Excerpted from The Radical Pursuit of Rest: Escaping the Productivity Trap by John Koessler

As I write this, my attention is divided. I am listening for the chime that tells me I have a new email waiting. When I am at a loss for words, I find it hard to reflect at length about what I should say next. It is so much easier to click away from the screen and log onto Facebook. Or else I scan my favorite newsfeed and check out the latest headlines. To be honest, it’s not news. Not really. It’s gossip mostly. Headlines about actors, musicians and late night talk show hosts. I am not especially interested in their stories. But I keep scrolling, cycling past stories I have read more than once. Hoping all the while that something new and interesting will appear. I am not addicted. I am distracted.

Computer technology has not destroyed my ability to concentrate. But it has made it harder. It has also made rest harder to find. Digital technology has turned our world into one where we are never alone and are always on the job. Most of us don’t think it has any effect on our social and emotional well-being. But the digital world is altering the way we view time and schedule our activities. We use our cellphones to track one another. Wherever we go we are accompanied by the constant murmur of distant friends. Even when we turn off the phone some part of us wonders what we have missed.

Digital culture has also broken down the natural boundaries that used to exist between work and rest. Dr. Kimberly Fisher, a research associate at the Center for Time Use Research at Oxford University, observes, “People don’t have as much mental space to relax in a work-free environment. Even if something’s not urgent, you’re expected to be available to sort it out.” The last thing I do before I go to bed at night is check my email. If I have a new message, it’s usually about my job. If I wake up in the middle of the night, my first instinct is to lean over the nightstand to check for new messages.

The answer to this problem is obvious. All I need to do in order to pursue rest is to disconnect from the digital world. Not permanently but perhaps for a time. It is simple. But it is not easy. The prospect of being unplugged from the grid makes me nervous. This is more than the fear of losing access to information. It is a sense of being detached. I am not a digital native, yet even I feel uncomfortable when I turn off the technology. I feel isolated, cut off not only from the technology but from the relationships it represents.

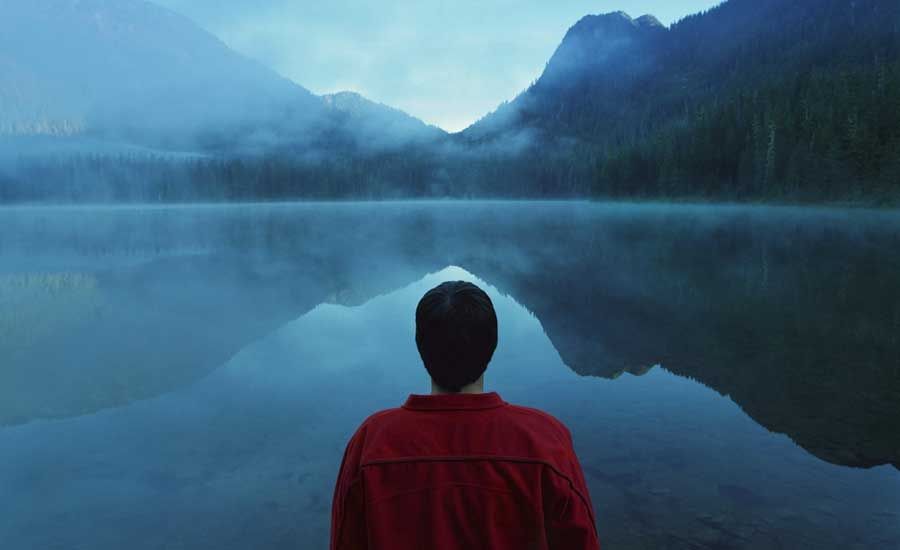

The technology is new but the fear is an old one. It is solitude I dread. And digital culture makes solitude easier to avoid. When Jesus saw that the people planned to make him a king by force, he “withdrew again to a mountain by himself” (Jn 6:15). This was not the first time Jesus did this. Solitude was his regular practice. But I do not quit the crowd so easily. Not only do smartphones, texting and social media enable others to intrude on me at any time and in every location, they greatly increase the likelihood that I will invite such interruptions. I can withdraw to the mountain like Jesus, but I am never really alone. Digital culture is the new background noise. It is the multitude I carry in my pocket. Its incessant chirping intrudes on my most intimate moments and serves as a constant reminder of the waiting crowd. Rest is harder to find in a digital culture because technology has dissolved the two fundamental boundaries that are essential to rest: solitude and silence.

Solitude and Silence

Interruptions were a problem before there was digital technology. Jesus was interrupted too. The crowd intruded on his privacy on more than one occasion. The difference between his experience and ours is that the crowd had to make a serious effort in order to interrupt him. Today they can stay where they are and click their way into our presence. Like Jesus we occasionally need to withdraw from the crowd—especially the virtual crowd. One solution is to turn to habits the church practiced long before the computer age was ever envisioned: the ancient disciplines of solitude and silence.

Solitude is a critical component to our overall spiritual health. Dallas Willard describes the benefit of solitude this way: “The normal course of day-to-day human interactions locks us into patterns of feeling, thought, and action that are geared to a world set against God. Nothing but solitude can allow the development of a freedom from the ingrained behaviors that hinder our integration into God’s order.”

The biblical metaphor for solitude is the wilderness. Moses, David, the prophets, Paul, the disciples and of course Jesus himself all spent time in the wilderness. On the surface, the wilderness seems an unlikely location for rest. After all, the wilderness is not a resort. It is a place of deprivation. While we are in the wilderness we do not have access to our usual conveniences. The wilderness is also a place of disruption. Work must cease and we cannot maintain our ordinary relationships. It is impossible to follow our normal routine there.

This sheds an important light on the experience of rest. We are tempted to think of rest as a kind of indulgence. But in reality the practice of rest often involves a measure of self-denial. Rest requires that we cease our ordinary activities and break away from our daily relationships. When we are at rest we are often unavailable.

When God’s people observed the Sabbath in the wilderness, they could not gather manna. Instead the Lord preserved the extra food they had gathered on the previous day. God’s people were also forbidden from engaging in their ordinary work and were restricted in their movements. But deprivation is not the ultimate goal of rest. The intention was not for the Israelites to go hungry but to recognize that they were being fed by God. They abstained from their normal occupations in order to occupy themselves with something better. Likewise, when we rest in this way we do not cease from all activity; we abstain from one kind of activity in order to engage in another. We deprive ourselves of our ordinary work for a time in order to engage in a higher calling with a better reward. The benefit we receive by leaving our other pursuits behind is that we are refreshed. The ancient command to observe the Sabbath was both a sign and an invitation to enter into the experience of God, who refreshed himself on the seventh day of creation. The pursuit of rest is really the pursuit of God.

—Taken from The Radical Pursuit of Rest by John Koessler. Copyright (c) 2016 by John Koessler. Used by permission of InterVarsity Press, P.O. Box 1400, Downers Grove, IL 60515-1426. www.ivpress.com