cared less about that than about something deeper.

Every time I looked at that old footage or interviewed another nonagenarian startled to be asked about his or her long-ago past—all the work I did putting that story together—I had my dad in mind. I thought of the weight he’d carried all those years, of all his private struggles and hardships before he became a success in life.

The world is like that. We all carry the weight of our own stories, happy or sad. We are better when we share them. We’re better when we hear those stories and recognize ourselves.

I think that’s part of what God means when he instructs us to love our neighbors as ourselves. We are, in the end, each of us a collection of stories. We love each other by embracing those stories, honoring them and learning from them.

From the time I came across that old film I’ve steered a course different from most television reporters. While the journalism world speeds up on Twitter and aims for quick ratings hits, I’ve slowed down and trusted in viewers’ inherent goodness.

So far my trust has been rewarded. Every year I have to persuade my editors to keep my segment on the air. Every year “The American Story With Bob Dotson” ends up being one of the most watched and loved segments on Today. That’s not because of Bob Dotson. It’s because of the stories.

Like my dad taught me, it’s the story that holds life. Tell the stories, and the rest will take care of itself.

Download your FREE ebook, True Inspirational Stories: 9 Real Life Stories of Hope & Faith