Let me tell you about an African woman named Leonida Wanyama. For Christmas dinner her family had boiled bananas. That’s all there was. In the hills of western Kenya, Christmas comes during the dry season when fall harvests are often already depleted.

Farm families live on tiny portions of corn, tea, bananas, sweet potatoes, beans and a few vegetables. Babies cry with hunger. Children’s eyes dull with exhaustion. It happens every year. Here, as in so many parts of Africa, farmers, the women and men who grow the food, go hungry.

Except that this year Leonida Wanyama vowed that things would be different. A neighboring farmer had told her that an American organization called One Acre Fund was looking for farmers willing to try something new.

If the farmers agreed, One Acre Fund would supply them with hardy seeds, a bit of fertilizer, credit to pay for it and classes teaching modern farming methods. “They promise you will grow more than you have ever grown,” the farmer told Leonida.

Leonida is a woman of faith. She leads the choir at her village church. She prayed about the farmer’s offer Feeding Africa and studied her Bible. She came to this passage in Exodus: “I have promised to bring you up out of your misery in Egypt into a land flowing with milk and honey.”

Was this offer from One Acre Fund God’s deliverance from a lifetime of hunger? Leonida didn’t know. She decided to trust anyway.

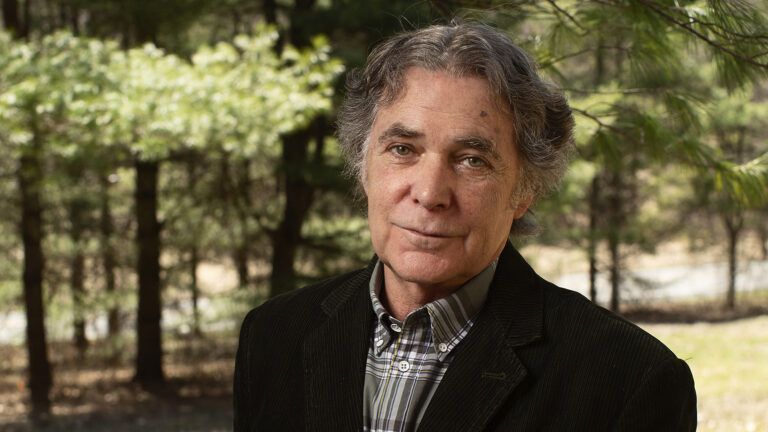

I met Leonida for a very simple reason. My life, too, was changed by a verse from Scripture. Though in my case the verse was from Matthew: “For I was hungry and you gave me food.” Those words gripped me the moment I read them. I’m not sure why.

I grew up in a place vastly different from Lutacho, Kenya. I was raised in Crystal Lake, Illinois, outside Chicago—the heartland, where modern farming methods have produced harvests that are the envy of the world.

Teachers at my Lutheran grade school made us memorize Bible verses. That verse from Matthew planted itself in my heart like a seed.

For a long time the seed lay dormant. I became a journalist, traveling the world covering stories. In 2003 I landed in Ethiopia to report on a famine for The Wall Street Journal. I walked into an emergency medical tent filled with severely malnourished children. A farmer was there with his five-year-old son.

Just one year earlier the farmer had carried surplus sacks of grain to sell at market. Now he carried his starving son to this feeding tent. His son weighed 27 pounds. I stared into the boy’s eyes. Emptiness stared back at me. For I was hungry….

I left that tent struggling to understand how such misery could exist in the twenty-first century, in a world bursting with food. How could a farmer, a person who brought food out of the ground…be hungry?

I tried to answer these questions by writing newspapers stories and a book about hunger. Poor African farmers, I learned, struggle to grow enough because they don’t have access to the high-quality seeds and fertilizers that have revolutionized farming in developed countries.

Global agribusinesses considered them too poor, too remote, too insignificant. Their own governments and international development agencies similarly neglected them.

Things never change because when harvests are bad aid agencies rush to ship food from America and Europe instead of helping Africans raise their own crops.

Right now almost one billion people around the world are chronically hungry. Unless global agricultural production nearly doubles by 2050 to meet the demands of an increasing population, there will be shortages and rising prices and perhaps even riots and wars over food.

The simple reality that people are not getting enough food could destabilize the entire world.

I learned a lot. But the deeper I dug, the more dissatisfied I grew. Global food problems can seem overwhelming. Yet Jesus’ words are so simple: For I was hungry and you gave me food. Where was God in this problem? I wondered. Where was the solution?

One day, in the middle of a Chicago snowstorm, I sat down for tea with a young man named Andrew Youn. Andrew was the founder of a tiny nonprofit organization called One Acre Fund. I was curious about his work; he wanted to learn more about a book I’d written on global food problems.

Andrew told me about a searing experience he’d had while in business school. He was in Africa doing research. He met a struggling Kenyan farming family enduring the hunger season. He watched a teenage girl stretch a bowl of thin corn porridge into a day’s worth of meals for her entire family.

It was an image, he told me, that lodged in his mind. Right away I knew that I had found a kindred soul.

Andrew invited me to go to Kenya to learn more about One Acre Fund’s work. Soon I met Leonida Wanyama and other small farmers bravely risking their livelihoods on One Acre Fund’s promise to help them grow more food.

I had met countless African farmers while reporting stories. Something about this trip was different. Maybe it was because one of my first stops was not at a farm but at Leonida’s church in Lutacho.

It was there that a One Acre Fund teacher—himself a farmer—was showing a sanctuary full of farmers how to plant seeds in rows and space the seeds out by measuring with knots tied on a string. Traditional African farmers scatter their seeds and tend them haphazardly.

The class felt like a church service. The farmers sang, prayed, clapped and shouted hosannas.

For the first time since I’d started writing about hunger, I felt a stirring of hope, a deep pulse of optimism, as if God was showing me answers to all of my troubling questions.

I decided to chronicle a year in the life of these farmers in Lutacho and the nearby village of Kabuchai, writing about their yearning to change their lives. The farmers had far to go.

Leonida was 43 years old. Hardly had a year gone by without her enduring Wanjala, what Kenyans call the hunger season when food runs out. She and her husband, Peter, lived on about two acres, and grew corn, a Kenyan staple, on half an acre.

They had seven children. Anything extra they earned went to school fees.

Another farmer I met, Zipporah Biketi, lived in a hut in Kabuchai with a thatched roof that leaked into the bedroom. Her two youngest children were given middle names for the season in which they were born, Wanjala. Literally their names meant Hunger.

And yet these farmers were faithful. When Francis Wanjala Mamati, a 53-year-old farmer also from Kabuchai, waited for his year’s distribution of One Acre Fund seeds, he bowed his head and prayed silently. The entire gathering of farmers prayed, too, for rain and a plentiful harvest.

“Amen,” Francis whispered when the prayer concluded. “Amen.”

The year did not begin well. The farmers got their seeds and fertilizer on time—enough fertilizer for one thimble-sized dab with each seed. But then the rains, which signal the start of the planting season, did not come. Each day dawned bright and hot. Sunset glowed fiery orange on the nearby Lugulu Hills.

The ground was parched and dry, too hard for the farmers’ simple hand tools. Planting on small African farms is backbreaking work, done by bending over and chipping at the soil with a short tool called a jembe. Precious reserves of food are exchanged to hire a team of oxen. No one uses a tractor.

Timing is everything . Plant too early and seeds will die from lack of water. Plant too late and the soil will be mud. The farmers prayed for guidance. One couple I met, Rasoa Wasike and her husband, Cyrus, wrote prayers on the walls of their house.

Walking into their hut I was greeted by these words in chalk: “With God Everything Is Possible.” That year Rasoa and Cyrus bought a cow in hopes that, as One Acre Fund members they’d be able to feed the cow alongside their family.

The cow would produce milk for extra income. The income would help pay school fees.

At last, in the third week of March, the rains fell. Zipporah Biketi and her husband, Sanet, awoke before dawn, gripped their jembes and began to plant. “Almighty Father,” Sanet prayed, raising his hands toward the glowing eastern horizon, “take control of the planting. Thy will be done.”

Everywhere in Lutacho and Kabuchai, One Acre Fund farmers measured rows with knotted strings, dug holes, carefully added dabs of fertilizer and planted seeds. Then came months of weeding and tending.

It was the wet season, which meant malaria. Leonida, her husband and children were stricken. They scrounged money to pay for medication.

Shoots of corn appeared in fields. The shoots grew, rising higher than the farmers had ever seen. In August I joined Zipporah and Sanet as they awoke early to harvest. “There is no other like God,” sang Zipporah as she and Sanet strode through corn stalks with a machete.

Hack, hack, thump, thump. Ripe ears of corn fell to the ground. The corn was gathered; the husking commenced. I spent days sitting in huts shelling the corn by hand and preparing it to dry.

One morning I sat in Rasoa and Cyrus’s tiny living room. The radio played gospel music. Cyrus sat beneath the chalk words “I love my God.” Together we shelled piles of corncobs. We talked about school, about farming, about prayer.

I looked around. I was in a humble mud-walled hut surrounded by mounds of corn kernels. I had never been happier at work. I had never felt closer to God’s heart for the poor.

I remembered that verse from Matthew: For I was hungry…. At that moment the answer to all my questions about hunger seemed blindingly obvious. God feeds us, I understood, when we help feed each other, when we make sure others have enough.

World food policies must change, yes. But our hearts must change too. We have to recognize that the hungry are among us even if they live far away. God expects us to give our time, our resources and our love until everyone has enough.

That year Rasoa and Cyrus, Zipporah and Sanet, Francis and Mary, and Leonida and Peter grew bumper harvests of corn. They had enough to pay back One Acre Fund for their seeds and fertilizer. Enough to pay for school tuition for their children. Enough to eat through the coming Wanjala.

For Christmas that year Leonida’s family went to church then came home and ate a feast of beans, tomatoes, chicken, beef, bread—and bananas for dessert. “The land of milk and honey,” Peter sighed contentedly.

One Acre Fund now works with 130,000 African farmers, who together produce enough food to feed five times as many people. It’s a drop in the ocean of Africa’s food need. But it’s the beginning of a lasting solution.

For I was hungry and you gave me food. That’s a promise. And a calling.

Download your FREE ebook, A Prayer for Every Need, by Dr. Norman Vincent Peale