Each of us faces pain, no two ways about it. But I firmly believe that in every situation, no matter how difficult, God extends grace greater than the hardship, and strength and peace of mind that can lead us to a place higher than where we were before.

Let me tell you about one of the hardest times in my own life, and how I found this to be true.

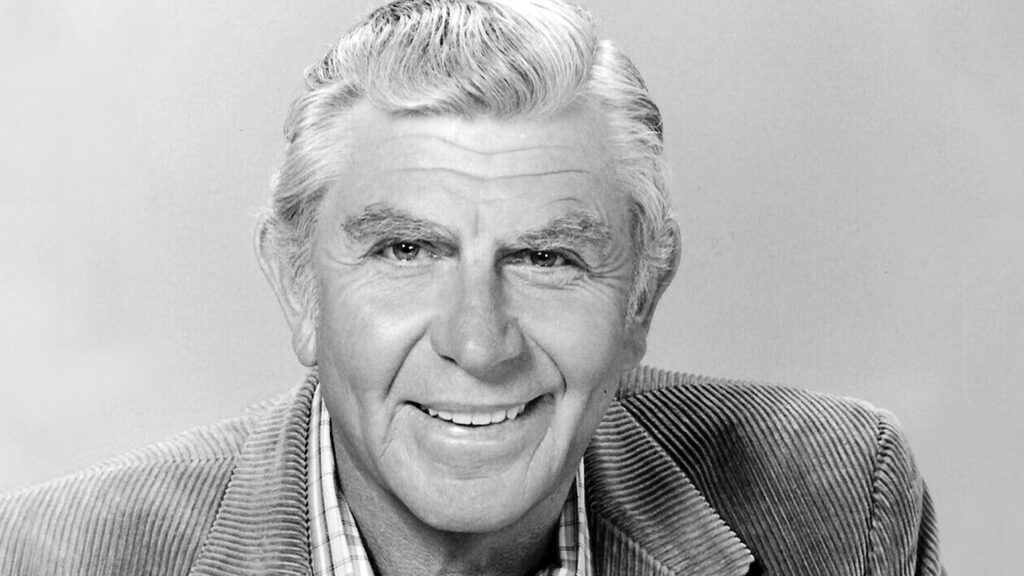

I had been alone for a long time when I met an extraordinary woman named Cindi Knight. She had come to Manteo, N.C., to be in a production of The Lost Colony, a summer play in which I had got my start several decades before.

Our relationship began as a friendship, but as the months passed, I couldn’t help but notice her strong faith and gentle strength. Did I mention she was also quite beautiful? Somehow she fell in love with me. Five years after we met as friends, we became husband and wife.

When she married me in April 1983, I was not at the pinnacle of my career. Ageism is rampant in Hollywood, and although I was only in my fifties, work was getting harder and harder to find.

Cindi had had frequent and major attacks of sore throat all of her life. So, shortly after our marriage we returned to Los Angeles and went to see a throat specialist, Dr. Robert Feder. He determined her sore throats were coming from her tonsils, and scheduled an operation.

Early the next morning we drove over to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center and Dr. Feder took out her tonsils. While she was recuperating, I got a bad case of the flu. Not exactly a honeymoon of the rich and famous.

My illness was strange. As I got better, the symptoms of influenza were replaced by pain–terrible, searing pain that ricocheted through my entire body. Cindi and I joked about our invalid status and settled in that Saturday to watch the Kentucky Derby on television.

But after the race, when I stood up and took a few steps, I pitched headlong into a nightmare. I was overcome by pain so encompassing that I couldn’t feel my feet. I had no control over them, and fell to the floor in agony.

We couldn’t reach any of our doctors that weekend. Yet I was so desperate for relief from the pain that I took some of the codeine prescribed for Cindi for her throat. It barely made a difference.

On Monday my doctor met us at a local hospital. There a roomful of doctors attempted to find out what was wrong. For four days they hadn’t a clue. Finally they did a spinal tap. When the results came in, one mystery was solved.

I had Guillain-Barré syndrome, a rare form of nerve inflammation. It’s thought to be caused by an allergic reaction to a viral infection, such as the flu. The nerves become inflamed and begin to send erroneous and scrambled messages to the brain.

In some people it causes little pain but extensive paralysis; in cases such as mine, it causes little paralysis but intense pain.

There are no drugs or surgery to treat Guillain-Barré–so the doctor sent me home. “There is nothing we can do,” he said. “You’ve got to ride it out. I’ll prescribe some pain medication, but use as little as possible. Come back in a week.”

The following week he said the same thing. And the week after that.

By my next visit I was desperate. If anything, the agony was intensifying. Cindi tried not to let me see her fear, but my physical condition was deteriorating noticeably.

Up to that point we had seen every doctor and specialist I had ever known. Nothing was helping, and the pain had become so consuming that there was nothing else in my life.

Then an old friend, Leonard Rosengarten, a psychiatrist, asked if he could come visit. I didn’t want a friend to see how bad off I was, so I took my most potent pain medication just before he arrived.

A handsome, white-haired fellow, Dr. Rosengarten had nearly died from cancer of the esophagus, so he knew a thing or two about pain. He pulled up a chair and sat … and sat. He waited until the pain medication wore off and I could no longer hide my agony. Then he went to Cindi.

“I know Andy,” he said. “He’s a stoic if there ever was one. So if he says he’s in this much pain, I know he is. Would you mind if I got involved?”

The next morning, true to his word, Dr. Rosengarten got me into Northridge Hospital Medical Center in Northridge, Calif. I was admitted onto an entire floor of people fighting their way back from auto accidents, strokes, Guillain-Barré. Here, the specialty was therapy and pain management.

I’ll never forget that day. The doctor assigned to my case brought along a medication specialist. The first thing the doctor said was, “We know you’re in impossible pain. We’re here to help you through it.”

At those words, Cindi said she saw my body relax. Just to have the severity of my condition acknowledged was the first step on my journey to wellness. The druggist was there to start me on as much medication as I needed, but then I would be weaned off it as I learned to handle the pain in other ways.

The doctors at Northridge Hospital knew that treating pain meant treating the whole person, not just the body. Every day we had classes in biofeedback, which taught us how to use our minds to help control pain.

For example, imagining the pain coursing down through your body and out through your toes actually releases endorphins that physically fight pain. But even though my pain was gradually diminishing, my foot still felt lifeless. It was slow going as I shuffled around.

State of mind is crucial, we were taught. Consequently, we patients were all pulling for one another. I’ll never forget looking into the dayroom one Saturday and seeing a group of stroke patients in a semicircle, with a therapist behind each of them.

The patients were passing a ball from one to another. Each time one successfully maneuvered the ball to the person seated next to him, all the therapists cheered wholeheartedly. There wasn’t a bored or blasé staff member among them.

It was one of the sweetest and most wonderful scenes I had ever seen.

One day the therapist working on me saw one of my toes move. The whole hospital heard about it. Patient after patient and doctor after nurse stopped by my door and said, “We heard the great news! Congratulations!” I was on the mend.

So instead of lying at home, isolated, with nothing to do but dwell on the pain, I was suddenly busy, part of a team, pulling not only for myself but for the others on my floor as well.

By the time I left the hospital a month later, I was taking 85 percent less medication than when I arrived. The pain wasn’t as severe, and I was equipped to handle it.

Although I was no longer in the acute phase of my illness, we weren’t out of the woods yet. It took me nearly a year to recuperate to the point where I could participate in everyday activities. And it was a rough year.

My former manager told Cindi and me that we were virtually broke. We thought life would be easier back in my home state of North Carolina, so we put our Los Angeles house up for sale. But the real estate market was bad, and not one good offer was forthcoming.

As I fought my way back from Guillain-Barré, I never stopped thanking God for the help he had provided me through Dr. Rosengarten, but especially through Cindi. Yet I couldn’t help but feel bad. She had married me for better or worse and all she had got was the worse.

At the end of that year, I sat in our unsold house with no bank account to speak of and no work in sight. Not only was I old by Hollywood standards, but I had also been out of the game for a year. That alone is hard to overcome.

I was getting physically stronger, but I was so depressed. We couldn’t sell the house–I didn’t know what to do.

Then Cindi came up with an off-the-wall idea. “Maybe it’s a good thing we couldn’t sell the house,” she said. “Maybe it was God showing us grace. If we moved to North Carolina now you might indeed never work again. What we need to do is stay here and stoke the fire.”

That day, and every day for quite a while, Cindi and I went over to The William Morris Agency at lunchtime and sat in the lobby. My agent and every agent in the building saw us. Everybody talked to us, invited us to their offices, some to lunch.

The upshot of it was I got roles in four TV movies that year, including Return to Mayberry with Don Knotts and Ron Howard, and the pilot for Matlock–a show that ended up running for nine years!

During this period Cindi decided to give up pursuing her own acting career and work with me on mine. I don’t know how I would have made it without her.

That was more than a decade ago. Now, though Matlock is over, I have a new feature film, and I’ve recorded an album of my favorite gospel songs. Ageism hasn’t left Hollywood, but I hope I’ll continue to work.

Guillain-Barré has left me with permanent pain in both feet, but like an unwelcome guest, it isn’t so bad when I stop paying attention to it.

Challenges and pain will continue all my life, I know, but with Cindi at my side to remind me to accept God’s grace, I’ll go forward and continue to work with love and happiness.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.