Retirement didn't sit well with me. I was used to working hard every day. Truth be told, I was lonesome sometimes. I still had my friend Freeman, though, and we passed lots of time in rocking chairs on my porch, chewing the fat. One day I asked him a question that had been on my mind for some time. "Freeman, why do you suppose I'm still around?"

"Don't know, George," he answered.

"Here I am, 98 years old," I said. "Worked from the time I was four till I was 90. Raised seven children, all of them college graduates. Buried my wife, friends and family. I ought to be just about worn out. But my eyes are good and I've got all my teeth. I get around pretty good, even though folks are always trying to get me to use a cane. And the only doctor I ever saw–which was just a couple years ago–said I had the body of a 60-year-old. Makes me wonder why I'm still here."

Freeman didn't answer. I looked over and saw that my yammering had put him to sleep. I smiled and shook my head, then set to rocking and thinking.

It seemed I'd done everything I'd ever wanted to do in my life, but if I had one regret, it was never learning how to read. I was born in 1898 in Marshall, Texas, the oldest of five kids. Papa couldn't spare me to go to school, so I worked the fields with him till I was 12 years old. But we still weren't doing well enough to feed the family, so Papa got me hired on at a neighbor's farm.

"George," he told me the day I left home, "your great-granddaddy and your granddaddy were both slaves, but they held their heads high. They had the Dawson pride. They passed it down to me, and I've passed it on to you. You're a man now, son. You're as good as anyone else, and don't you forget it."

I wanted to tell him how scared I was, how sad I felt. But something inside wouldn't let me. Instead, I forced myself to hold my head high and say, "Yes, sir, Papa. I'll make you proud."

I climbed into the wagon, Papa clucked to our old mule, and we took off. I waved to Mama and the little ones till they looked like specks standing there in the road. My throat hurt from trying not to cry. But I knew God would take good care of me, like he always had.

I worked at the neighbors' farm till I was 16. Then I had to go back home. My aunt and uncle had died of the fever, and my folks had taken in their nine children. With 16 Dawsons to feed, I took a second job hauling logs at the sawmill.

One day the boss man came up to me and waved a piece of paper. "George, I need you to sign this form," he said. I just stared, ashamed to admit that I couldn't write my own name. Finally he put a pencil in my fingers and guided my hand to make an X. "You're too good a worker to lose." I didn't know what I'd signed, but over time I figured it out. The U.S. had just joined World War I. That paper must have given some reason why I wasn't eligible for military service. I would've been honored to fight for my country. But the Dawson pride kept me from asking what that paper said, and so I spent the war in Marshall.

When I turned 21, Papa asked, "Son, are you ready to be on your own?"

"I reckon so."

"It's time," he told me. "You've worked hard to help the family, and now you deserve to keep the money you earn. Go out and see the world and then come back home and tell us all about it."

I bought a train ticket to Memphis, where I helped build the levees that tamed the mighty Mississippi. I unloaded coconuts on the docks in St. Louis and New Orleans. When I ran short on cash, I rode the rails and lived in hobo camps. For a while I farmed down in Mexico, till a hankering to see snow took me to Canada. Wherever there was work, I took it, stayed as long as I wanted, then hopped a freight to another town.

And everywhere I went, I learned some hard lessons about what happens to a man who can't read. People cheat you out of wages. They sell you a ticket to one city, take your money and hand you a ticket to somewhere else. Up North they'd get mad when you pretended to study the menu and then ordered jambalaya or hominy grits. A man who can't read has to depend on others for information. He has to learn to keep his eyes and ears open, be extra alert. Some of the places I went and the people I met were dangerous, but my common sense took me a long way. And I knew I had the Lord to take care of me.

Come 1928, I'd been wandering for nine years. Mr. Coolidge was our president. We were on the verge of the Great Depression. And me, I was plumb tired. I wanted to find a good woman and settle down. I rode the rails back to Marshall and found my family gone. I wondered why they hadn't let me know. Then again, how would they have found me? Even if they'd known where I was, I wouldn't have been able to read their letter.

I took a job breaking horses and met a woman named Elzenia, who was as sweet as she was pretty. She could read and write, and it made no difference to her when she found out that I couldn't. I wished it didn't make a difference to me. Still, we fell in love, married and moved to Dallas, where I got work fixing roads for the city.

When Amelia, the oldest of our seven children, started school, I took my wife aside. "Elzenia," I said, "I don't want the kids to know I can't read or write."

"You're their daddy," she said. "They love you. It wouldn't matter to them."

"Promise me they'll never find out," I said. "A man's got his pride."

"And you've got more than your share," she answered.

I'd get home from work at night, bone-tired from filling potholes all day. But the smell of Elzenia's stew and the sight of my little ones sitting around our big oak dinner table brought me right back to life. After dinner I'd "help" the kids with their homework, bluffing my way through their lessons by having them read to me. At first, they never knew I couldn't read, though later I think they guessed. But they kept my secret, too. The Dawson pride ran deep.

In 1938, when Mr. Roosevelt was president, I got a job at Oak Farms Dairy, tending the boilers. When the country entered World War II, I was too old to go so I just kept on at the dairy. One day my boss called me in. "George," he said, "no one knows those machines like you do. I'd like to promote you–get some men working under you with you as their supervisor." But my thrill and surprise were cut short when he said, "Fill out this application and we'll get you a new title and a raise."

I looked at that paper in his hand and felt just like I had that day the boss man came to me all those years ago at the sawmill. And once again, I couldn't admit the truth. Instead, I said, "Thank you, sir, but I like what I'm doing."

He looked at me like I was crazy. "Are you sure? This is a great opportunity."

"I'm sure. I want to stay right where I am." I thanked him again and walked out of his office, the old Dawson pride helping me keep my head high.

I did stay right where I was, until not long after President Kennedy got shot. That's when I turned 65 and Oak Farms made me retire. But I didn't stop working. I never could. For the next 25 years, I gardened and did yard work for people nearby. I gave that up when I was nearly 90, when I retired for real. I spent my days fishing and tending my garden. I'd lived a good life, and I was happy, but it still seemed to me like something was missing.

I looked over at my friend Freeman again. He was still asleep. "Lord," I whispered, "you have a reason why I'm still around. Maybe you could let me know?"

I peered down the street. A young fellow was going door to door. He reached my house, walked up to the porch and handed me a piece of paper.

"What's this?" I asked.

"It's information about adult education classes at Lincoln Instructional Center. People can study for their GED, learn math, learn to read and write…."

I didn't hear the rest of what he said. Instead, I felt a warmth deep down inside me. I looked at the young man, then looked at the paper in my hand. I thought of my friends and neighbors and what they might think if they found out I couldn't read. After all these years, my secret would be out. Does that even matter? I wondered. All your life you've wanted to read. Maybe this is why you're still around.

"Hang on a minute while I get my hat!" I said, hopping out of my chair. It was high time for action.

We got into the young man's car and he drove a few blocks to an old building. I knew it well–it was where all my children had gone to school.

I met Carl Henry, the man who would be my instructor. He'd retired from teaching, but like me he didn't cotton to sitting around not working. I peeped into the classroom to get a look at who I would be going to school with the next day. They all looked like babies to me. "Mr. Henry, how old is the oldest student you have?"

"There's a lady in her fifties," he told me. "Most of the rest are in their twenties and thirties."

What would they think of an old man like me puzzling over letters, trying to read and then trying to write? You know what, George? I told myself. The Dawson pride saw you through a lot of tough times. But it's also held you back. Sometimes, it's been a mighty foolish thing.

I mustered up my courage the next day and I went back to the Lincoln Instructional Center. I'd been inside the building so many times before with my children. That old building looked the same, and it smelled the same. But this time it was different. Because this time it was going to be my school.

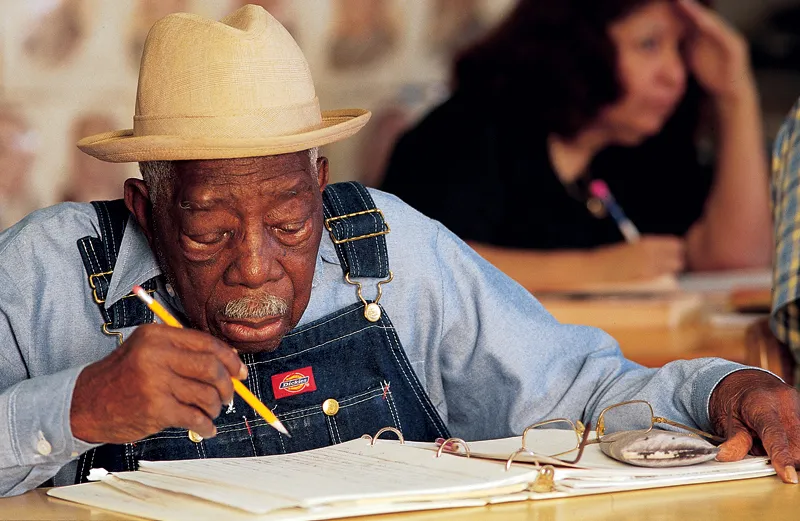

First came learning the alphabet, then words. In three months, I was reading. My first book was called City Life. Not very exciting. Wouldn't even make a good TV show. But I loved it.

I didn't stop there. I'm still going to school, working on getting my GED, even though I'm 103. After all, now I know why I'm here. I'm here to learn. I'm here to help show folks it's never too late, and to tell them that you shouldn't let your pride hold you back.

My favorite book is the Bible. There's a verse I love: "In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God and the Word was God." Now the Word is with me. If there's anything worth being proud of, it's that.

Download your FREE ebook, Rediscover the Power of Positive Thinking, with Norman Vincent Peale