The hardest-working animal of all time? With all due respect to the honeybee, there’s really no contest. Scratch the surface of history and everywhere you find the sturdy little animal known variously as the burro, the ass or the donkey.

From the Old World to the New, from desert to mountain to jungle, the donkey is everywhere, doing just about everything.

The Sumerians—the world’s oldest city dwellers—used a species of wild donkey called the onager to haul their goods some 5,000 years ago. The ancient Egyptians wouldn’t have gotten far in building the Pyramids without the donkey’s help.

And Damascus, the world’s oldest continually populated city, was once known as the City of Asses because of the number of these animals that carried goods and people through its narrow streets.

From tractors to taxicabs, from grain grinders to water pumps, the work of the world that machines do for us today was, in times past, done in astonishingly large part by this patient, humble and absolutely essential animal—the quintessential beast of burden.

Considering everything it has done for human civilization, the donkey has received precious little thanks in return. When the donkey is mentioned at all by writers ancient and modern, mostly its character flaws come up. Stubbornness and noisiness top the list, but many have even called it lazy.

Not that all of these criticisms are completely off base. The donkey has indeed always liked to go at its own pace, and that pace always seems to have been a little slower than what its masters wanted.

It’s also true that the donkey doesn’t have the most melodious voice. Its ear-splitting bray inspired Gulliver’s Travels author Jonathan Swift to dub it the nightingale of brutes.

But for certain people—those with the eyes to look a little longer and a little deeper—the donkey has a special quality. One that has nothing to do with the work it does or how fast or slow it goes. A quality that might be described as soulfulness.

Certainly the Nobel Prize-winning Spanish poet Juan Ramon Jimenez knew as much. In Platero and I, his most beloved book, Jimenez describes Spanish village life through his relationship with Platero, “a small donkey, a soft, hairy donkey: so soft to the touch that he might be said to be made of cotton, with no bones.”

The English romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge also saw into the donkey’s sensitive soul:

Poor little foal of an oppressed race,

I love the languid patience of thy face;

And oft with gentle hand I give thee bread,

And clap thy ragged coat, and pat thy head.

Then there’s the revered French filmmaker Robert Bresson. In 1966 Bresson made Au Hasard Balthazar, a film that was both a deep expression of his Christian faith and what some critics claim is his masterpiece. The film’s tragic hero, Balthazar, is none other than a donkey, who finds both compassion and cruelty as he moves from master to master.

Any close reader of the Bible knows donkeys are important. With over 100 references, the donkey just might be the most conspicuous animal in the Bible. When Abraham is called to Mount Moriah to sacrifice Isaac, he travels on a donkey. Donkeys are part of the payment given by Pharaoh for Abraham’s wife when he takes her into his harem.

When wood was hauled from the forests of Lebanon to build the Temple at Jerusalem, donkeys did the heavy lifting. The donkey even features in the Tenth Commandment, which prohibits coveting thy neighbor’s wife, goods, ox or ass.

In the biblical story of Balaam’s ass, the donkey actually talks. Balaam was on his way to Moab to ridicule the Hebrews, Numbers tells us, when his donkey balked because she saw the angel of the Lord in her path.

“When the ass saw the angel of the Lord, she fell down under Balaam: and Balaam’s anger was kindled, and he smote the ass with a staff. And the Lord opened the mouth of the ass, and she said unto Balaam, ‘What have I done unto thee, that thou hast smitten me?'”

The angel of the Lord then appears before the astonished Balaam and chastens him, both for striking his donkey and for his blindness to God’s desires.

The donkey’s appearances in the Bible are not confined to the Old Testament. In fact, it’s precisely when the epic journeys, mighty battles and other grand doings of the Old Testament give way to the humbler happenings on the shores of the Sea of Galilee that the donkey really comes into its own.

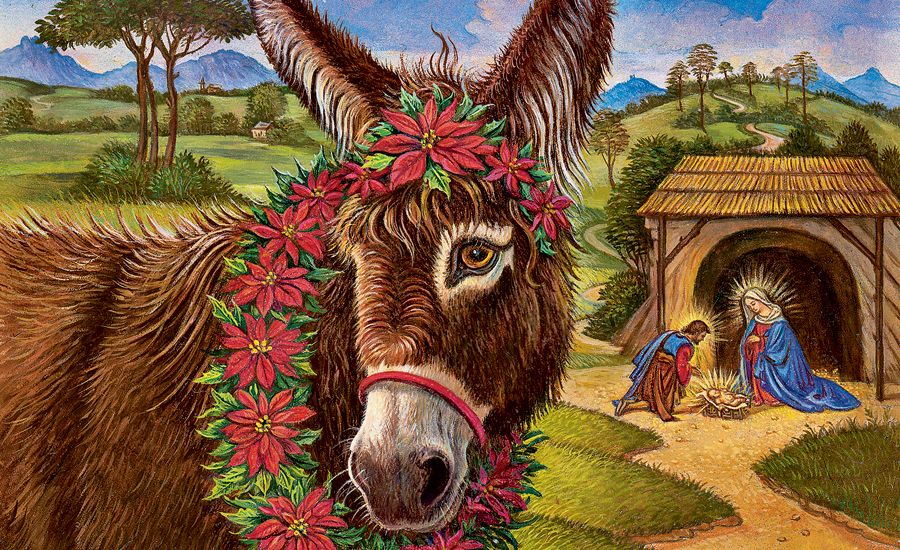

As the Christmas narratives make plain, no other animal was closer to Jesus. Joseph brought his pregnant wife to Bethlehem on a donkey. Likewise, when Jesus was born, a donkey—along with an ox and a sheep—was present in the stable. And when Mary and Joseph fled into Egypt with their newborn child, a donkey carried them there as well.

Donkey historian Frank Brookshier, in his book The Burro, makes the interesting point that “in his early years as a carpenter Jesus doubtless owned a burro for riding and transporting the tools of his trade.”

Perhaps that’s one reason why, when Jesus makes the single most important trip of his life, into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, he specifically chooses a donkey to ride on. The cross of dark brown fur that the donkey carries on its back is said by folk belief to be a mark of this event, the greatest of all its feats.

There are important historical reasons for Jesus’ choosing a donkey for that last and greatest journey. In doing so he was fulfilling a prophecy that the Messiah would come into Jerusalem, as Matthew puts it, “meek, and sitting upon an ass.”

But the basic message Jesus conveyed with this gesture shows that, history and prophecy aside, he knew what every donkey lover in history has known. In their comical, occasionally stubborn, but more often lovable way, these hardworking animals are an embodiment of the message that lies at the very heart of the Christian story.

True holiness is found not in temples and palaces, but in the humblest, poorest, most ordinary places—and in the people and the creatures that the world most often takes for granted.

Looked at from that perspective, it’s only fitting that the long-suffering donkey—the little animal that carries the world on its back—should have ended up carrying the person who himself came to carry, and redeem, the world’s burdens once and for all.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Angels on Earth magazine.