We called it Black Thursday.

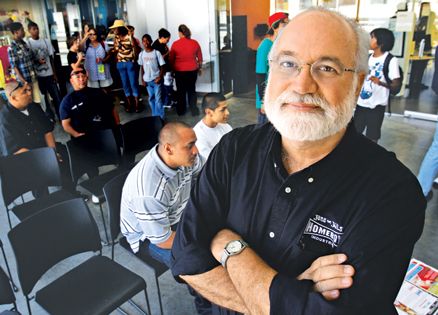

A group of us gathered in my office on a warm spring morning last year at Homeboy Industries, a gang-intervention program started nearly two decades ago in a tiny East Los Angeles church.

Crowding the walls was evidence of our work—photos of gang members who’d turned their lives around, drawings and paintings by kids from the projects, even a proclamation from one of East L.A.’s most notorious street gangs thanking us for our “efforts to make our lives and our community better.” Outside my office we saw gang members coming off the street for job training, counseling, maybe to apply to work in the bakery and café we run, or to have their tattoos removed by volunteer doctors.

The street was desolate, a neglected corner next to a bus storage depot less than half a mile from the Los Angeles Men’s Central Jail. Inside, though, everything hummed with life, with prayers and warm greetings, sometimes with tears of joy.

Except today we were meeting to practically shut the whole operation down. The recession had hit hard and much of our funding had dried up. We’d cobbled together the payroll money for the past few months but now the well was dry. We had more than 300 employees, most of them former gang members, counseling addicts, answering phones and teaching classes. They’d all have to go. The senior staff would be laid off. I would be laid off, and I’d helped found the place. We talked all morning about what to do.

We were desperate for another solution but there seemed to be only one course of action.

Finally we stopped for lunch. “We’ll break the bad news this afternoon,” I said. Silently I gave one last frantic prayer for help.

When I returned, word had already spread. The parking lot, sidewalk and lobby were mobbed. Huge guys covered in tattoos were sobbing. Homeboy Industries is the largest gang-intervention program in the country and the only operation of its kind in Los Angeles, America’s gang capital. For these guys it was a lifeline. And I was taking it away.

Worse, I blamed myself. We’d recently built a new headquarters that let us bring all of our programs under one roof. It was paid for but I hadn’t anticipated the increase in costs our expansion would generate. The number of gang members, or “homies,” as they call themselves, coming to us had quadrupled to 12,000 per year. (There are an estimated 100,000 gang members in the L.A. area.) I walked through that swarm of homies in a miserable daze.

I thought about all the kids who’d come to us over the years broken down and brokenhearted. That’s the real reason kids join gangs. They’re not natural-born criminals. They’re just out of options—no jobs in sight, dysfunctional schools and families, no sense of belonging in society. Yet these kids had taught me so much—more, it sometimes seemed, than I’d ever taught them.

I remembered one year in particular, when I was as depressed and anxious as I was that Black Thursday afternoon. It was 1992, six years after I’d been assigned as pastor of Delores Mission Church in East Los Angeles. Delores Mission was the poorest parish in all of L.A., basically two sprawling public-housing projects right next door to each other. The projects were home to eight different warring gangs.

Even though I was a middle-class white guy who spoke little Spanish, dealing with those gangs became a major part of my ministry. Mothers and grandmothers in my parish were distraught at the constant shootings, stabbings and drug dealing going on every day right outside their doors. They hated the violence but they loved their children. Maybe, they reasoned, if we made our church a place of love and refuge and helped these kids find jobs and mentors they’d leave the gang life. By fits and starts we put together a program that placed kids in local jobs and taught them basic life skills. We even bought them suits for interviews. We started our own businesses and we hired homies to run them.

I wasn’t smart enough to let it all take its own time. Instead I tried to solve the gang problem single-handedly. I never slept. Late at night I’d get on my bicycle and pedal through the projects. If I saw homies with guns drawn I confronted them. I escorted kids to their doors. I pleaded with gang members to leave the life and come to us for counseling. I shooed away drug dealers and even tried to broker truces between rival gangs. The truces were worse than useless. Gangs never fight about anything real. It’s all turf and posturing and desperate efforts to mask despair and fear.

As a Jesuit I was mandated to take a long retreat that year. I spent 30 days in silent prayer and realized that all of my efforts had come to little. The housing projects were more torn up by violence than ever. I was burned out. I returned wondering if I’d ever find a way to make a difference.

That’s when I met Pedro, a young guy addicted to crack. Every time I saw him in the projects I offered to get him into rehab. “I’m okay, G,” he’d say and slink off. (The homies call me “Father G” or just “G.”) One day, to my total surprise, Pedro said yes.

I drove him to a rehab center north of L.A. A month later his younger brother, Jovan, also a gang member, committed suicide. I picked Pedro up from rehab for the funeral. I had no idea what to say but Pedro launched into conversation the minute he got in the car. “It’s a trip, G,” he said. “I had this dream last night and you were in it.”

Pedro said he and I were standing in a large, empty, pitch-black room when suddenly I lifted up a flashlight and turned it on, illuminating a light switch on the wall. I didn’t speak, didn’t move, just held the beam steady. “All of a sudden,” said Pedro, “I realized I was the only one who could flip that switch. You couldn’t do it. I had to do it. So I walked over there and I took a breath and I flipped it on. And the room got light.” He paused and I saw he was crying. “And, G,” he choked out, “I realized that the light…is better…than the darkness.”

That was all. We didn’t say much more. After the funeral Pedro returned to rehab. His story, though, flipped a switch in my own mind. I realized what I’d been doing wrong—I’d been going around trying to turn on lights for everyone in the projects when in fact all I could do was aim the flashlight. I couldn’t save those kids. Only God could save them. My job was simply to point the way.

My work changed after that. No more bike patrols. No more brokering truces. I focused more on Homeboy Industries and made it clear to kids that I was ready to work with them only when they were ready to work with us. We sometimes joke that our motto (“Nothing stops a bullet like a job”) should be changed to “You just can’t disappoint us enough.” But that doesn’t mean we let kids off the hook. If they slack off or drift back into the life, we send them packing. We pray hard they’ll come back. But in the end that’s their decision.

The day after the layoffs I arrived at the office to find the place as noisy and busy as ever. “We’re still working,” the staff told me. “Maybe you’ll be able to pay us someday.” Pretty much everyone showed up, including Pedro, who’s a case manager.

Homies went to Dodger Stadium to collect donations from fans lining up for games. They took to the streets to sell copies of a book I’d recently written. They called newspapers and television stations and soon the place was swarming with reporters. “Your terrific press person, Melissa, called us,” a television cameraman told me. He meant a homegirl who works in the tattoo-removal clinic and had never spoken to the media before in her life.

Donations trickled in, then snowballed. In a few months we’d raised $3.5 million. Los Angeles County gave us $1.3 million to serve kids on probation. It’s still not enough. Our businesses, staffed almost entirely by homies, are self-sustaining. But the rest of what we do is slow, expensive work. So far we’ve managed to put about a hundred people back on the payroll.

I have no idea what we’ll do come June, when the county contract runs out. Still, I don’t despair. God brought us this far and he’ll carry us along. I may be shining the flashlight and the homies may be flipping the switch. But it’s God who provides the illumination. On Black Thursday and every day.

Download your FREE ebook, A Prayer for Every Need, by Norman Vincent Peale.