Did you know that truck driving is one of the unhealthiest professions in America? Obesity, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, smoking, limited physical activity, fewer than six hours of sleep per day… In a national survey, 61 percent of long-haul truck drivers have two or more of these health issues. I know what that’s like because for nearly four years, I was a truck driver myself, for Prime Inc., one of the largest trucking companies in the country.

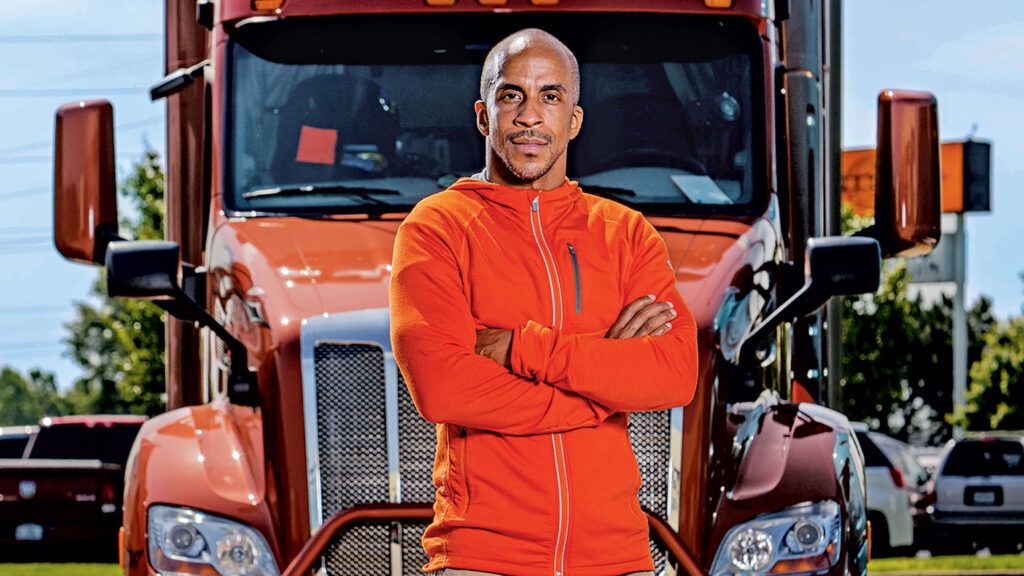

Now I do something different: I’m the driver health and fitness coach for Prime. I also founded my own company, Fitness Trucking, designing health and fitness programs specifically for the truck driver lifestyle. An unusual occupation, especially for a Yale grad with a philosophy degree. So how did I end up here? I’m kind of surprised myself.

Then again, I’ve never done what was expected.

Not even when I was a kid growing up in Oswego, Illinois. Back then, my name was Tony Blake. My family was the first African-American family in the neighborhood. I always stood out. My dad took what could’ve been a negative situation and encouraged me to turn it into a positive. Being different was my motivation to be the best at everything, from academics to athletics. When Dad saw my competitive fire, he introduced me to a distant cousin, Hayes Jones, who’d won the 110-meter hurdles at the 1964 Olympics.

Hayes let me hold his gold medal, and I thought, I want to win one too. I was good at football and basketball, but I’d never have the size to go far in those sports. I turned my focus to swimming. So what if there had never been an African-American swimmer in the Olympics? I’d be the first! At age 10, I won my first state championship. I kept winning. By the end of high school, I’d grown to 5’8″, 140 pounds. Though usually the smallest guy in the pool, I made up for it with intensity and technique.

I was accepted at every college I applied to, including five Ivy League schools, Stanford and the University of Virginia. I was also offered full scholarships at a few other universities. I opted for Yale. No one could understand why I’d chosen a college that doesn’t even give out athletic scholarships. Not only that, the swim team had the worst record in the Ivy League, 5-7.

Like I said, I never do what’s expected. But I had my reasons. At Yale, I’d be a big fish in a little pond. I could lift the team from the bottom of the barrel to the top of the Ivy League. Each year I swam for Yale, our team got better. My junior year, we had a 9-1 record. I entered the U.S. Open Swimming Championships, my best chance of qualifying for the 1992 U.S. Olympic team trials. I needed to have the meet of my life. But in my best event, the 100-meter freestyle, I missed qualifying by eight tenths of a second.

My Olympic dream died in eight tenths of a second. A part of me died too. Senior year, I just had no desire to swim anymore. The coach talked me into staying on to help our team win the Ivy League championship. At our meet against Harvard and Princeton, I swam the lead leg of the 4×100 relay and got us a big lead. We ended up winning the relay and, with it, a share of the Ivy championship. It was the culmination of my swimming career.

Three days later, I left Yale, a few months short of graduation. No one understood, not even my dad. “All you’ve got to do is take your exams, Tony, and you’ll have your degree,” he said.

I wasn’t going back. I’d read about Jesus, Buddha, other spiritual luminaries. Now I needed to explore the world, to find out who I was meant to be.

For the next 15 years, I was a nomad, traveling Europe, the Caribbean, Africa, working odd jobs. I came back to the U.S. briefly in the late 1990s—I finished up my degree at Yale, then worked at a few nonprofits. But I took off again, going to Africa to learn more about my ancestral heritage.

I went to Togo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Benin and South Africa, where I had the privilege of meeting with tribal elders. They told me that when a son of the soil returns, he is given a new name. For my first name, they chose Siphiwe, meaning “gift of the Creator.” For my surname, Baleka, or “he who has escaped.”

By 2008, I was in my mid-thirties and tired of scraping by. I couldn’t imagine myself in a nine-to-five office job. A friend who was a truck driver suggested I try his line of work. I liked the nomadic lifestyle. I’d get to explore America. I’d make good money. I didn’t have many living expenses, and I worked out a plan where I’d drive for three years, build some savings, then move on.

I signed up with Prime Inc., which is based in Springfield, Missouri. I got my commercial driver’s license, then went on the road, training with an experienced driver. After two months, I had a break and went to go visit my dad.

He gave me the once-over.

“What?” I asked.

Dad smiled. “I told you what would happen once you stopped swimming—do you remember?”

I remembered. He’d joked that I would get fat. I hadn’t been getting much exercise behind the wheel of the rig, but my body couldn’t have gone soft that quickly, could it?

I checked out my reflection in his bathroom mirror. My face was fuller. I lifted my shirt. For the first time in my life, I couldn’t see my abs. I got on a scale. I couldn’t believe it: 155 pounds!

I’d weighed 140 pounds all my adult life, and in just two months of driving, I’d gained 15 pounds. That doesn’t sound like a lot, but I’ve always been body conscious. When you’re a swimmer, you spend most of your time in skimpy swim briefs, so you’ve got to look good.

At this rate, I’d be 50 pounds overweight by the end of the year. I wouldn’t look good, and I definitely wouldn’t be feeling good. In trucking, it’s all about the delivery schedule. Every second counts. Eat. Sleep. Drive. That’s all you have time for. How was I going to fit in working out?

That night, as providence would have it, I was flipping through the channels on TV and came across an infomercial for the Range of Motion exercise machine. It was like a spin bike, rower and stair stepper all in one. The inventor claimed that four minutes on the machine would give the benefits of an hour-long workout. That’s ridiculous, I thought.

There was only one way to find out. I’d have to try it. Not the machine itself—it was massive and cost $15,000. But I came up with a workout replicating its movements, using my body weight as resistance.

Anytime I had a few minutes, I worked out. Burpees, mountain climbers, jump-tucks. Beside my truck at rest stops, I’d do each exercise at high intensity for 20 to 60 seconds, rest for 10 seconds, then repeat. “Get it in where you can fit it in,” I told myself.

Drivers wait in line at the receiving office for 20 to 30 minutes. I used that time to do squats and shadow-box. Some of the guys laughed at me. I became a running joke over the CB. It didn’t bother me. I don’t do what’s expected, remember? Besides, I was used to standing out.

But some drivers would come up to me and say, “Man, I really need to be doing this. Can you show me?” I demonstrated and gave them exercise and nutrition tips while exercising in front of my truck. The more I coached them, the more I realized my new routine wasn’t just for me. It was meant to help other people find their way to health. There was a real need and a real business opportunity here.

I drew up a proposal to become the in-house health and fitness coach and presented it to Robert Low, founder and president of Prime Inc. He was all for it. I studied corporate wellness programs and developed a 13-week program for our fleet. Interested drivers had to fill out an application and come in for a day of orientation.

Emily was one of the first to enroll. “I went to an amusement park with my granddaughter, and they kicked me off the ride because I was too big to buckle the lap belt,” she said. “I’m ready to make a change.” The average weight loss in that first group was more than 19 pounds. In the second group, I had a guy who lost 60 pounds in 13 weeks.

Their success inspired others to sign up. Drivers use an app to log everything they eat and drink. Once a week, we analyze their food logs and identify what’s doing the most damage to their metabolism and show them how to fix it. Improving nutrition and fitness isn’t complicated. What’s harder than changing your behavior is changing your thinking.

I’ll have people confess they’re embarrassed to exercise in front of others. “I’m 270 pounds. What if folks see me doing burpees and make fun of me?”

“What if they see you and think, Hey, if he can do it, maybe I can too?” I say to them. “Why not set a healthy example and be a light, like Scripture asks of all of us?”

That’s what I’ve found myself doing. For once, I’m doing what’s expected of me—in a totally unexpected way. And I’ve never felt more fulfilled.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.