How to help someone in the midst of grief? How to pray for them?

I think of myself as a young Boomer, but somehow I’ve hit that age where friends, my contemporaries, are dying. Last summer I went to the funeral for the husband of my wife’s college roommate. On Sunday at church, I hugged a friend, another Boomer, whose husband died very suddenly. At a dinner last week, I sat next to a woman whose spouse has a terminal illness.

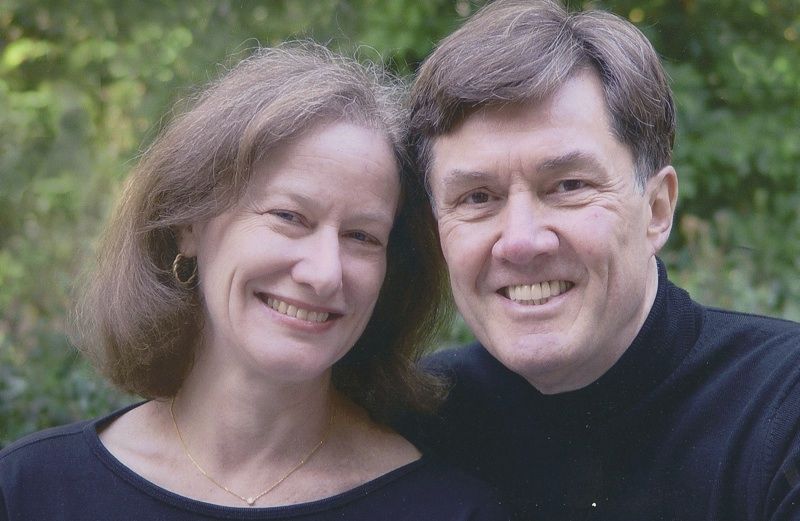

How can I help these friends? What comfort? Recently a college classmate of mine, Jill Smolowe, sent me a copy of her new book, Four Funerals and a Wedding, in which she describes in heartbreaking detail the long illness and death of her husband, Joe Treen. And then other family deaths at the same time.

“That sounds like a depressing book,” a colleague said, seeing the copy on my desk.

“No, it isn’t. It isn’t at all,” I responded, because Jill is not only a fabulous writer–a longtime editor at People magazine–but she discovers in the midst of her sorrow, her insuperable losses, that she has enormous reserves of strength. She’d suffered terrible bouts of depression in the past, but grief was not like this. As she writes:

Yes, I experienced moments when I felt choked by sorrow, hollowed by loneliness, overwhelmed by Joe’s absence. But they were–and three years on, still are–just that: moments. To my surprise, my feelings of devastation were intermittent, not all-consuming; disorienting, not unhinging. Grief, for me, was neither the unremitting quagmire of despair I’d experienced twice with depression, nor the total shattering I’d encountered in memoirs, novels and films.

She would have bouts of tears that she gave into, sobbing, pounding the floor with her fists, emptying boxes of Kleenex, but they rarely lasted more than 20 minutes. “I disappear through a hole at the center of the earth,” she wrote in her journal. “Then I resurface and go on.”

It’s the resurfacing that is so stunning, remarkable, the strength of the human spirit and our own God-given capabilities. Jill was glad of work, glad of the notes to write, the details to take care of. But photos of Joe in the house were so painful that she would avert her gaze. As she says, bereavement would convert a cherished memory into a source of pain. And yet, and yet.

What I didn’t expect was that the feeling of extreme pain would be attended by feelings of extreme gratitude. Even stronger than the appreciation I’d experienced during Joe’s illness, this torrent of thankfulness registered people’s kindness with a hyperalertness. Deeply, intensely, I felt appreciation for what remained good in my life.

Hearing about grief from the inside gives me a better notion of how to respond to it. Jill recognizes that sometimes people were embarrassed, didn’t know what to say, avoided mentioning Joe altogether, as though he had never lived. She was so grateful to people who could be direct with her. Not sentimental, not vague, specific, aware, directly supportive. Especially helpful were words from those who had experienced loss.

Of course, I always pray for the grieving. Now I feel like I know where to direct my prayers.

P.S. I don’t want to spoil everything by explaining the wedding in the title. Suffice it to say, Jill has also had cause to rejoice in the years since Joe’s death.

Photo: Jill Smolowe and Joe Treen