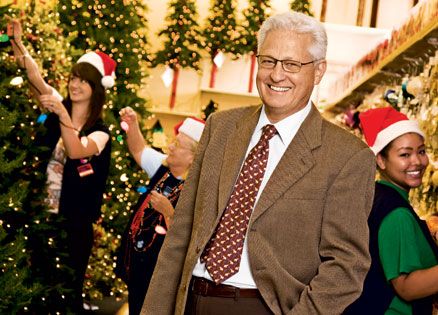

Have you been to Hobby Lobby?

A lot of people come to our stores, especially around the holidays, for arts and crafts supplies, home accents and more.

Our shelves are filled with picture frames, fabric, glue, beads, glitter, clay, ribbon, baskets, candle rings, table runners, wreaths…everything you might need to decorate your house and make gifts for Christmas.

We have more than 430 stores in 35 states, and I’m often asked how the company got started. The quick answer? With a six-hundred-dollar loan and a 300-square-foot retail space.

For the real story, though, I’ve got to go back to the five-and-dime in Altus, Oklahoma, where I found a job–and something more–my junior year of high school.

Altus was a small town when my family moved there in my early teens. There was an Air Force base, a hospital, a post office, a dusty courthouse square with a few stores and churches–including the one my dad pastored.

We lived in a tiny two-bedroom house. My parents got one bedroom, my three sisters got the other and my brothers and I slept on rollaway beds in the kitchen.

To get to the bathroom, we had to walk through Mom and Dad’s room, and it was pretty common to see them kneeling by the bed praying–for an ailing church elder, for a neighbor family struggling to make ends meet. Maybe for our own family, because we were struggling too.

The congregation, all 35 members, did their best to help. They held “poundings,” bringing five-pound bags of flour or sugar or potatoes to worship, anything they could spare to feed our family. Still, there were plenty of times our cupboards were bare.

If company was coming, we would stock the fridge with “leftovers”–we’d put tinfoil over empty cans or plates on top of empty bowls, as if they were full. Folks had enough worries. No need to make them worry about the preacher’s family.

“We’re not poor,” Mom declared. “You’re never poor when you have something to give.” She crocheted doilies and made fried pies and sold them to raise money for missions.

We kids were expected to work too. In the summers we picked cotton. As soon as the girls were old enough, they waited tables or worked in the donut shop.

“Someday I’ll get a job and bring something home for you,” I promised Mom. A new dining room set, I thought, or a sofa that didn’t have stuffing coming out of it.

“Just look for what you can do for the Lord,” she said. The problem was, I didn’t know if there was anything I could do for the Lord.

I couldn’t be a preacher or a missionary or a teacher. Unlike my brother, who was a gifted speaker, I could barely say a word in front of people. I got tongue-tied just giving a book report in English class.

My siblings all got excellent grades and were destined for Bible college. Me, I tried hard, but I wasn’t much of a student. I had to repeat seventh grade. Things didn’t get any easier in high school.

By junior year, I was just looking to sign up for classes where I wouldn’t have to speak. Math was a safe choice; I was pretty good with numbers. Then I noticed something called Distributive Education. “What’s that?” I asked a teacher.

“D.E. is a program that allows students to work for one of the businesses in town. You earn class credit and get paid too.”

Our family could use the extra money. “What kind of job would I get?” I asked.

“Sweeping up or putting away boxes,” he said.

That sounded a lot better than picking cotton. “Sign me up,” I said.

Back then in 1960, the courthouse square was the center of town. My teacher sent me there to McLellan’s five-and-dime. The first thing I noticed when I walked in was the smell of fresh popcorn. It was inviting, almost like someone saying, “Come in and stay a while.”

The next thing I saw was how neat and clean everything was. Not a speck of dust on the counters and wood floors. Altus was in the middle of cotton fields and cattle ranches. In those pre-air-conditioning days it took a lot of dusting and sweeping to keep things spotless.

A short, wiry gray-haired man in a bow tie came up to me. “I understand you’re the young man who’s going to help us out here,” he said. “I’m T. Texas Tyler.” Then he handed me a yarn mop. “You can start with the floors.”

I went over every inch of those wood floors and got to see how well laid out the place was. Candy counter and toiletries in front, sheets and towels further back, pots and pans to the right, hardware supplies to the left.

I lingered in the toy department, admiring the board games and model airplanes on the shelves.

You could buy anything at McLellan’s, and Mr. Tyler made sure you could find just what you were looking for. It made me think of a Bible verse my dad liked to use in his sermons, “Whatever your hand finds to do, do it with all your might.”

Maybe I was no good at schoolwork, but I would give this job my all.

Mr. Tyler was an excellent teacher, and his subject was retailing. He was constantly finding something new for me to do. He sent me to the stockroom where I took boxes off the conveyor belt and put price stickers on the merchandise. Another time he had me reorganize the shelves.

“There’s a place for everything, son,” he said, “and your job is to make sure everything’s in its place.” I knew what he meant. At home I had only one drawer for all my things.

One day Mr. Tyler asked me to roast a huge supply of nuts. He had separate sacks of peanuts, hazelnuts, cashews and walnuts that needed to be salted and roasted together. “Why don’t we just sell them like they are?” I asked.

“Think of our customers,” he said. One of our biggest was the Officers Club at the Air Force base outside of town. “When the Officers Club has a party, they want the nuts roasted and mixed already, and they’re willing to pay for that convenience.”

Think of the customers. That sounded just like what my parents instilled in me about serving others, putting their needs first.

No task was too lowly for Mr. Tyler. One day, he asked me to clean the toilets. I dumped some cleanser in, swirled the brush around and called it a day. Mr. Tyler called me back, pointing out how much grime I’d missed. He got down on his knees and scrubbed the toilets till they sparkled.

It was a brilliant example of what my dad called servant leadership–no job, however humble, is beneath the boss. To lead well you need to serve.

I had my share of successes and blunders too. Like the Easter display of chocolate bunnies for our front windows. It looked great when I set it up in the evening, but the next day in the hot sun, the bunnies melted into a pool of chocolate.

“We all make mistakes,” Mr. Tyler said. “The important thing is to learn from them.”

By senior year I was putting in almost 40 hours a week at McLellan’s. I added to Mom’s fund for mission projects. I was able to buy her a dining room set, a new sofa and a refrigerator. More important, I discovered what I could do for the Lord–work at the calling he had given me with all my might.

Really, I founded Hobby Lobby on those principles I learned at McLellan’s five-and-dime: Always think of the customer. Put people first. Don’t get stuck behind a desk (Mr. Tyler didn’t). And find a way to do what you do for the Lord.

One way we do that at Hobby Lobby is by closing our stores on Sundays. Weekends are big in retailing, and I’m told we lose millions of dollars because of this, but I wouldn’t change it for the world.

Our employees are able to spend Sundays at home and at worship with their families, and that’s more important to me.

I know Mom and Dad would be pleased. So would Mr. Tyler. What they taught me has become the Hobby Lobby way.

Did you enjoy this story? Subscribe to Guideposts magazine.