It’s hard not to despair over climate change. A recent United Nations report revealed that human-fueled global warming is destroying habitats and species at an alarming rate, but many of us wonder how we can help beyond using the recycling bin. In 2011, John and Molly Chester decided a radical change was the only way for them to have an impact. They paused their careers, found investors and volunteers, and bought a farm an hour north of Los Angeles, trading traffic and show biz for manure and manual labor.

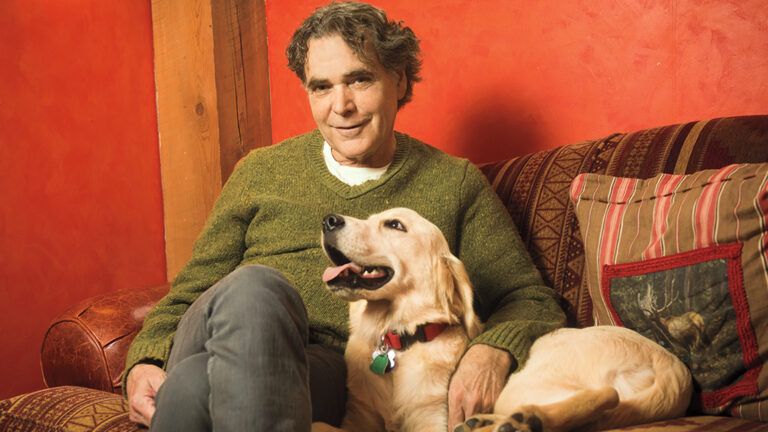

Their eight-year experience is unsparingly presented in the just-released film The Biggest Little Farm. We caught up with John to hear about how the pair turned 200 barren acres into a thriving regenerative farm that, despite pests, wildfires and hungry coyotes, is sustaining orchards, plants, animals and a simpler way of life.

Did you have farm experience or animals growing up?

I was around farm animals as a kid. In my late teens and into my twenties, I worked on corn and soy farms, repairing fences and mowing. I loved being around animals and felt a deep connection to nature. Molly grew up in the Pittsburgh suburbs, but her grandma had a farm, so she spent her childhood going there.

How do you feel those experiences affected you?

I definitely think they had a ripple effect. I saw how life could be simple, and that stayed with me. It made me more connected to something purposeful.

What were your original career paths?

We lived in L.A. for four years, and each of us got to the top of our games. I earned Emmy Awards for films and documentaries. I filmed everything from nature and wildlife for Animal Planet to short films for Oprah’s network to rock and roll documentaries. Molly was really busy as a private chef for celebrity clients, specializing in traditional food. Her spare time was spent sourcing locally, learning ancestral methods and researching how food was being grown.

Though your jobs gave you both a hand in the natural world, a big nudge toward your new life came from an unexpected source, right?

I was making a show that involved filming a hoarder and stumbled upon a beautiful black dog. I connected with him instantly and begged the owner to give him to me. Surprisingly, she did. I made the dog a promise that after everything he had been through, I would never give up on him. His name is Todd. Viewers will see in The Biggest Little Farm how Todd’s barking became a problem in our L.A. apartment. Although we tried everything, we eventually got evicted. Our commitment to not giving up on this dog drove us to a solution.

So you decided to move for Todd’s sake. What other needs ended up being fulfilled with this change?

There were other pressures. We had offers to do fun things, but they didn’t seem meaningful. We felt a disconnection from purpose. We realized that moving to a farm not only solved our Todd problem but also was the path that would reconnect us with purpose and living in a more environmentally conscious way. It made sense: Molly loved food; I loved farms and animals.

What was your first challenge when you bought Apricot Lane Farms?

We didn’t know how depleted the soil was. For 45 years prior, an extractive method was used to grow food cheaply. So it was not biologically diverse; there were no worms. We had a soil bank that was bankrupt.

But you found a guide, who is also such a fun character in your film.

Yes, we’re so grateful for Alan York, one of the world’s most respected soil, plant and biodynamic consultants, who advised us all the way through. Molly had such an optimistic view of his consulting; I was more skeptical. It’s easy to think this way of farming won’t work, but if you love the complexity of nature, then you have to believe in it. As Alan would say, “We’re trying to mimic a mutualistic biological diversity through the enhancement of biodiversity as a way to regulate the farm against epidemics of pests and disease.” That is, growing food of depth and density, the health of trees and crops, all depended on the health of that soil, and bringing it back to life. And all the tools of nature are there if you take the time to observe and innovate.

In the film, the challenges that you and Molly, the orchards and the animals faced seemed relentless. How was the process of discovering the solutions?

Innovation comes from boundaries we set for ourselves. When it’s hard and you feel lost, believe in your ideas. They can open doors, force some innovation. I think that’s a beautiful thing. This work is for someone who wants to be on their farm, walk it and observe it. Once I realized that was a big component, the complexity and diversity wasn’t scary.

It seems as if you’ve not only found purpose but also happiness in leaving city life.

Where there was nothing, we now have 75 varieties of orchard fruit, a garden, cows, sheep, chickens, ducks and a pig named Emma, who nearly died after giving birth. She is best buds with Greasy the rooster. Their friendship has made us see other special aspects of farm life. Greasy was the company Emma needed after her piglets grew up and moved on. And Emma was the protection Greasy needed from those hungry coyotes.

It’s all been eye-opening. It’s about more than just recreating a native habitat. It’s about rebuilding the soil that is the basis for all life. And, for us, doing that is as good as it gets.

Find out more at biggestlittlefarmmovie.com and apricotlanefarms.com.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to All Creatures magazine.