The patient was in his 40s, but he shuffled into my office like a man twice his age. He gripped the back of a chair and lowered himself into it, wincing. “I don’t know what to do,” he said. “I’m still hurting. I keep praying about it. But the pain won’t go away.”

I looked at the man’s chart. His name was Robert. He had fallen at work, then undergone a difficult back surgery. He had already been to see me several times.

As I do with all my psychiatric patients, I had taken a detailed psychological and medical history. I had even asked about his faith—he was a deacon at his church.

Many patients tell me faith is an irreplaceable source of consolation. But that day, Robert confessed to a very different kind of anguish.

“I’m going to tell it to you straight, Doctor,” he said. “I’ve been praying hard about this pain. Every day and night. But it’s been years, and it’s just as bad as ever. Dr. Koenig, I want to believe that God can heal me. But I think I’m losing my faith. I don’t know why God would do this to me. Can you help?”

I put down my chart and looked at Robert, overcome with compassion. Yes, I thought, I can help you. I know exactly how you feel.

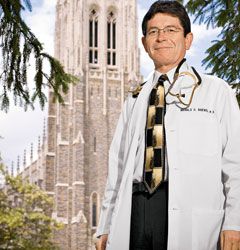

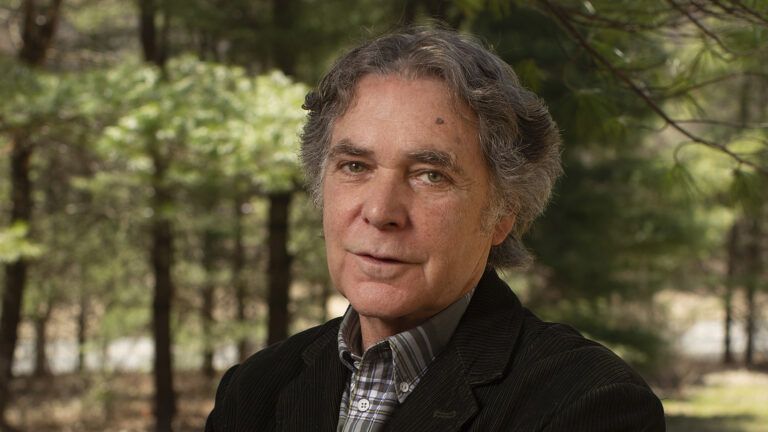

Years before, I had been an ambitious young doctor at Duke University. I was in my early 30s and newly married. I had climbed mountains—Mount Kilimanjaro, 14,000-foot peaks in the Rockies. I swam a mile a day and lifted weights. My wife Charmin and I planned to have a baby.

I was strong in my faith too—I felt a powerful calling to bring the love of God to the sick, especially to older patients, who are often shunted aside. I saw lots of patients, applied for research grants and began a wide-ranging study of depression. I felt like an energetic vessel for God’s healing work.

Then, one day, I noticed that my right knee and ankle were sore at the end of a hectic day at the hospital. I shrugged off the pain, chalking it up to an old high school wrestling injury. But the pain persisted, then spread to my right wrist.

After a day writing notes and prescriptions, my hand was unnaturally sore. God, I prayed, you called me to this work. Surely you will keep me healthy enough to do it.

One morning, I went to the garage to change the oil in our car. Lying under the engine, I reached to pull the old filter out. The filter stuck, and my right hand slipped and smacked against a bolt. Pain lanced through my knuckle, then settled into a dull reverberation.

I tried tugging at the filter again, but discovered I could barely move my hand. I slid out and sat up and looked at myself. My knuckle was swollen, and it stung and ached when I touched it.

I’m sure it will go away, I thought. But it didn’t. At church, I could barely shake hands with friends. God, please take care of this, I asked. But at the hospital, I had trouble even holding a pen.

Clutching a stack of blank prescription orders, I paced the halls, too embarrassed to ask someone to fill them out for me. Finally, I tried a typewriter. To my relief, I found I could tap the keys with my left hand.

I brought a typewriter from home and lugged it under my arm on my rounds. I looked ridiculous. But what else could I do?

A week later, my finger was still swollen. And my ankle had flared up again. I was limping from room to room. I decided to see a specialist.

When I returned from the doctor, Charmin was playing with our baby boy, Jordan. “Well?” she asked. “Is everything all right?”

“I’m afraid not,” I told her. I had been diagnosed with psoriatic inflammatory arthritis.

My immune system was attacking my tendons and joints. Any part of my body I used repetitively—legs, knees, ankles, hands, shoulders, back—could become inflamed. The disease could be progressive. There was no cure.

Part of me was relieved to have a diagnosis—no more mystery pain. But then I saw the fear in Charmin’s eyes. I knew she was already mourning our walks together, our hiking vacations. I looked at Jordan. What kind of father will I be? Will we play baseball together? Can we even roughhouse?

That night, I lay in bed, unable to sleep. My back was throbbing. But it wasn’t just the pain keeping me awake.

Why? I asked, cycling through thoughts of patients, research, all that I felt God had called me to do. Is all this work for nothing? Is it all going to get swallowed up in some disease? What am I supposed to do?

The bedroom was dark, the pain relentless. Finally, I got up and limped to the sofa in the living room. I lay on it and found the soft cushions eased the ache. Thank you, God, I prayed.

And then it hit me. It was such a simple movement, from bed to sofa. God didn’t snap his fingers and make the pain go away. He didn’t promise to cure me. But he did show me how to adapt, how to live instead of giving up.

Maybe that’s what I’m supposed to do, learn to follow God with the pain—and then help others do the same. Lord, that sounds hard. But if you’re with me, I’ll try.

And so there I was, sitting across from Robert, scribbling notes with my left hand, which doesn’t hurt as much, so I learned to write with it.

As I looked at Robert slumped before me, all but defeated, I thought of my other adaptations. The wheelchair I use to scoot through airports on my way to speaking engagements. The voice-activated computer that takes down dictated papers.

“Robert, I’m sure we can find a way for you to live with your pain, adapt to it instead of letting it take over.”

Robert’s eyes brightened, then faded. “That’d be wonderful. But how do I know if it will work? What if I’m stuck with this pain forever?”

“You’re right,” I said, reaching out and resting my hand on Robert’s shoulder. “There are no guarantees. But let me tell you what I’ve discovered from years treating patients. Sometimes God heals our bodies; sometimes he doesn’t.

“In my case, he didn’t heal my body. But he gave me another kind of healing. He showed me how to live with pain and how to help others. That’s drawn me closer to him than a healthy body ever could. I know he can do the same for you.”

We bowed our heads. When our prayer ended, the office was silent. Then Robert looked up at me. “Thank you,” he said.

No, I thought, thank you. For reminding me, as all my patients do, that God works through our weakness as well as our strength. As Robert headed out the door, I realized I had learned that lesson only through my own illness, my own years of pain and adaptation.

I had some time before my next patient, so I sat and reflected. Then I bowed my head and said a simple prayer of my own. Thank you.