In the summer of 1976 I flew out to the Philippines to begin work on a film that, to my way of thinking, was a great step upward in my career.

I had a leading role in Apocalypse Now. At last—a really important movie for this boy from Dayton, Ohio. From now on it was going to be big parts and a taste of real fame. How was I to know it would nearly be the end of me?

From its inception, Apocalypse had all the earmarks of success: Francis Ford Coppola, with his worldwide recognition and glittering record of box-office hits, was at the helm as director, Marlon Brando was the costar, Robert Duvall had a supporting role, and the film’s financial budget was way up in the millions of dollars.

I had been assigned the role of Captain Ben Willard, an Army intelligence officer and hit man, who, although on the brink of emotional and psychological collapse, had been ordered by his superiors to travel through war-torn Vietnam into Cambodia, where he was to assassinate an American Green Beret colonel. That colonel, played by Marlon Brando, had, from all appearances, gone mad and was operating his own private renegade and bloodthirsty armies in the wilds of the Cambodian jungles.

Just before the filming of Apocalypse began, Janet, my wife of 15 years, and our four children joined me in the Philippines, where movie set designers had transformed the lush, green tropical vegetation outside Manila into amazingly close replicas of all the actual photographs I had ever seen of Vietnam and Cambodia.

For as long as I can remember, I have always taken my wife and family along to live with me during extended periods of time on location. I had never wanted my acting role to get in the way of my being a good husband and father. This time was to be no different.

From the first moment I read the script of Apocalypse, I was fascinated by the character of Captain Willard. I generally try to create a character I’m portraying in my own image. In “becoming” Willard I had no idea how dangerous this would be, for Willard was emotionally burnt out, insensitive to those around him, uncaring, hard-drinking, overly ambitious, self-centered and single-purposed. Were these menacing attributes of this on-camera character, coupled with the intensity of my own pursuit of success, beginning to boil over into my off-camera life? Or was I really more Willard than I wanted to admit?

Janet tried to talk out the wrinkles growing in our relationship and tell me what I was doing to others around me, but I vehemently denied that anything was changing—least of all me. Then Janet tried to reason with me that she and the kids didn’t mind making some sacrifices for my success, but now this role, this Willard thing, was making me lock them out. I was making them more and more miserable. Even Francis Coppola was beginning to find me difficult to deal with, but I couldn’t seem to help myself.

Although I was raised in a devout Catholic home, the thought of praying about my family problems never entered my mind. And I wasn’t about to go near a church—I had given that up in my mid-20s.

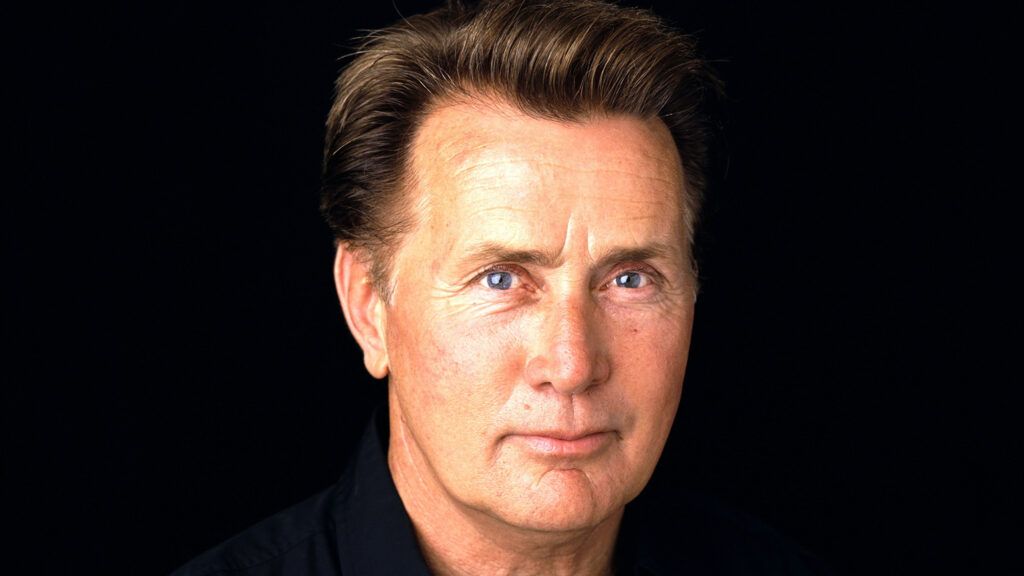

To understand where all this was taking me, let me explain where and how it all began. First, Martin Sheen is only my acting name. Born and christened Ramon Estevez 45 years ago, I was the seventh of 13 children of Francisco Estevez and Mary Ann Phelan Estevez. My father, a Spaniard, met my mother, an immigrant from Ireland, while the two attended citizenship training classes in Dayton, Ohio.

I was 11 years old when my mother died. My father, a factory worker for the National Cash Register Company, never remarried, and single-handedly raised us (ten boys and one girl; two boys died in infancy) in a lower-middle-class neighborhood in Dayton. I attended Holy Trinity grade school, run by the Sisters of Notre Dame, and Chaminade, a Catholic high school for boys. Early on I served in the parish church as an acolyte. It was our life in the church that helped keep our family together.

By the time I was six or seven years old, I was spending hours alone acting out the parts of characters I read about in books. Not until movies came into my young life did I know that what I was doing had a name—acting—and I knew then that I was an actor. Right after high school I headed for New York to fulfill my dream of becoming a professional actor.

That’s where “Martin Sheen” was born. The first name came from Robert Dale Martin, a drama coach and friend in New York. The last name came courtesy of the late radio-TV personality Bishop Fulton J. Sheen, whom I admired and—because of my name change—met in 1965. Martin Sheen. The name sounded good, solid, Irish. To my 18-year-old mind, Ramon Estevez was too ethnic and would cause me to get typecast.

My career in New York grew gradually, first on the stage, then TV and films. I married Janet, an art student at the New School for Social Research, and our family grew gradually too—three sons, Emilio, Ramon and Carlos (Charlie), and finally our daughter, Renée, all two years apart.

When the Captain Willard role in Apocalypse Now came along, it seemed to be the one big bright opportunity I had been waiting for. But the grueling work of putting together Apocalypse went on and on, often in hot, steamy days and sultry, humid nights. After nearly six months into the shooting, my Willard-born attitudes, with all the damage they were doing to my family life, had not changed. Our home was now a hotbed of intense stress and pressure.

Our kids began begging to go back to the United States to live with relatives. And finally Janet gave in and let them go. Then one day in early March 1977 Janet went into Manila for an overnight stay to make sure we would have a decent hotel when I came the next day for a weekend there.

Late in the evening I got back to the large rustic cabin we had rented for the duration of the filming. It was a comfortable place, perched on a mountainside and overlooking a volcanic lake. However, like all the other houses in the area, it had no telephone, radio or TV.

On that March night, I was alone and tired. Shooting the scenes of that day had drained me physically and emotionally. I looked forward to sacking out for the night, but when I went to bed I couldn’t sleep.

I lay in bed for a while, then got up and paced wildly around the bedroom floor. I felt strangely clumsy and awkward, and at times it was hard to keep my balance. My breathing grew strained. When I went back to bed, sleep defiantly refused to come. I don’t recall how many hours I continued in this state, but it must have been about three in the morning that I began to sweat profusely. A nagging pain crept into my right arm, and I leaped out of bed again. Something was terribly wrong, but I had no idea what.

I started to feel faint and slumped to the floor. Then came a devastating explosion of pain in my chest. It left me too weak to stand up. My breathing became rapid and difficult, I had to get outside for help, even though I was aware that outside a windstorm was raging.

I slithered slowly over to the closet and, one by one, yanked down pieces of clothing, then twisted and pulled my way into them as best I could. Another blast of pain hit my chest, and I knew what was wrong—a heart attack, the same thing that had claimed the lives of my mother, father and two of my older brothers. I knew I was dying.

I began to crawl slowly, agonizingly toward the door. The pain in my arm and chest was making me weak. Sweat poured off my body. I rose awkwardly to my feet and began taking baby steps out the front door. Just outside the house another blast of pain knocked me to the ground.

The wind was still howling. Towering palm trees were bending near the ground and lightning flittered nervously about the sky, giving the whole area the look of an eerie movie set. But this time it was definitely not a movie. Ramon Estevez/Martin Sheen was dying, and the scene was all too real.

Once more I struggled to my feet, only to find that my depth perception was failing. I reached for trees and clumps of shrubbery, only to find that they were about 50 feet away. Then my eyesight went altogether. I yelled weakly for the guards the production company had provided, tripped over something and fell again. My hearing was also weak, but I could feel the wind pick up speed. I couldn’t move anymore. That’s when I called to God for help.

I don’t know how long I lay there before one of the security guards making his rounds spotted me and carried me to the guardhouse station. He laid flat boards across the back of a Jeep and gently placed me on them. Then he drove a bumpy mile and a half down the mountainside to a small village, where a young Filipino doctor had a small clinic. I had come to know the doctor earlier since he had often given first aid and other medical treatment to members of the cast and crew.

He found my heart rate was very low and my blood pressure way up. He slipped a glycerin tablet under my tongue. Soon another blur of a figure bent over me. It was a priest. “Do you want to make your confession?” he asked in broken English. I tried to answer but couldn’t. He waited a long moment, then began to intone the Roman Catholic last rites.

My last recollection before losing consciousness was of being placed aboard one of the helicopters used as a prop in Apocalypse for a daring flight through the storm to a hospital in Manila.

When I awoke, another blur of a figure was bending closely over me. This one was smiling. Janet.

“You’re going to make it, Babe,” she said glowingly, “and remember, it’s only a movie. It’s only a movie.” At that very moment, all that ailed me physically, emotionally and spiritually began to heal.

Even though I did not physically die that night, the Willard character in me did. My face-to-face confrontation with death and my own human vulnerability purged the need to be an empty celluloid image bent on the accumulation of such things as fame or wealth. I had been shocked into recalling something I had known all along but had forgotten: that love is the true foundation of happiness. Love of family, love of people, love of God.

In the years since that painful night, Janet, our children and I have grown closer and happier than ever. I have long since returned to my church. I have never forgotten that even though I turned my back on God, in my time of greatest need, he came to find me.

For more inspiring stories, subscribe to Guideposts magazine.